By Yasi Salek

The Ringer, June 27, 2023

Hello and welcome to 24 Question Party People, a new podcast from Bandsplain and the Ringer Podcast Network. Each Tuesday, host Yasi Salek invites a guest from the world of music (and beyond) to answer 24 important questions, like: What’s your sign? What song do you want to hear before you die?

To kick off the show, Yasi spoke with the legendary Liz Phair, whose all-time classic Exile in Guyville turns 30 this year. In the excerpt below, they talk about the album, plus an outtake from the Guyville sessions Liz is releasing.

To hear the full episode, click here. And check back every Tuesday for new episodes.

Well, Liz, this show is called 24 Question Party People, because I like a long and unwieldy name and we go through 24 questions. One is a wild card. We have a little convo within the questions, but before we even get to that, I want to say happy birthday to Exile in Guyville.

Thank you.

An extremely important thing for me personally, and I suppose also for you it was pretty important.

No, not really.

No. Just that’s a—

Just a blip.

Just a blip on the radar. OK. Before we get into the actual 24 questions, is it OK if I ask you a couple of questions about Exile? Because I have this opportunity because you’re right here.

Please.

OK, so you are releasing a song that was recorded for Exile that was from one of the Girly-Sound tapes. The first one, I think. Right? Called “Miss Lucy.”

You ended up not putting that on Exile in favor of the song “Flower,” one of my absolute faves. I mean, are you kidding? “I’ll fuck you like a dog. I’ll take you home and make you like it.” Major for a teen girl like me, I must say. The question, though, is: What made you want to include “Miss Lucy” this go-around on the anniversary?

Well, interestingly enough, though, it is a song that was on the Girly-Sound tapes. This is an outtake from the Guyville sessions.

Right. But you actually recorded it.

So I would have rerecorded it, correct. And I would’ve gone in there with the Girly-Sound cassette, played it for Brad [Wood and] Casey [Rice], and said, “I want to try this one.” And it was just when I was doing Exile in Guyville, I was really trying to play the female part that was implied in the Rolling Stones’ Exile On Main St.

So if Mick was talking about a woman or there was a girl object of his desire in the song, I became that girl. And maybe I answered back, or I said, “Well, that’s interesting how it is for you. This is how that situation is for me.” And so there were two modes. One I answered back, or one I said, “Interesting, but my world’s a little different.”

And so “Lucy,” because it has this sort of intimate, “The girls and the girls they’re fucking, and the boys and the boys they’re fucking.” … And it’s this little ditty that we used to sing as children. I thought that was so subversive and exciting that I thought maybe it could take the place of “Let It Loose,” because “Let It Loose” is about just stuff. And I feel this so often as a woman: We’re trying to do so many things so well. It’s like people, there’s an animal inside all of us, and the “Let It Loose” was. And so I was trying to be like, “Secretly, this is what we’re all doing.” And then I’m like, “No, no, let it loose.” If it’s the Rolling Stones telling you to let it loose, that’s a high bar. So “Flower,” the blow-job queen, was better suited.

You definitely understood the assignment on that one, I must say.

Thank you. Thank you. So this would’ve been the “Flower” position, but it’s an outtake.

Well, I wanted to ask you about the Exile on Main St. of it all. So, famously, you sort of assembled Guyville to be structured as in conversation with Main St., like you said. Was there something interesting and challenging to you as an artist to give yourself limitations in that way?

Yes, that’s very intuitive and very essential to my art. A blank page terrifies me, but a blank page with a box or a triangle and do whatever, that’s freedom. So if I don’t have a structure, I flail. So I need—I’m the kind of person that is really good at taking a structure and walking all over it and being like, “You could look at it this way. You could see it this way. Doesn’t it perform as this?” That’s my skill set for sure.

No, totally. I just really related to it as a podcast artist who did also provide a limitation for myself by having the same 24 questions every time. And I was like, “Wow, I feel seen.” That’s right. I called myself a podcast artist.

Structure. Structure is very important to me. And you wouldn’t think that when you look at or listen to my music. You wouldn’t think that. You would think that I blow apart structure. But it’s that classic thing. You got to know it to blow it.

I’m going to punish you with a quote of yourself. “I remember telling my boyfriend I wanted to write a record, but I didn’t know how. I was a visual arts major, and I concocted the idea that I needed a template—learn from the greats.” So you started asking questions about Exile, and your boyfriend was like, “Yeah, it was a huge record for them, but it’s a double record, Liz.” You said: “I can remember him sort of joking, ‘You should totally do that,’ but being sarcastic as if I couldn’t possibly, and I remember in that moment being like, ‘Really?’” In addition to limitations, do you perhaps thrive on people telling you no?

I certainly meet the moment when people tell me no. I wouldn’t say I thrive, because I would prefer a green light and a clear lane, but I absolutely do meet the moment.

Like, “Oh, really? Really, bitch? Watch this. Hold my beer.”

I don’t wait awhile. You know what I mean? I tackle it right away.

You started the album Guyville with John Henderson, and speaking of “no,” he had a very different idea of how he wanted it to sound as opposed to how you wanted it to sound. And you were basically like, “That’s cool. Bye. That’s nice. Bye.” And he said—this sent me to the moon—“I’m reminded of the famous Greil Marcus quote about Rod Stewart, something about how he wanted to be a rock star and all that entailed: sitting by the pool, having sex with groupies, and snorting coke, and if he had to write great songs to do it, he was perfectly willing to write them. I think she betrayed her talent in much the same way.” Now, the feminism left my body a long time ago. However, I cannot help but notice that some men get really mad when you don’t agree with them.

I don’t think that’s John’s problem. John’s problem was a sense that those who can’t do, teach. He was an expert at great music. He knew great music, and he introduced me to a lot of interesting New Zealand bands. I definitely soaked up a lot of indie from him. But I mean, I soaked up a lot of music from my parents. I soaked up a lot of music from college. I soaked up a lot of music from going to shows in high school. The idea that these indie rock men who bought records or, in John’s case, put them out would have a better knowledge of music than I do. Even taking piano lessons, guitar lessons being introduced with my parents too, like classical, symphonic—everything traveled around the world.

That he would know what was good and what was bad was what I was fighting against entirely. That quote is perfectly encapsulating of the attitude that I was met with many, many steps of the way, and it’s just his taste is different than mine. I have a different idea of what I like, and he has a different idea of what he likes. I didn’t betray my talent. I’ve been growing and flourishing my talent the entire time, trying out new things, giving myself new challenges. I could not perform live. I had never been on a stage. How could I betray my talent when I hadn’t even begun?

This transcript has been edited and condensed. To hear the full episode, click here. Check back every Tuesday for new episodes, and to subscribe to the feed or check out the Bandsplain archives, click here.

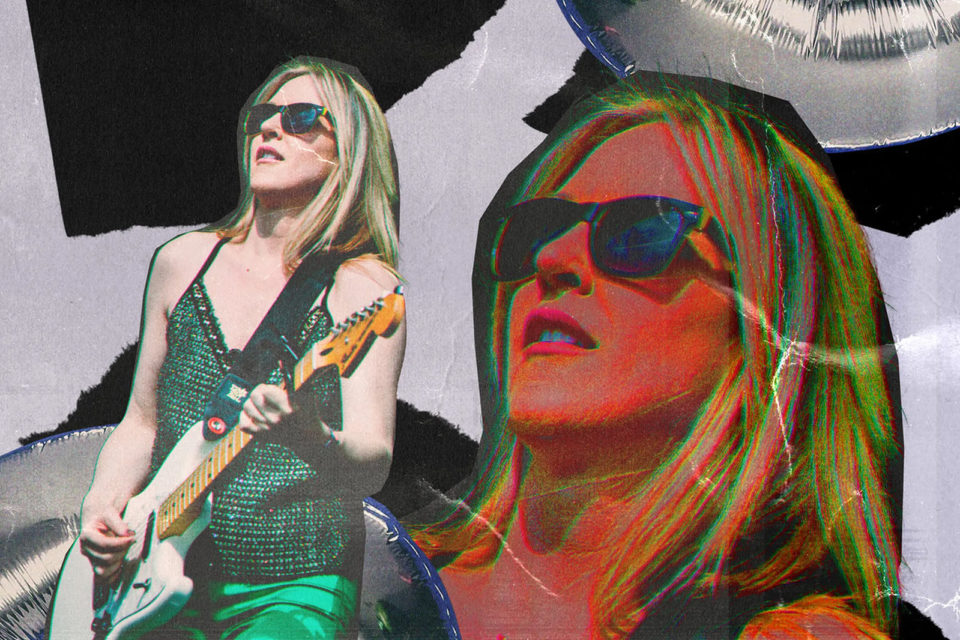

Featured Image: Liz Phair (Photo: Getty Images / Ringer Illustration)