Wood: A few days after they’d heard a FedEx’d cassette of our recordings, they faxed me a two-page contract for a single album. Liz signed it and we faxed it back to Matador. Liz then decided that the record needed to be a double album to match the Stones’ Exile on Main St.. She asked me, “Do you think Matador will give twice as much money?” They did. It was five thousand bucks.

Phair: Matador gave me a tiny amount of money — ten, five grand? — but enough that Brad was willing to work with me, and we would record in and around his scheduled sessions. He would have these money gigs and then whatever night or afternoon was free, he would call me to come record. I was doing nothing, I had no job, I was practically squatting in Wicker Park, just into going out on the town at night and being a fun girl. So, I would come in whenever he was free.

Greenberg: Being signed to Matador made sense, but at the time, it didn’t mean she was going to be huge. [Matador had acts like] Railroad Jerk, Mecca Normal, HP Zinker — all good bands, but not exactly household names, you know? So for me, hearing she’d been signed to Matador was, like, “Oh nice, more people will know about her.”

Rice: There was a lot of grumbling about how someone who was relatively unknown and certainly not established as a performer should be offered such an opportunity. I remember people citing Barbara Manning as someone more deserving of a record deal than Liz. I agreed in some respects — that it seemed “unfair” in that regard — [but] when was the music business about being fair and in the business of promoting interesting women artists?

Cosloy: [I was] pretty stunned. Between “Fuck and Run” and “Divorce Song,” I absolutely thought, “This should be a record right now.”

Wood: There was a lot of talk about how to record a song before we actually got started. Liz usually got her guitar part down quickly and then we moved on. Feeling was more important than perfection. She didn’t take any shit and that was cool. As a musician, she initially was pretty apologetic about her guitar playing. I love her playing and was happy to record her goofy, fluid style. Lyrically, no one could touch her.

Phair: Casey brought the snarling, sexy rock part of it. He is that dude. He had kind of a savvy rock thing and Brad was more jazz-rock — he had gone to music school and had that wealth of knowledge and love for the past. I don’t know if Casey did this — I doubt he actually did — but I imagine him doing the cigarette-in-the-headstock-while-he-was-performing thing. Everyone brought something totally different and there weren’t a lot of arguments — until it got big and then it was harder.

Wood: Almost every song on Guyville started with Liz playing her guitar to a click track or drum machine or looped hand percussion. Drums were often added last, which is the opposite to how a lot of rock music is recorded. Ass-backwards.

Phair: The worst part would be when Brad would talk for a really long time about an amplifier and how it grew out of this and that and I would just be like, “Ugggggh. God. [Sighs].” I brought in my own cheap little Peavey amp and I had my own way of setting it. I wouldn’t be changed from it and he had to work around it — it was like a sonic challenge. It was like the kind of amp you would buy for a child who you didn’t think was going to be good at music and so you didn’t want to invest in it. Like the worst possible amp. It was my security blanket. I would not be taken off this amp, with my settings and my guitar.

Dan Koretzky, Drag City: As far as professionalism goes, they were extremely competent. Brad seemed to be making records with bands that might otherwise be running from Steve Albini’s studio in tears. Casey tried to put some hair on the alopecia-like sounds Brad was known for. Which in hindsight was fairly prescient.

Wood: There are a lot of really cool vocal asides on Exile on Main St. — “Woo!” “Yeah!” “Alright!” — and I deliberately put some of that into Guyville. On “6’1″,” you can hear me say, “Yeah!” as I sit at the drum kit ready to play. On “Never Said,” I open the song yelling, “Yeah!” and I shout as each chorus approaches on that song. I tend to sing and make stupid sounds as I drum anyway, so hollering while recording these songs was really natural. Adding harmonica, lots of maracas and shakers, Casey’s guitar solos and the tone of his guitars — especially on “Mesmerizing” — the looseness of the grooves: it was all a part of the appeal of [Exile on Main St.].

Phair: I was up at my parents one night — I remember it was time to decide whether I was going to put “Flower” on or not. I woke up in a cold sweat, a panic, knowing that if I did that it was going to be a big deal. I really felt like I had to do it. I knew what portrait I was painting — I thought it was part of a well-rounded portrait, fulfilling all of what a woman is.

Wood: “Explain It to Me” was fun to record — there are cardboard boxes and pillows being played through all kinds of effects. The other is “Shatter” — a song whose lyrics still amaze me — and is maybe my favorite Liz song ever. I played “percussion” on that song and it’s me hitting the kitchen countertop with two mallets. Casey devised a great way to set up two guitar amps facing each other — with me in the middle with a Telecaster — turned way up, and depending on which way I leaned, would generate a different pitch. He was great at setting up controlled feedback situations.

Phair: I hadn’t even wanted to be a recording artist; it was completely a side thing for me. I was concentrating on being a fine artist and working on my drawing. [People] weren’t wrong to judge me [as a novice] because I often present myself more plain that I really am — you could put that on my epitaph.

Herndon: I don’t remember her ever talking about her music, or Guyville. I remember talking to her about art.

Koretzky: I do recall having one very long conversation about music with her, where she passionately argued to me that there were a lot of teenage girls out there who were waiting for music they could relate to, and she was making her music specifically for them.

Janet Beveridge Bean, singer-songwriter, Freakwater/Eleventh Dream Day: It seemed like she came out of nowhere. It was super punk-rock in this way. I didn’t think of her as a musician, and I liked that sort of disregard for convention. She came from the suburbs, and then all the sudden everyone was really hyped on this album she was making.

Phair: I remember some guy had come back to my apartment after the bars closed, and we were going to get high or something, and this happened a lot, and I took great pleasure in this. They’d be like, “Blah blah my music, I’m going to do this, blah blah.” And then I would be like, “Oh, I’m recording a record too,” and they’d be like, “Really?” I’d put it on and they’d be, like, “Oh my god, you really are recording a record.” And that was always a proud moment, because I could blow them away because it was a totally good record.

Lombardi: When we got the album, Gerard and I flew to Chicago to see her pretty much immediately. The record struck us as something important and special right off the bat — it got our attention. We know it was something we couldn’t fuck up.

Rice: I’m sure that the confounding aspect that a blonde, petite, cute, suburban young woman could write stuff like this appealed to them, too.

Phair: First time they came to Chicago, I remember [Chris Lombardi and Gerard Cosloy] hanging out with Urge — they wanted to party. [Laughs hysterically.]

Cosloy: It’s also funny because this was all happening right around the time we were doing our joint-venture agreement with Atlantic, and Liz never came up. We played a few songs for the guy we did the deal with, but there was zero interest on his part in making Guyville one of the Matador/Atlantic joint releases.

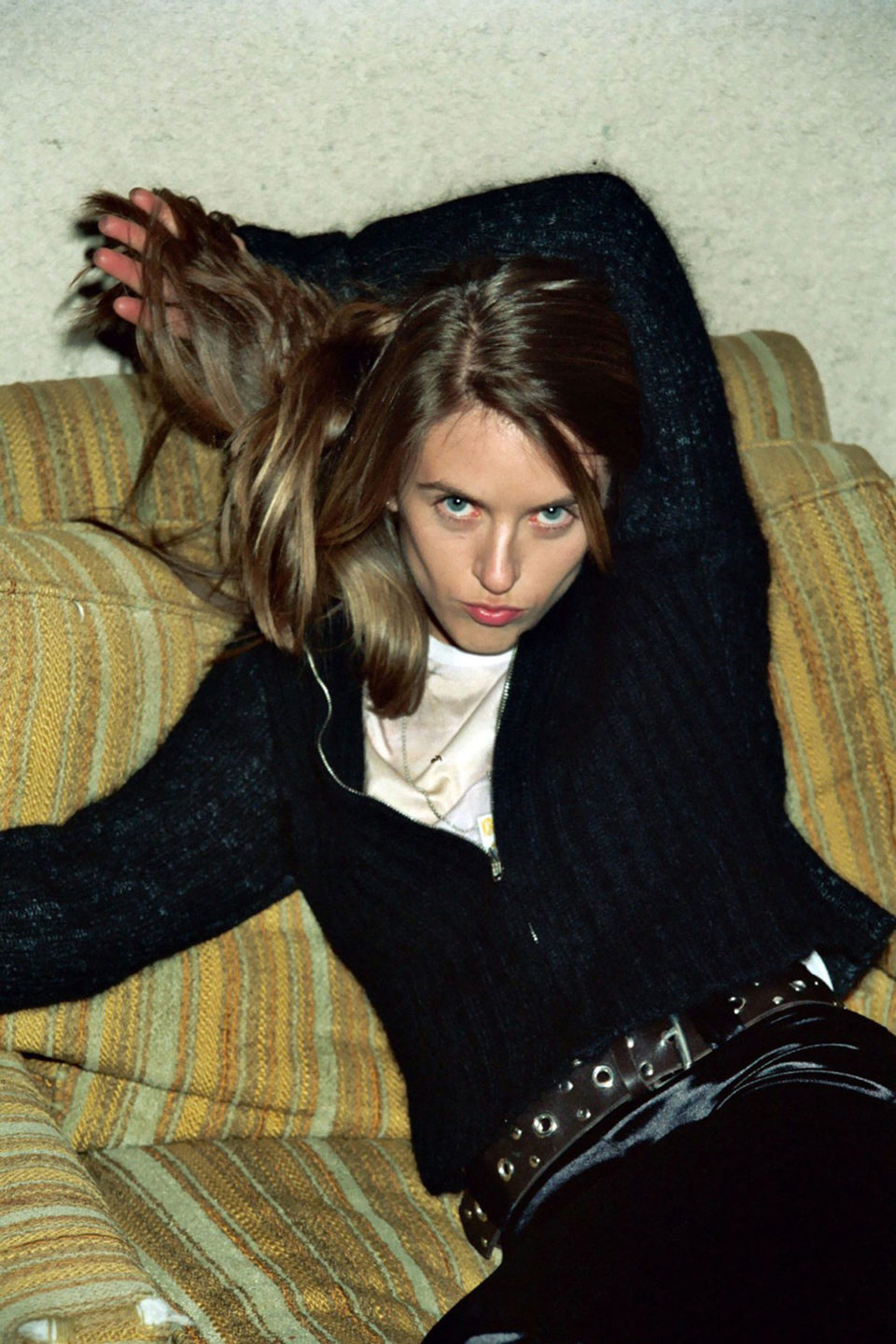

Greenberg: We asked Liz to open for our record-release show for our third LP, Long Sound in ’93, before Exile came out. It was a well-attended show and maybe it was one of the bigger crowds she had played in front of to that point. I do remember her killing it one moment, then losing it at another, like a magician who fumbles a trick only to end up nailing a bigger and better one. She was charming, very attractive, and a bit badass.

Phair: I can remember listening to [Guyville] in my apartment and thinking it sounded amazing. I was so proud and felt a rush of power because I had done something I knew was good. Listening back at my parents’ house, privately, feeling terrified that my two worlds would collide and it was not going to be pretty. I had kept them separate. It would blow my cover.

Wood: The day we finished, Liz, Casey, and I had sequenced the album and were then playing it off onto quarter-inch analog tape to be sent to mastering. We sat in the control room listening one last time to all 18 songs in order before the rest of the world heard it. I cried a few times.

Rice: I don’t remember Brad crying. I think he likes to embellish the Liz Phair myth.

Koretzky: Brad and Casey were brimming with extremely false modesty about how amazing the record was. Before it was even mixed, they were opining about how legendary it was going to be.

Wood: I was certain that Liz had just done something incredible and that lots of people were going to take notice. I was so proud of her and what she had done on her own and with us at Idful. We made predictions on what the sales might be. Liz said 3,000. Casey said 30,000.

Phair: Guyville is wrapped up in how the songs were written and in the way it was created and came about: It’s that girl, that girl having people say you can’t do this, you aren’t good enough to do this, you don’t know what you are doing — and me getting enough rage in me to say, “I have as much of a voice as anyone and I have as much of an education as anyone and even if I didn’t have the education or the musical knowledge — it didn’t stop me.”

By Jessica Hopper

Spin, June 24, 1993

View article ›