By Jill Mapes

Pitchfork | November 20, 2023

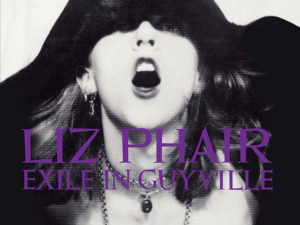

Right now, Liz Phair is in a good place with Exile in Guyville, her 1993 debut that catapulted her to the center of alternative music. “To have it still resonate in the culture is a mixed blessing,” she tells me one afternoon, calling from her home in L.A. “Sometimes we’re getting along, sometimes we’re not. But these days we’re like those couples who have been together a long time and we just really appreciate each other.”

Earlier this month, the 56-year-old kicked off a tour performing the classic album in its entirety, a brief but meaningful run of shows that she says could be the last time she presents the record as a full “immersive experience.” That’s not to say it’ll be the last time Phair mines the Guyville era for material—her forthcoming second memoir, Fairy Tales, will have her revisiting that time in her life, too.

Three decades later, Guyville has never stopped being relevant as a rejection of indie rock beta-male fuckery, but also as an affirmation of something bigger: embodied female sexuality and a hard-won sense of autonomy. “Flower,” my personal favorite track, remains a shocking song about desire in part because of how simple and viscerally spoken it is: “I want to fuck you like a dog/I’ll take you home and make you like it,” Phair sing-speaks over sparse chords and her own girlish backing vocals. “That song ripped a hole in my universe,” she says now, adding that it made her preppy and proper family very uncomfortable.

But such slights don’t get to Phair the way they used to. Maybe it’s the benefit of age, of having cycled through different musical lives and arriving, most recently with 2021’s Soberish, back in the company of her Guyville collaborator Brad Wood, more self-possessed than ever. Or maybe it’s just accepting that reaching a new phase of life is always going to require some adjustments. “As you come up to your next evolution, it gets really intense and unacceptable ’cause you’re resisting going through this scary thing,” she says. “It’s like in a tsunami where all the houses clump up against the poles. All of your life is getting compacted ’cause you won’t go through. But you have to go through.”

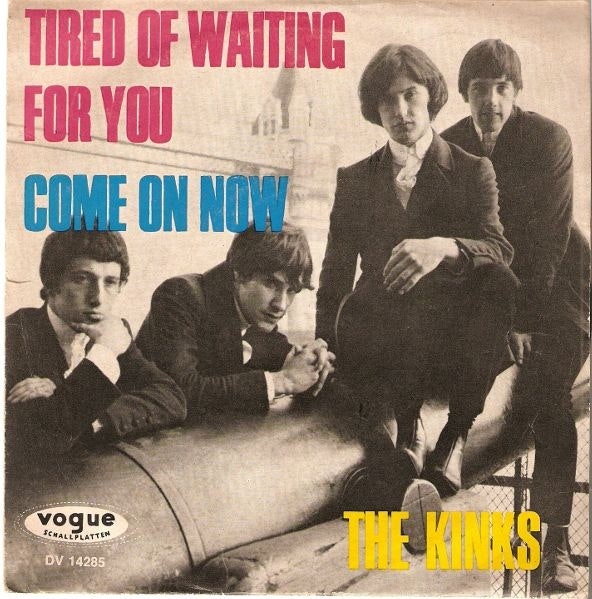

The Kinks — “Tired of Waiting for You”

But such slights don’t get to Phair the way they used to. Maybe it’s the benefit of age, of having cycled through different musical lives and arriving, most recently with 2021’s Soberish, back in the company of her Guyville collaborator Brad Wood, more self-possessed than ever. Or maybe it’s just accepting that reaching a new phase of life is always going to require some adjustments. “As you come up to your next evolution, it gets really intense and unacceptable ’cause you’re resisting going through this scary thing,” she says. “It’s like in a tsunami where all the houses clump up against the poles. All of your life is getting compacted ’cause you won’t go through. But you have to go through.”

To me, it was always about the words too, because I wanted to know what these stories were. I was reading Aesop’s fables at the time, and there was a story of a fox that got his tail caught in a trap and then tried to convince all the other foxes that having no tail was the chic way to go. I somehow conflated “Tired of Waiting for You” with this fox that’s in a trap, and that was the beginning of my music career. I was like, “I’m gonna think about this story and figure out what the hell is going on,” and ever after, that’s what I do to all music. I go through the window and enter that dimension and I’m there, full of suspension of disbelief, trying to figure it out.

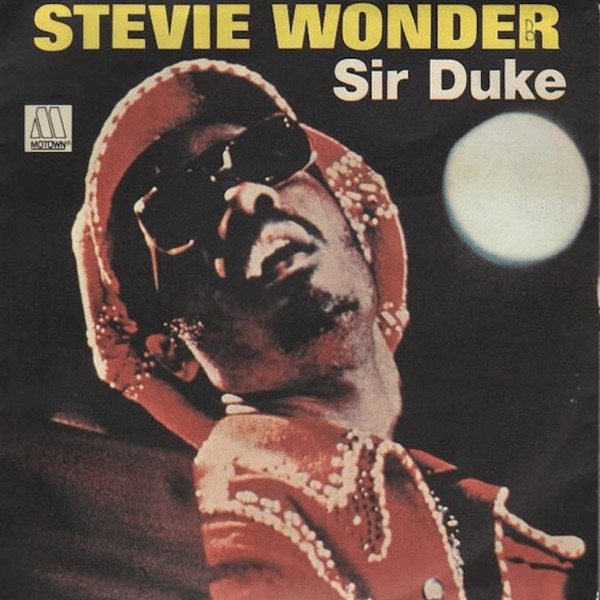

Stevie Wonder — “Sir Duke”

My parents took us everywhere as children—parties, restaurants. We had to be on our good behavior all the time. But we got exposed to a great deal at a young age, like Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life. I was hearing it all the time, everywhere. And “Sir Duke” is really important to me.

My dad and I bonded over “Sir Duke” because, in the lyrics, Stevie is talking about all these great musicians from the past who were sort of from my dad’s era. Like before he met my mom, when he was at Yale and going off to New York with his friends—they went to clubs and saw music. They were probably the only white people there. I just remember really digging it with my dad and getting a feeling that I knew a little part of him that the rest of us didn’t share. It was cool to picture him in a life before us. He liked that I liked that song.

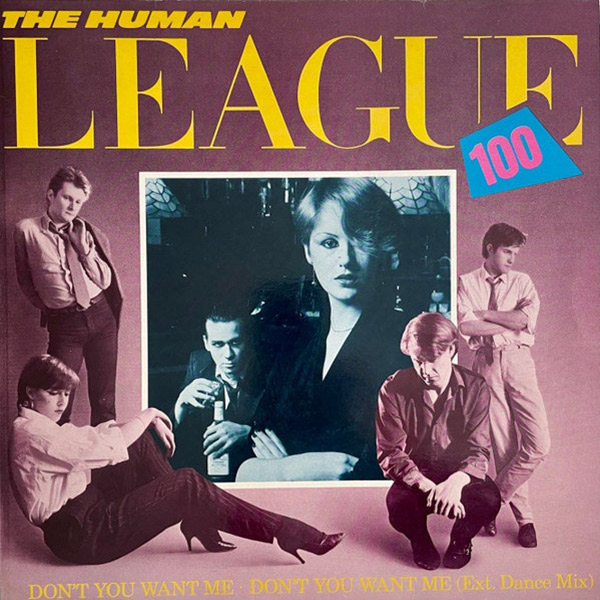

The Human League — “Don’t You Want Me?”

This is when I suddenly get pretty, after glasses and braces. I have my figure finally. Because I immediately got super chubby right at puberty, my mom was like, “You should run.” So there I was running cross country, looking pretty good, and everything was happening. At the peak of this newfound womanliness, I went on this big trip that my summer camp offered, where I went paddling up in Quetico Park, in the boundary waters above Minnesota. So a bunch of girls and I were up in the middle of nowhere—we could have easily died. I remember carrying my canoe on my shoulders to cross the land in between all these little finger lakes, and it was just mosquitoes all the way up and down my arms, so many that we stopped getting welts.

Anyway, we would scream this Human League song to the boats: [sings angrily] “I was working as a waitress in a cocktail bar.” Like: This is nature. No, this is Human League. As much as “Don’t You Want Me” was just the song of the summer and no big deal, it also became really formative for me, because it was the first time I had heard a woman clapping back in a song. Until that point I had always wondered [about the female perspective] in these stories. I would identify with the girl that they were singing about in my little romantic mind, like Cecilia—yeah, I did get up out of the bed, Paul Simon. But this was the first time that I really heard a woman say, No, no, no, let me set the record straight. That became my thing. And it all started with this stupid song. Guyville wouldn’t be Guyville without the Human League.

Sonic Youth — “Schizophrenia”

It’s the late ’80s, and I have left the suburbs. I have left my bouncy, flunky hair and my frosted lipstick behind. Basically, I inverted myself: I became the opposite of everything that I was before. If I had been a bright and sunny blue-eyed blonde, I was suddenly pale and angry, my hair was lank and maybe not washed. Where I had worn super figure-hugging clothes and been ultra-cute at all times, I now bought second-hand thrift store stuff that was baggy and I wasn’t wearing a bra.

I think it partly has to do with the pressures that I felt in high school. My brother was going through a lot of problems, and watching him struggle was traumatizing for me. And then just the way guys always treated me, like, in terms of trying to sleep with you. I was a virgin until I went to college, which I know is shocking because of “Fuck and Run,” but I wasn’t untouched. I knew exactly what that rejection was, what being used was.

There was this huge disparity between what girls were raised to want and what the world was offering us. It almost seemed like we’d been lied to—completely infantilized. I remember going up to the radio station at Oberlin College—I was dating someone who was a DJ at the time—and seeing the Sister album cover and hearing that music. It was my gateway drug into alternative. I went to Cleveland to see Sonic Youth play and shoved myself right up to the front. I was feet away from Kim Gordon, and she was the epitome of self-possession. She was both incredibly tough but also incredibly fragile. And I saw this new way of being feminine within an attitude that made me feel safer out in the world.

I had a toughness about me after that, and it worked better for me. I wasn’t looking for a white-collar job. I wasn’t gonna do what I had been raised to do. I decided to pursue my essence. I had grown up with tons of music—my parents had taken me to the symphony, to the theater, all of it—but Sonic Youth was the first time that I saw ugly sounds made gorgeous. And that you could wear your ugliness. You didn’t have to hide it. That clicked for me with the song “Schizophrenia.” I had no idea how much of myself I had repressed, how my ugliness was unacceptable in the world that I’d come from. This was offering me an entirely new paradigm: Ugliness was the beauty.

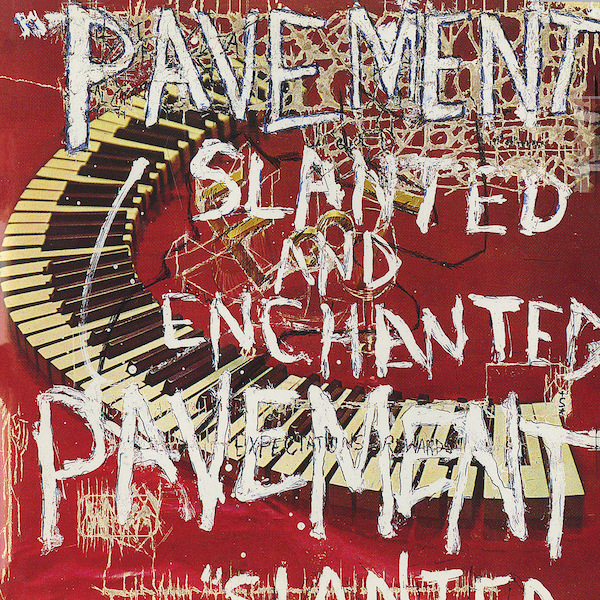

Pavement — “Trigger Cut/Wounded Kite at :17”

I really was never, ever more on my own than at 25, alone in Chicago hanging out at the bars, trying to make Guyville in fits and starts. I had no money at that point, I was fully committed to the artistic life. Here’s what no one got about me: I came from an entirely different world. You can’t imagine how preppy my world was. It was nothing like the indie rock world. The two groups did not get along, and still don’t. My parents gave me a really good life, and they could not understand why I would throw it back. But it’s my life, and I had no choice but to find a way to integrate. It’s taken decades. I still feel like I’m about 10 years off from integrating my entire self. But that’s meaningful work in a life, and I don’t think a lot of people in music value that.

Meeting people from [New York indie label] Matador, suddenly I was with people that had been on a similar path. I felt like Matador was a home for people that had fled these kinds of upbringings, who were taking themselves seriously as artists when no one else would. I really felt like I had a home there. They got me a lot better than the people in Chicago ever did.

Pavement’s Slanted and Enchanted was on repeat on my Walkman at this time. It was what I took to give me the bravery to do everything I was doing: I was gonna make Guyville and show the boys. I’d been the girlfriend of musicians, I’d been the person in the room listening to all these men argue, and if I ever offered to put a song on, I was told how stupid and awful it was. But I never believed them. They were not going to intimidate me, even though it totally did.

Pavement—especially “Trigger Cut/Wounded Kite at :17,” whatever the hell that title means—felt like they were taking a traditional song structure and blowing it up and then putting it back together with all the notes wrong. Slanted and Enchanted felt like someone doing what I had inside my heart to do, and it was my war call. I didn’t want to become Pavement though—I wanted to be the Liz Phair of Pavement.

Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds — “Into My Arms”

I’m married at this point. The experience with Guyville was kind of traumatic for me—all those indie people had to be like, “Oh, now she’s the indie rock queen.” So of course my need for balance and being grounded kicked in, and I swung all the way back to the suburbs. Suddenly I wanna get married, I wanna buy a house, I wanna have kids. Like, I’m done. I quit. And thank God I had [my son] Nick, because it was giving birth that brought me back to wanting to do music again. It’s like: Are you serious? You don’t want a job where you make music and people clap? That’s a really good job.

Nick Cave had always seemed larger than life to me. He was cooler than the indie people I knew. He was taller and more striking and had more presence and just more chops. “Into My Arms” was so poignant, mature, valid—it was a true ballad that my parents would like. It touched that part of music that no indie or mainstream pop can touch. It’s sacred. And it reminded me that I had started singing in the choir at church. I had this renewed appreciation for singing.

Some of this stuff does come from a mysterious place. It lands in your lap as a songwriter, and you feel incredibly, profoundly grateful to be holding this thing you just made. Like, how did I do that? Where did that come from? It feels so good to sing it. All of that came back to me.

Missy Elliott — “Work It”

In the early 2000s, I saw Missy as this new titan, like someone who was gonna start a production house and produce other people’s work. It was just that actualization of herself. “Work It” was overtly embracing her pleasure, and I completely related to that. Even though women have been sex objects for the last 20,000 years, if we step into the role of the subject, people lose their minds and can’t handle it. But how can anyone find anything controversial about this song? It’s such a perfect example of women being shocking when they do what men did decades before, and yet she’s doing it in this totally new way.

I didn’t stop listening to that song for months. She was the light in the front of my boat as I was going through a scary, dark swamp, career-wise. I feel like all I ever do is leave shores where people are yelling at me, “Don’t give up what you’ve got.” And I’m like, “I gotta go find something.” “Work It” was my guiding light as I was dealing with label and video stuff behind the scenes. I was on a major [Capitol] and I didn’t wanna be on a major. But I thought you could be on a major and still do radical things. I started taking producing seriously after that and exercising it, to mixed results. I was still asking for permission everywhere—like, Could we try this? Missy was not asking.

Klaxons — “It’s Not Over Yet”

At this point, I’m a very exhausted PTA mom. The mommy brigade is just killing me, like my soul is withering. And the Klaxons come bursting through with something I hadn’t heard before. I love when someone cuts new territory; it’s like you don’t even know you’re being squeezed until something comes along and busts open a wall. That’s how I felt when I heard the Klaxons. And just the fact that it goes: “It’s not over, it’s not over yet.”

Have you ever been in one of those periods in life where you’ve already made the decision of what you’re gonna do next? I love that feeling. It’s almost like you’ve got a secret from everyone else because you know you’re gonna go in another direction soon. And that’s what I got with Klaxons. It was the radical joy of a direction and a decision. It absolutely unlocked indie rock for me again. I felt like I had been rejected out of it, but then Klaxons were like, Not so fast.

Lana Del Rey — “This is What Makes Us Girls”

I had never heard of her until she played SNL, but something about her reminded people of me, which I found really surprising. When a reporter asked me to comment on the performance, I was happy to go to bat for her. I completely felt like everyone trashing that performance was sexist. Straight up. Was she inexperienced? Yeah. Did she seem nervous? Yeah. And I’ve seen so many off-key performances on SNL. But because she had that beautiful evening gown on and she was doing this different sort of cabaret, I immediately saw the art in it and thought, She has written a part for herself, because no one else would cast her.

I was in the studio that day, and all these different guys were talking about Lana Del Rey. And I ripped them a new one because I just had it. It was the same nasty attitude that had hurt me, and I wasn’t gonna stand by. That’s why I picked her song “This Is What Makes Us Girls,” ’cause that’s how I was feeling: All we wanted to do was fall in love and have adventures, and we have to go through so much to try to have that. In fact, most of us—myself included—don’t even get it. Men are trying to rule the whole world, and we’re just trying to have love and adventures.

Wolf Alice — “Don’t Delete the Kisses”

In trying to keep up with the guys throughout the years, I had to posture and be more cynical in a way that was actually estranging me from my own femininity. I had this era where I hated everything that the indie radio stations were playing, ’cause it was just a bunch of breathy girlish girls. Then I realized I was mad because I resented that they were allowed to have their femininity.

I heard Wolf Alice’s “Don’t Delete the Kisses” when I was 50. Very hard birthday—the slow downhill roll into your grave begins. But you need that, ’cause it gives you all this wisdom. This is just one of those songs that ricocheted me back onto a different path. At that point there was just this sense that women were holding the center of rock bands with a feminine presence that I deeply longed to have, but had lost touch with somewhere. That feminine intuition—which men can have, they just don’t typically use it. For some reason Wolf Alice reached out a bare hand and were like, Come this way, it’s really easy. At 50, you don’t have to prove anything. Who am I being cool for?

Björk — “Ancesstress”

This is my most recent epiphany. Who would ever think to set a song with this subject matter? Like, you’re not allowed to make a song about matriarchy. It felt heretical to me. She’s a visionary, no question, but this was radical even for Björk. I was looking around and going, Are you guys seeing this? It’s all there in the video, too. This is a matriarchy, and it was completely outside of the patriarchy.

I’ve spent my whole career working against things, and “Ancestress” made me feel like we have traversed a huge distance in that time. With my parents being 90, I’m watching them close up their lives while thinking about where I come from and what my place is on this continuum. And this song is the most important to me right now. I get so excited when someone is doing something that makes me see where we can go from here. Nothing gets me up and out of bed ready to tackle things more. Let’s go back and think about all of women’s lives. Forget the men—they’re there, they’re in our stories.

Featured Image: Onstage in 2016. (Photo: Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images)