The story behind Liz Phair’s infamous early recordings.

For anyone who is more than a casual listener of Liz Phair, then you’re likely aware, and perhaps have even heard, some or all of Phair’s first-ever recordings known as Girly-Sound. These bedroom tapes, recorded on a 4-track in Phair’s parents’ home in the early 90s, were the unexpected catalyst to Phair’s musical career.

Below is a very thorough genesis of

Liz Phair: Chris Brokaw, who’s in the band Come and was in the band Codeine, came out (while) I was living in San Francisco after I got out of school. He came out, and I really loathed to play for people, and as I think I’ve stated, I really hate it, and I really hated it then. I was terrified to play my songs for someone. Chris heard them, he came to visit, and was like “Liz, Liz, you gotta make a tape for me, just make a tape.” He dared me to send him a tape of my stuff. I always take dares — I have that kind of tomboy personality where it’s like, “Oh yeah?” ‘Cause I couldn’t play it for anyone. If I started to, I would stammer, stutter, blush — just complete lockdown. [laughs]

Chris Brokaw: I only knew Liz very peripherally at Oberlin. she was a friend of a friend. My first impressions of Liz were that she was very gracious; generous of spirit; and really smart. An exciting person to talk with.

Liz Phair: Well… I went out there (to SF) to pursue a little romance that didn’t quite pan out at the time. Actually, it was kind of a disaster, and Liz sort of saved my ass by driving me around San Francisco and cheering me up. the scene there was both exhilarating and awful, in a slightly hallucinatory way that seems very San Francisco… it was pretty interesting. They had the biggest dog I’d ever seen in my life, as big as a horse… everyone there was really smart and interesting to talk to, That’s for sure…

“I thought her guitar playing was amazing. She had these strange chords I’d never seen before that sounded completely natural and consonant, but unlike anything I’d really seen.”

– Chris Brokaw on Liz’s unique guitar style.

Chris Brokaw: I was visiting a woman she was rooming with but I ended up mostly sitting around playing guitars with Liz. she wasn’t really reticent; I walked in her bedroom and saw that she had a guitar and I played her some stuff and she played me some stuff. Pretty relaxed. I had been sort of unaware that she played or wrote songs. Then she plays me these amazing tracks. I think one was called ‘Fuck or Die,’ and one was ‘Johnny Sunshine,’ which ended up on Exile in Guyville.”

I thought her guitar playing was amazing. she had these strange chords I’d never seen before that sounded completely natural and consonant but unlike anything I’d really seen. Sophisticated and complex “without sounding that way,” if you get me.

Liz Phair: Then I basically ran out of money and my parents recalled me from San Francisco. I’m suddenly stuck, at the age of 22, back at my parents’ house in the middle of Chicago with no life, no job — nothing — living in my goddamn old room.

I’m living with my parents, and it’s the dead of winter in Chicago, I was hell-bent not to get a job, and I wanted to make my artwork — frankly, because everyone told me I couldn’t do it. I don’t like nine-to-five jobs — I wanted to be paid for my art. I like expressing myself through some form of art. I was a visual artist, doing these big charcoal drawings, dealing with medical textbooks and photographs, where I’d take photocopies and distort the images in some way, to convey a psychological or emotional content beyond just a distorted face. I’ve been doing that and music at the same time, but that was how I lived, selling my art.

From ages 23 to 26, I was a dilettante and refusing to get a real job. I worked out of my apartment in Wicker Park, Chicago. My mom would buy me clothes, and I would mooch food — and mud masks — off friends. I sold about a piece a month, so around $400. I barely made my rent. My mother worked at the Art Institute of Chicago. I made terrible art, cheesy stuff, until I went to college and I was challenged. People wouldn’t let me get away with crap. They forced me to make art that was meaningful. (I had) Freedom. I didn’t have typical job hours, which I liked. I was my own boss, totally. And creative rewards. I felt great about myself when I made a great piece of art. JOB HAZARDS: Abject poverty. And charcoal is hideously dirty — probably a health risk when you inhale it. So I trashed my the room I worked in; I trashed my body, my pores. As much fun as it was making art, I hated all the dirt under my nails. I miss drawing, but I don’t miss the lifestyle.

I worked for him for like three months. Maybe more. I was out of school and I wrote him because he was one of my favorite artists. I’d worked for a couple of other artists in New York and I liked that job, being an assistant to somebody who, you know, you respect their work. It’s not like I was going there for an apprenticeship. I was going there to get in touch with people who I would consider role models for me. . I just knew I wanted to be an artist and I wanted to meet those people that were the people I respected and admired. I figured out how to handle studio visits. I figured out how to host the masses, how to handle a visit to an artist’s studio.

Liz Phair: It nearly killed me. I lived without gas, I ate at friends’ houses, I kept trying to pretend I had money. It was romantic for 25 seconds a day, but that sustained me. I’d been selling my art [mostly charcoal sketches] month by month, never knew when I’d have money, eating beans all the time — it sucked, sucked, sucked.

And I had bought myself a 4 track and I had been playing with it, and I finally thought here I’ve done nothing with my fall after I graduated, and I have this hot shit degree and I’ve done nothing, and I know I’m not going to do anything really with it.

And I made a tape. I was 23. Whenever my parents would go out, I would pour myself a whiskey on ice, have a cigarette and blow it out the window, and sit and record these songs. I sent it to Chris and I sent one tape to Tae Won Yu (of the band Kicking Giant) and (they) just started making copies of it — copies and copies and copies. And that’s all I sent out. I sent out two. And the next time I sent out two. And they just dubbed them, and every other copy you can be sure came from an origin. There’s like an Adam and Eve.

Chris Brokaw: A couple months later she sent me this tape of 14 songs that she had done on a four track, then a month later, she sent me 14 more equally amazing songs. I started telling people, ‘I’ve got this friend named Liz from Chicago, and she’s like the great new American songwriter. Everyone was like ‘Yeah, yeah.’

I thought they were really stunning. i couldn’t believe this trove of great songs. i also loved that she was recording this at her parents’ house, and the tapes sounded like she was singing quietly so that they wouldn’t hear her. i thought they were really exciting, i thought she had instantly hatched as the best new songwriter in America.

Here’s the truth of the matter: I never circulated those tapes at all. i made copies for 3 friends, 2 of whom completely ignored it. (the 3rd was my sister, who made copies for a couple of friends of hers.) Tae, from Kicking Giant, was the one who made hundreds of copies of them and sent them around. At one point I saw a review in some little fanzine and was glad for it. I didn’t know about Liz signing with Matador until I read about it in Tower/Pulse magazine! I’m glad that maybe I encouraged Liz to record her songs, but, the rest was other people’s work.

Laurie Lindeen: My pen pal and former drinking buddy, Chris in Boston, sent me a cassette made by an old college pal, a woman named Liz. He saw Liz in San Francisco while trying to score with her roommate. When the cross-country-trip-for-some-nookie turned unfruitful, Chris ended up hanging out with Liz most of the time. Liz, a painter (like Joni Mitchell), was writing songs and making demo tapes of them on a four-track recorder in her apartment. Chris, a musician, loved them. I was not in a good place to be taking in this demo cassette entitled Girly Sound (or was it Girly Songs? Girly something). At the time I was trying to write a lot of songs and I�m a sponge and a copycat. I was desperately fearful of competition, terrified of being surpassed. My band, Zuzu’s Petals, also had demo tapes and singles, yet I knew Chris wasn’t toting them around, telling people, “Oh, man, dude, you’ve got to hear this!” He did, however, for Liz, and he also gave his record label “an upper-echelon independent label” a copy of her cassette. But my copy of Girly whatever got pitched into a box already overflowing with cassettes (that was later stolen by a sound man), never to be listened to.

The first copies of Girly-Sound began to circulate in the summer of ’91. Both Tae and Chris Brokaw were excellent persons to send tapes to. Kicking Giant was an indie band with roots in New York City and later in the highly influential Olympia, Washington indie scene. Tae lived in New York up until 92 and Liz most likely made her initial contact during the time she spent in New York after leaving San Francisco. Tae distributed the tape to many of his influential underground friends. The tapes made the rounds the rest of 91 and into the first half of 92, and the tapes started to generate a buzz.

Girly Sound is this girl who is a band by herself. The first tape I heard of her was Allison’s made by Tae who knows her. It was just voice and acoustic guitar & Allison said she asked Tae if she (G.S.) was folk and he was like: “Oh no, she would not be into that idea at all.” But then Tae made me a cassette a couple of weeks back & he put 2 G.S. songs on it “Gigalo” and “Flower”; these songs are voice with electric guitar and they became my favorite songs. “Gigalo” goes: “…and it gives me something to laugh about, ‘cuz my real life ain’t fuckin funny. ….OOOOOh lord… why…have…you… forsaken…me?” So awesome and “Flower” my extra special favourite song goes: “every time I see your face I get all wet between my legs. ….I want to fuck you like a dog I’ll take you home and make you like it.” This song sounds like a round with two vocal tracks completely different from each other, and it’s like nothing else I’ve ever heard. Totally inspirational. In fact it inspired me to start my new band Cruella de Ville, which is just me as of yet but I’m open to suggestions. As far as I know, G.S. has only been writing songs since the war, she lives in Chicago now, but will probably be moving somewhere else (Texas?) ‘cuz she is sick of the concrete jungle. If I could remember her name or find her address I would ask her to move to Olympia & be in a band with me. But it’s O.K. cuz I’ll sit in my apartment & write songs & someday maybe we can trade tapes, or send each other songs and record tracks on each other’s tapes & never meet face to face. But still be a band. Is this even feasible? Maybe I should explain that her voice + her words + her melodies & guitar is what makes her songs so great. Tae says: “they are so honest & so true.” And there is no fear in her voice or her words.

Molly Neuman

Girl Germs, Issue 3 (August 1991)

Girly Sound is (so far) Liz Clark Phair. She lives in a suburb of Chicago in her parents’ house. She’s done with college, done with the notion that she may have been the one whose life could have started with a silver step (it didn’t). For now she’s staying home and scrounging for some evidence of her existence. In between her life she’s put out a tape of some of the most moving music made in a bedroom. The tape contains 12 songs with a homemade cover, and is mesmerizing. The arrangement throughout never varies: only her voice (double tracked) and a lone electric guitar playing made up chords, simple elements endlessly repeated until they become a sensual drawl slipping you into her short life. This is her first batch of songs and her self-consciousness shows. Being at her parents’ house she can’t possibly weigh her words with a passion that might complement her music but the result is an unbearable nervous calm that’s unsettling and beautiful. Her singing style is a drawl, as if she’s talking into her own head about every friend, fuck or house she’s known. The evidence comes effortlessly because she’s been walking for miles now. She fills her songs with the mundane details that turn into jewels inside her hesitant mouth, a shy voice singing, “you’ve gotta have FEAR in your heart…” over and over. The mixed up guitar chords are barely enough to catch a thought or a phrase before it’s tossed away. It’s meaningless to offer up Jandek or Daniel Johnston as comparison here despite the obvious qualifications. Girly Sound is My Bloody Valentine, is (My) Sonic Youth, it’s every immensely popular “cool” band we’ve ever spent the night listening to, digging it like a sucker. I know in some ways Liz Phair, like a lot of people would settle for popularity and recognition, a little conversation, no problem. We wouldn’t settle for anything less (meanwhile working at temp jobs, if working at all). We get high and INTO it and RELATE to our “secret personal friendships” with Pussy Galore, Galaxie 500 (i.e. our favorite whoevers), we want to appear in Sassy because we want to swoon and be swooned on. And that is the stupid heart of Girly Sound, staying up all night with a dumb dream of success. The subtle kiss that will emerge once you get past the boo-hoo sentimental meaningfulisms is that this music is really joyful and funny. It’s not a sarcastic in-joke but it’s in the concept, get it? She’s singing with closed eyes, “…you’ve got a lot of nerve coming here after all the times that you tried to pull the wool over my eyes and ears and nose and mouth and don’t be so in love with yourself cause I’m not… and he said you’ve got a lot of nerve painting me like I’m the villain what about all those words like ‘he’s just a friend’ what a load of bullshit…” Out of stagnant fouroclockinthechicagofuckenmornings she’s dashing out the dots of her aimless Liz Phair story, and I am AAAAAAHHH. Send her some cash for a tape, she’ll probably be up to tape #11 by the time you read this. (Liz Phair, [address withheld], Winnetka, IL 60093) – Tae Won Yu.

Tae Won Yu

Chemical Imbalance Magazine (1992)

Liz Phair: This is so bad… People would send me all this money. Like 10 bucks, in a letter, so I’d make them a copy. But I was so poor that I just spent it! [laughs hard] It became my income. It’s horrible. I’m so sorry, but I wasn’t quite as moral as I am now.

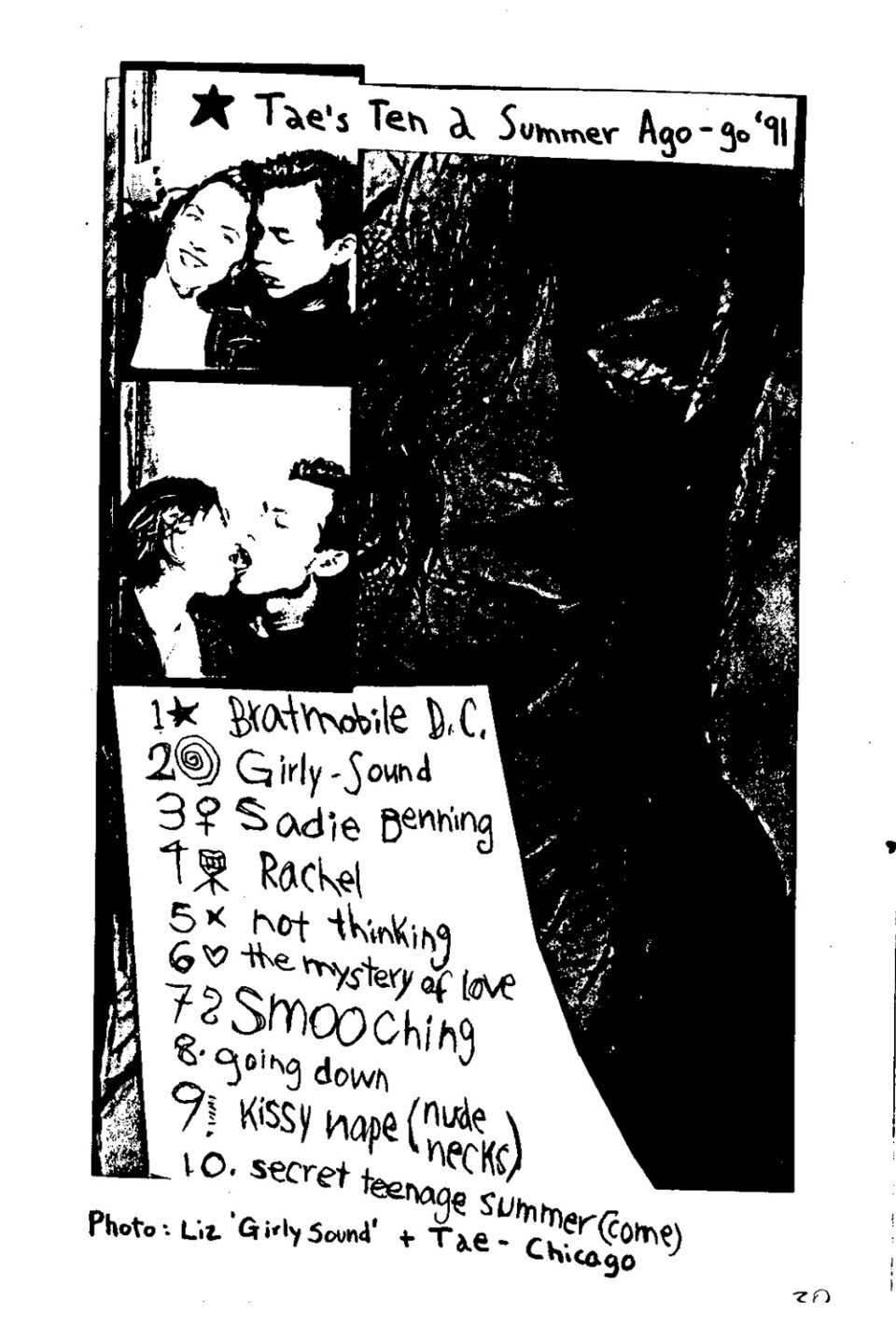

Tae’s Tracklisting

Recorded by Liz Phair, circa 1991

Tape One

1. White Babies 2. Johnny Sunshine 3. Elvis, Be True 4. Fuck Or Die 5. Flower 6. Beg Me 7. Whip-Smart 8. Go, Speed Racer 9. California 10. South Dakota 11. Stratford-On-Guy 12. Shane 13. Six Dick Pimp 14. Divorce Song 15. Go West 16. If I Ever Pay You Back 17. In Love With Yourself

Tape Two

1. Hello, Sailor 2. Wild Thing 3. Fuck And Run 4. Can't Get Out Of What I'm Into 5. Batmobile 6. Sometimes A Dream (Is What Makes You A Slave) 7. Easy 8. Chopsticks 9. Do You Love Me? (It's In My Kiss) 10. Soap Star Joe 11. I Know It's Not Easy 12. Miss Lucy 13. Dead Shark 14. One Less Thing 15. Money

The above constitutes the widely distributed tapes that emanated from Tae. However, this tracklisting was not the same one always sent out by Liz to others. A different collection was sent to Chris Brokaw, as apparent by his description of Girls! Girls! Girls! in its Girly-Sound version. In late 2005, the John Fleming version of the Girly-Sound tapes would surface. Fleming put out a small music fanzine in the late ’80s. Through his fanzine, he met Tae Won Yu. Tae gave him Liz’s address and told him to write her to ask for a tape. Liz then sent him two Girly-Sound cassettes, but included in these tapes were some previously unheard items. There were Girly-Sound versions of such latter songs as “Girls! Girls! Girls!,” “Polyester Bride,” and “Shatter.” Also included were some never-before-heard songs “Valentine,” “Miss Mary Mack,” “Love Song,” “Thrax,” and “Clean.”

Liz Phair: Those tapes were all intentionally about the art form of using a little girlish voice to say really dirty things and play with pedophilia. That’s my way of fisting all the people that I believe exploit a woman’s sexuality. But for the people who initially became aroused, if they listened to what I was actually saying, it was a smack in the face. It would be like Dorothy singing, ‘And I fucked you!’ So at the same time of titillating them, it’s to bring them close enough so I can smack ’em.”

I go in there and rip stuff off — it’s like a library. There’s about 50 songs. A lot of it is juvenile cleverness. There’s verses, there’s choruses, there’s subchoruses. It just goes on and on. There’s a certain naive sound, more breathy. It’s more me.

“Most of the famous women I looked up to were movie stars, not musicians. I wanted to date rock stars; I never, ever wanted to be one.”

Liz on the unexpected reaction to her Girly-Sound songs.

And it (the girlysound tapes) got known around the country, swear to God, through an underground tape network. It was an opportunity and a fluke, and I went with it. The music was the same thing as art, only I got recognition. So I thought, `Cool! I’ll do this for a while.’

Most of the famous women I looked up to were movie stars, not musicians. I wanted to date rock stars; I never, ever wanted to be one. I was working on my art career when my tapes started getting attention, so I wasn’t exactly prepared for a career in music. I had no experience on stage at all.”

John Henderson, owner of the Feel Good All Over record label in Chicago, heard the tapes and was intrigued. Soon Phair moved into his apartment

John Henderson: “Typically, she’d write a song and play it for me and it would be there, entirely. She had such a weird way of playing guitar, because she was trying to incorporate everything that one would hear in a fully produced record. It was percussive and melodic at the same time.”

Henderson would bring in producer Brad Wood to assist in fleshing out the 4-track demos into fully formed ideas. But when Henderson and Phair tried to re-create that feel in the studio with Wood, they floundered. Henderson and Phair soon began quarreling about what direction to take: He wanted a stripped-down but precise sound, possibly with outside musicians; she wanted to rock, on her own idiosyncratic terms. “We both wanted something for me,” Phair says. “He was projecting onto me what he wanted my music to come out like, which was wrong. So I blew him off.”

Henderson was the first member of the music community to find out how tough and stubborn Phair could be. He became so disgusted by what he saw as the musical compromises she was making that he stopped showing up at the studio; Phair moved out of his apartment and began working with Wood exclusively on the music that would become Exile in Guyville.

John Henderson: “I’m reminded of the famous Greil Marcus quote about Rod Stewart, something about how he wanted to be a rock star and all that entailed-sitting by the pool, having sex with groupies and snorting coke-and if he had to write great songs to do it, he was perfectly willing to write them. I think she betrayed her talent in much the same way. The relationship between Liz and me had become so strained that I realized it wouldn’t last long enough for the album to be any good. So I figured why not let somebody else do it.”

Chris Brokaw: Initially I wasn’t really crazy about Guyville. I loved the starkness of the girlysound tapes, and thought that that was the best and strongest vehicle for those songs. I also didn’t have much taste for pop music, at the time, and so the popification of many of those songs left me cold. I also was bummed that several tunes, such as “Girls! Girls! Girls”, had been these long, almost Dylan-esque epics on the girlysound tapes, and then cut down to more sort of bite-sized tunes on Guyville. I really did think that Liz was selling herself short. I understood what she was trying to do, I just didn’t necessarily agree with it. Fortunately for her, everyone else did, so… I listened to Guyville recently and really enjoyed it. It’s an amazingly well-crafted album.

Henderson nonetheless tipped off Brad Wood that Matador was interested in Phair’s music based on the “Girly-Sound” tapes.

Brad Wood was born in Rockford Illinois into a suburban, upper-middle-class family. The Wood family business would be in Funeral Homes, a business passed down from Wood’s great-grandfather to his grandfather to his own father.

Brad Wood: “For a while, it was extremely lucrative. But for most of my adolescence, I’ve seen his money slowly vanish. Demographics control where you’re buried, and Rockford’s shrinking pool of Waspy Presbyterians means a shortage of stiffs.”

Brad Wood founded Idful Music in 1988. Its location on Damen Avenue in Wicker Park played a huge role in that neighborhood’s well-publicized transformation from immigrant launching pad to hipster terrarium. Working a hundred hours most weeks, Wood earned a reputation as a team player, and the fact that he looked just like his Ramen-eating clients helped. His going rate was whatever the band could afford and he learned the art of recording as he went. He mostly recorded the kind of tough-guy, wallet-on-chain, one-word-name bands for which Chicago isn’t famous — Tar, Table, Tool.

Brad Wood: “I own 2/3 of Idful and a partner owns the rest. I bought out a third partner, Brian Deck (drummer for subtly named Chicago grunge band Red Red Meat). We built Idful for less than $60,000 in 1988. Another $10,000 or so invested through 1993, then I plowed another 70 grand into it. We deliberately built Idful to be a facility that worked well for whoever was using it. So the irony’s not lost on Wood that his commercial breakthrough came via a shy, decidedly non-Wicker-Park female singer-songwriter. Wood produced, played drums and bass, wrote and sang most of the harmonies on Liz Phair’s debut album, “Exile in Guyville.”

A lot of the four-track stuff is an extremely frank assessment of men and relationships. I had never heard anybody say those words, let alone sing them. Until I heard her music, I had wondered if there was anyone who really thought that way. I wished I had a girlfriend who was that cool — though that would be kind of scary.”

“John Henderson introduced us. He runs a label in Chicago called Feel Good All Over. Originally her recordings were supposed to come out on that label and he was co-producing it with Liz and me. We started recording, and things didn’t work out so well with John in that capacity, so it fizzled out and we did nothing for while. Later, I called her up and we started recording again, just she and I. We did two or three evenings of recording just for fun where we tried to discover something. We recorded “Fuck and Run,” and that’s when I realized we were on to something. This really spare beat: just guitar, drums and vocals. It had so much exuberance. I love that song. That particular recording is the epitome of what I was trying to capture. That was recorded so simply, just one microphone on the drums.”

It was during this time that Liz ingratiated herself in the vintage Wicker Park scene, becoming friendly with producer Brad Wood, Tortoise drummer John Herndon, comic artist and guitarist Archer Prewitt, Rainbo Club manager Jim Gerbe, Jesus Lizard frontman David Yow, and engineer Casey Rice as well as various members of Urge Overkill and Material Issue. Days were spent in Idful and nights on the town were spent in Wicker Parker staples like The Double Door, The Lounge Ax, and especially the Rainbo Club.

Liz Phair: I was racing around, it was like this point in my life when I was trying my hardest to be like the Shirley MacLaine of the Rat Pack. Y’know what I mean? I was working pretty hard on that. I wanted to know all the coolest people in the neighborhood and I wanted to be someone at the bar that people would want to talk to. My imagination was running overtime at that point so I was really into the whole “scene.”

Then, when I called Matador, they had already heard of it and were like, “Sure, go ahead and record an album for us. Great.”

Gerard Cosloy, co-president of Matador Records: “I think it was sometime late last spring or early last summer (of 92). Liz called on the phone and asked if we’d put out her record. I get a lot of silly, audacious calls. But the day before, I’d read a review of a Girly-Sound cassette in Chemical Imbalance(a punk fanzine). The review was very funny. It was just weird because Liz called that very day and wanted to know if we would put out a single and that was a little presumptuous ’cause we had never even heard anything of hers before.”

Phair sent a six-song tape.

Gerard Cosloy: “The songs were amazing. It was a fairly primitive recording, especially compared to the resulting album. The songs were really smart, really funny, and really harrowing, sometimes all at the same time.

I liked it a lot and played it for everybody else. We usually don’t sign people we haven’t met, or heard other records by, or seen as performers. But I had a hunch, and I called her back and said O.K.”

Cosloy offered a $3,000 advance, and Phair began working on a single, which turned into the 18 songs of Exile in Guyville.

Liz’s coming out party would come at the Lounge Ax in Chicago in January of 1993. this would be the first time many in the press and larger Chicago media and society would hear the name which would become so ubiquitous over the next few years.

Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune describes the night:

She was virtually unknown outside of Wicker Park, her music still a private affair. But when advance tapes of “Exile in Guyville” began snaking down the local rock grapevine, the buzz brought a big crowd to Lounge Ax on Lincoln Avenue one Saturday in January 1993. At the bar next door that night, Phair was sipping tea at a table in back. Stuffed into an oversized coat, a red scarf around her neck, she looked even more waifish than her 5-foot-2-inch frame would suggest. At one point she shivered and leaned forward, gripping her stomach. “It’s nerves,” Phair explained. “I hate going up there.” “Up there” is the modest stage at Lounge Ax. A half-hour later, she was singing and playing guitar before an audience of paying customers for maybe the sixth time in her life, and it would be an ordeal. She refused to make eye contact with anyone or anything except the “exit” sign, and her amplifier kept breaking down in the middle of songs. Then a string snapped, and Phair looked at her damaged guitar the same way a child might size up a three-legged dog. Finally, she glanced pleadingly at the soundboard, and the technician behind it snaked through the crowd to perform equipment surgery. Phair soldiered on, and after 25 minutes, the set-much to everyone’s relief-ended. The songs that night at Lounge Ax were even more riveting as heard on “Exile in Guyville,” released a few months later on the New York-based independent label Matador.