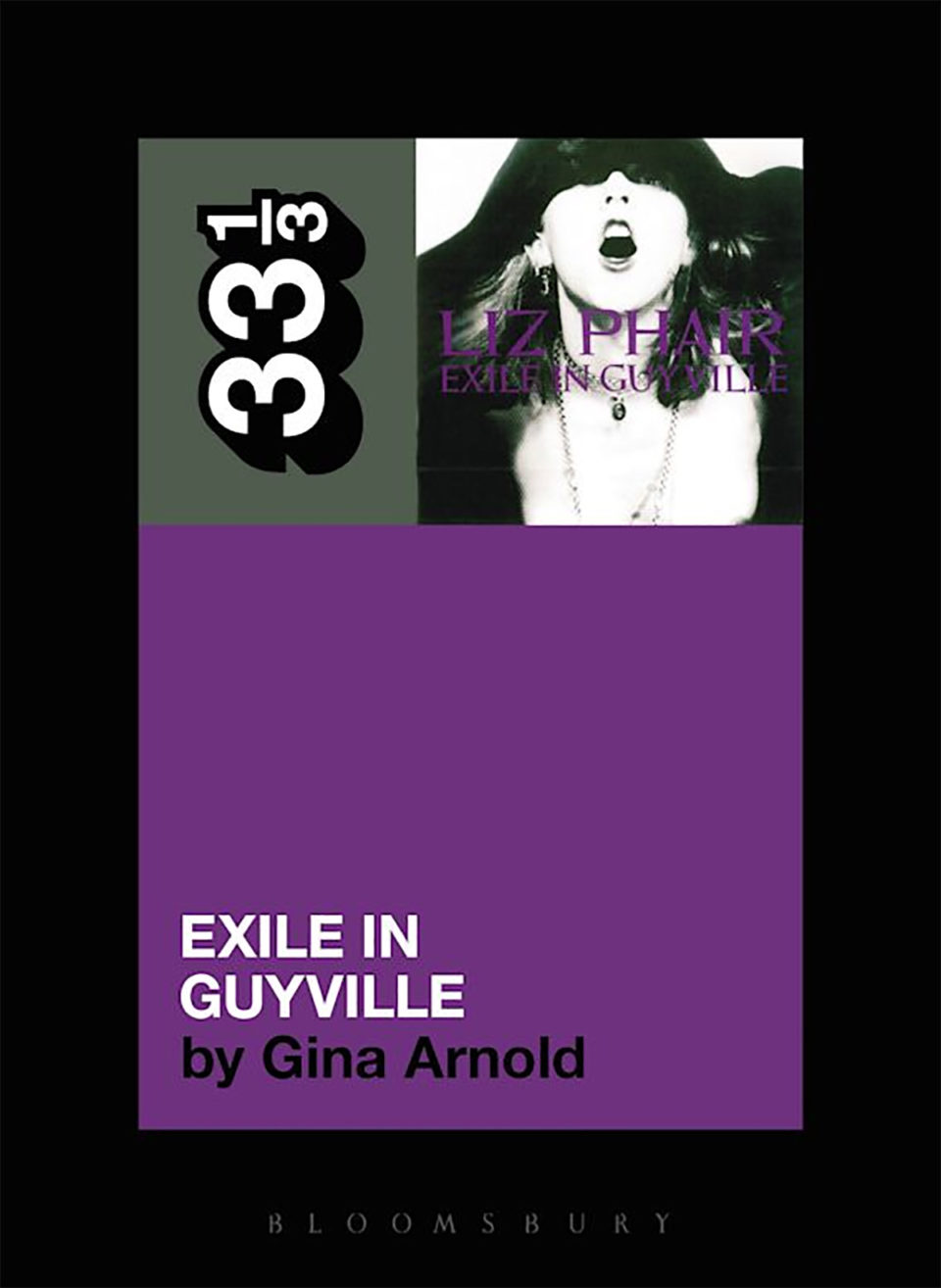

How a suburban Chicago songwriter wandered out of a John Hughes script and recorded one of the decade’s masterpieces

In 1993, no rock record was as divisive as Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville. With her 18-song double-LP debut, Phair pried the lid off her life and sang away secrets. Even though it landed right at the apex of the cultural moment for “Women in Rock” and riot grrrl, Phair was something else. Her feminism was not wrapped up in dogmatic choruses, her rage was articulated in quiet disses tangled up in sublime indie-pop. Guyville was all guile and jangle. Phair dispensed with the innuendo and explained exactly, and explicitly, what she was game for. “Flower” includes these lines: “I want to fuck you like a dog / Take you home and make you like it.”

Even more novel and exciting was the fact that Guyville was, in both form and concept, a rookie’s rogue retort to classic rock: Phair conceived it as a track-by-track response to one of the pinnacles of swaggering musical masculinity, the Rolling Stones’ Exile On Main St. Combined with its literate pop craft, untethered libido, and utter confidence, Guyville was about the most glorious, girly Fuck You ever.

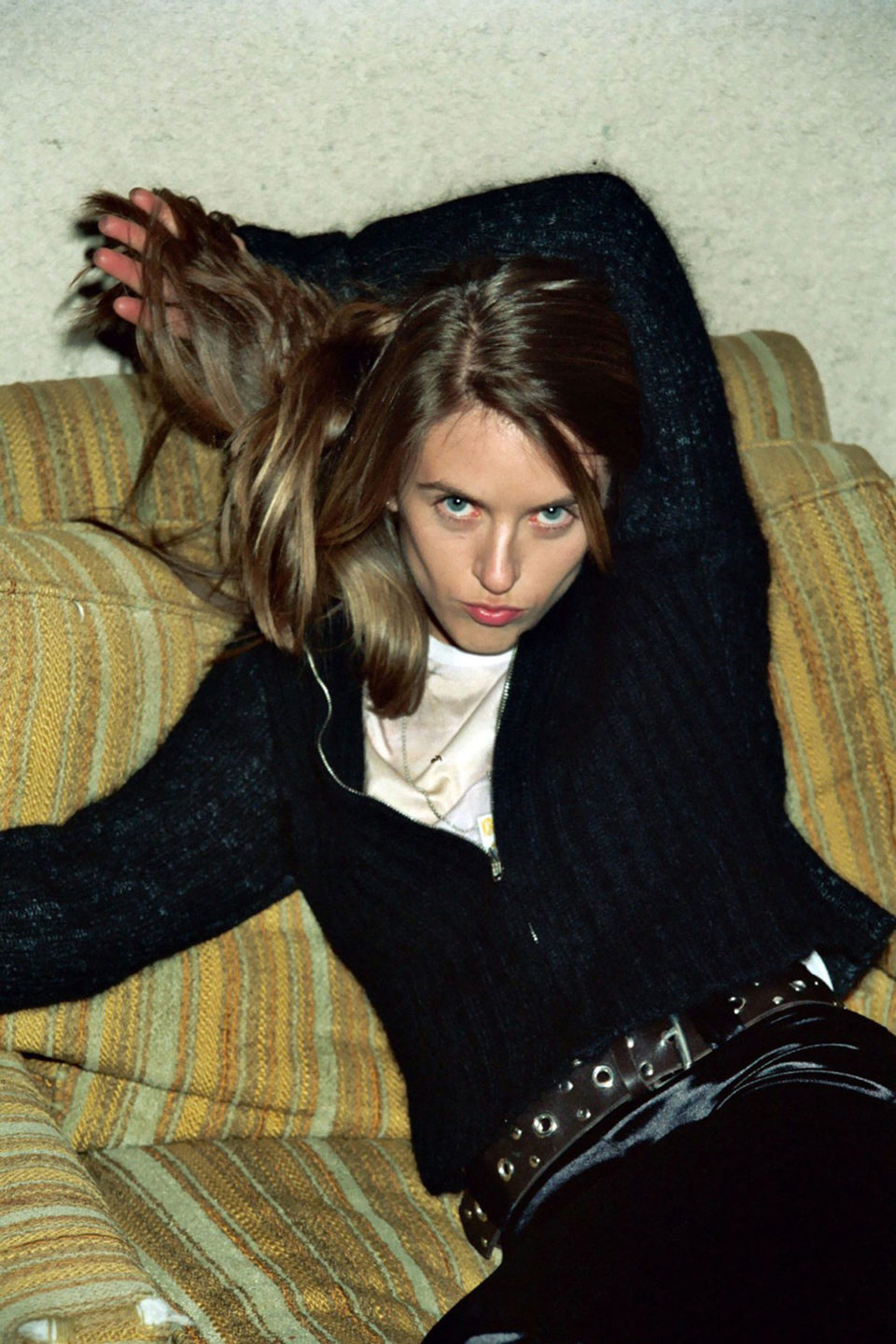

It exploded, fully formed, from Chicago’s indie-rock scene centered out of the Rainbo, a bar central to a then un-gentrified Wicker Park, where Phair, an unemployed artist, was embedded. It was remarkable as a pop album, but also as an unrepentantly feminine shot fired by a newcomer to a scene known for its terse, aggressive, virtuosic albums by bands like Jesus Lizard and Shellac, dudes who had been around since indie-rock’s inception and had helped foster its unwritten rules. Phair, a privileged, well-educated woman from the suburbs who barely thought of herself as a musician yet had grand ambitions, didn’t play by those rules — soon, however, she would be the scene’s most visible emissary.

Inside of a year, Guyville racked up 200,000 in sales when selling a tenth of that was considered “indie rock gold.” She topped SPIN’s 20 Best Albums of the Year for 1993 (“In a year when men preened like objects and women claimed the authority to make their experiences rock’s main subject, Phair was unrivaled,” wrote Eric Weisbard) and reached No. 1 on the Village Voice Pazz and Jop Critics Poll. Soon, she got a Rolling Stone cover, a Good Morning America appearance, a major-label deal, and a side hustle as a TV composer (she won an ASCAP award for her work on the CW version of 90210) — but it was Guyville that made her a star and an icon.

Liz Phair, vocals/guitar/piano: I had written all these songs and recorded them on my own — the Girly-Sound tapes. I had just moved back [to suburban Illinois] from San Francisco and was living with my parents. John Henderson, who had a little label called Feels Good All Over, had contacted me. I was hanging out at Northwestern with frat guys, I just wanted to get out… John’s apartment became one of my destinations. He introduced me to bands and spent a lot of time to teach me about good songwriting — which I definitely learned, but I was only half paying attention and not taking it super seriously. He had a room and said, “Just move in here, it’s super cheap.” And we started working on the record.

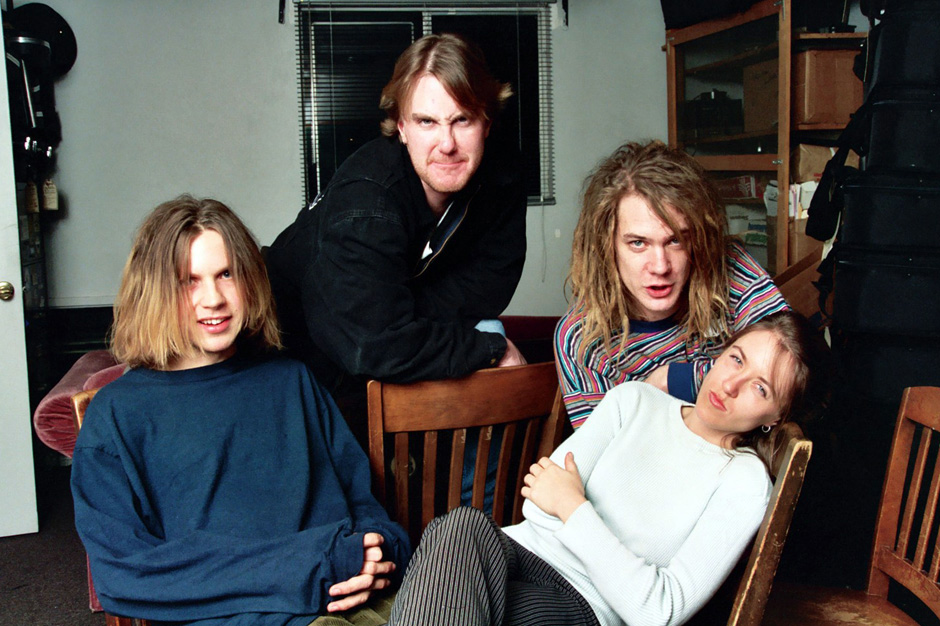

Brad Wood, producer/drums/bass/guitar/keyboards: In the fall of 1991, John Henderson told me about this amazing songwriter named Liz that he was working with. He thought my recording studio might be the place to make her record. John invited me to his apartment to listen to the Girly-Sound cassette. Liz was there, but asleep in the other bedroom. My first impression was, “Holy shit, I’ve got to find a way to record this music.” I just remember the long walk home from John’s apartment, feeling kinda drunk with the possibilities. I also remember worrying that I couldn’t afford to screw this up.

Mark Greenberg, multi-instrumentalist, Coctails: Brad had his recording studio, Idful, right smack dab in the center of Wicker Park, so it was a natural place where a lot of local bands recorded.

Phair: I was living this completely post-college, flat-broke, only-cared-about-going-out-at-night existence, shirking my adult responsibilities. In the studio, when we had gone in to record with John, he and I just didn’t see eye to eye about how we wanted to record or how it would sound. I thought, “Why are you telling me it should be this way?” He really felt strongly that he knew more about tasteful music than I did.

Greenberg: I remember talking with Brad once after a show somewhere after a couple of beers. I had mentioned the Coctails were trying to record with Brian Paulson, who had recorded Slint’s Spiderland, which we were all in love with. Brad was sort of deflated at hearing that, saying all he needed was his Spiderland to really kick off his career and make the jump to “the big-time.”

Phair: I had a falling out with John and I threw off what I felt was the yoke of John. I don’t remember how it all went down, but I thought, “Who is this guy and why is he in charge of me?”

Wood: Things came to a stop by December of 1991. After Liz moved back to her parents’ place in Evanston, I figured that was the end, but the potential of those songs kept nagging at me and I called Liz in January 1992. I drove up to Evanston, drove her back to Wicker Park, and she and I recorded “Fuck and Run” that night. It was a big success and we even had time for a drink before I drove her back home. Hours of driving. Things progressed at that snail’s pace: me driving 45 minutes to her parents’, she and I driving back to the studio for 45 minutes, record for a few hours, maybe watch some PBS, drive back to Evanston to drop Liz off, then finally drive back home to Wicker Park. I saw a lot of Lake Shore Drive in 1992.

Phair: Brad came to [the suburbs] to visit me a couple times. I remember serving him bisque at my parents’ house in Winnetka.

Wood: When we tracked “Fuck and Run” in one night and I saw Liz dancing over and over again to the playback, I knew we had hit the right formula.

Casey Rice, engineer/guitar/vocals: When Brian Deck left Idful [which he’d co-founded], Brad asked me to work there as an engineer. I knew Liz from the neighborhood. I think she and I had hung out a bit and talked about art and music. Liz was scheming about putting together a band and I fit the bill being a kind of meat-and-potatoes guitar player. And the fact that I worked at the studio made it easier. I also think Liz’s mandate about the Rolling Stones idea made me more attractive as a guitar player. I was in a band that was very “rock.”

David Roth, Rice’s roommate: Casey had been working as a faux finish painter, and working with his band, Dog, which was kind of falling apart at that time. We spent a lot of time hanging out smoking dope and listening to Stooges records. Then he started working at Idful. He was really a workhorse, you could tell that he was doing something that he felt a lot of passion for.

Phair: I was dating this guy and I was living in this apartment where I was writing the songs for Guyville. It belonged to some friends who had vacated and they’d left behind these cassette tapes, and one was Exile On Main St. I was listening to it and thinking about how to make a record, and I was fighting with [this guy], and he said, “Well, why don’t you do that one? That’s a double record” — but he was kind of sarcastic about it and so I was like, “Okay! I will!” I listened to it over and over again and it became like my source of strength — my involvement with Exilewas like an imaginary friend; whatever Mick was saying, it was a conversation with him, or I was arguing with him and it was kind of an amalgam of the men in my life. That was why I called it “Guyville” — friends, romantic interests, these teacher types — telling me what I needed to know, what was cool or what wasn’t cool. I developed a very private relationship with this record, listening to it again and again and again.

Roth: I spent some time hanging out with Liz, she’d come by the apartment, and we’d talk at the Rainbo; she was pretty charismatic, and had a pretty sharp intelligence. We’d talk about music, I would play her Cows, and she was really impressed with Shannon Selberg’s lyrics. She had kind of an arrogance that a friend of mine attributed to her going to Oberlin, but she was a pretty good drinking buddy, and offset any snottiness with a funny ability to talk shit, and exuded excitement about creativity.

Rice: She struck me as a smart and interesting woman who came from a privileged background who had aspirations that probably didn’t fit mom and dad’s expectations of her. Much like many of my other friends.

John Herndon, drummer, Tortoise: I was hanging out a lot with Urge Overkill, who lived across the street from the Rainbo. [Liz and I] were always hanging out there with them, mostly just getting wasted together, listening to Funkadelic. That happened a lot, actually.

Chris Lombardi, Matador Records: It was a pretty heavy dude scene in Chicago at that time. A lot of pretty aggressively male bands congregated there: the Albini/Urge Overkill/Jesus Lizard scene.

Phair: I made these crazy notes and charts. I took all of [Exile on Main St.‘s] songs and studied the arrangements, and I had these symbols, rudimentary symbols, like a swirly line or a wave would represent what I now understand as reverb or a chorus pedal. I would use them to map out my songs with symbols that represented the same thing — like this is a perfect response, or from a similar point of view. Like you are talking about tripping home from being at someone’s house sleeping with them and you run into your other girlfriend while you’re doing your walk of shame — which is what I thought about “Rocks Off.” So I wrote a song like I was the girl he ran into, which was “6’1″.” It sounds totally crazy, but that’s how deep in it I was. I went to a wedding with my family that summer, that August, and I had my stacks of paper and my Walkman where I was listening to Exile in my headphones.

Lombardi: She was really into the Stones.

Phair: We were at Brad’s loft, and we were talking because I was pissed-off and I wanted to keep making this record, and he says, “You need a label.” And I asked what’s the best label. He says, “Matador Records.” I called up Gerard [Cosloy], got him on the phone. He had just read an over-the top review of my Girly-Sound cassettes in a fanzine and I called up like an hour later.

Gerard Cosloy. Matador Records: My only prior knowledge of Liz was a review that Tae Won Yu of Kicking Giant wrote of the Girly-Sound cassette in Chemical Imbalance. I’d known Tae for awhile and his review was pretty compelling, and I sort of made a mental note to try and check it out — not so much from the label scouting side of things, but just to hear it.

Lombardi: I had read reviews of Girly-Action [sic] — that was about all.