By Devin Friedman

GQ, July 2003

Liz Phair asks to be picked up at her gym, a depressing brick hangar pasted into the concrete flatlands beneath the 405 in Manhattan Beach, California. She can’t drive, because her license has been revoked for what she claims are unfair reasons (her argument is, as far as I can tell: I was speeding, but so was everyone else!), and she needs a ride to Capitol Records. Liz Phair, her fourth album, will be released this month, almost exactly ten years after Exile in Guyville came out and a generation of self-conscious men who grew up in the suburbs, went to liberal-arts colleges and moved to hip urban areas fell in love with her. (I count myself among them.)

At the time, Liz Phair was 26, wickedly smart, mortally ironic and performatively sexual. She was like our girlfriends, or the girlfriends we would have invented if we had the technology. We had a special affinity for her because she was authentic. And if there was one thing we prided ourselves on, it was that we were people who knew from authentic. And because her songs were so intimate, and her record was on an independent label (requisite, we were certain, for authenticity), we were convinced that Liz Phair actually belonged to us. While everyone else was rubbing one out of the image of Madonna in a conical bra, we had Liz Phair, and only we really understood her.

In the next ten years, Liz Phair relased two more records (1996’s Whip-Smart and 1998’s whitechocolatespaceegg) and moved from Chicago to L.A. She was single, got married, became a mother, got divorced and is now single again and living in a slender town house two blocks off the water in Manhattan Beach. She has a son, Nick, blond, asthmatic and addicted to a video game called Impossible Creatures. She says being a mother is like living with a troll but in a good way. She shares custody with her ex-husband, who lives five minutes away.

I wait for Liz, watching the housewives of Manhattan Beach fleeing the gym in their sweat-ringed stretch pants. I am prepared to overanalyze any aspect of her appearance so I may generate some theory about who she has become. This turns out to be unnecessary; her appearance is not nuanced. Liz emerges from the gym in a tiny camouflage miniskirt and a tiny and very pink halter top that just hides her nipples. She is flawless — her skin, her makeup, her blond-highlighted stick-straight hair. She looks as if she has been put through a refinery. There are no traces of the prematurely jaded indie rock girl, no sign of the reflexive fear of beauty everyone who wants cred seems to have. She looks like Madonna or J.Lo. Liz Phair once cancelled a tour because she couldn’t bear the force of the collective attention trained on her; but this is a Liz Phair who wants people to look at her.

We drive to Hugo’s, a health food restaurant in Hollywood. Liz is on a raw-food diet, which she says is making her feel a million times better.

Capitol is spending more on this record than was spent on any of your previous releases. Are you going after a wider audience?

Yeah. This is my hope for the record: that people who like good music but who wouldn’t necessarily seek out Liz Phair will like it. My new record is really about the Cincinnati me that wants to drive through the countryside really fast in the summer, blasting music.

Who is the Cincinnati you?

The me who relates to rubes.

Is this like when an actor does a blockbuster to pay for his indie project?

I don’t think that way. I wanted to make — and I think I did make — a great record that’s popular. It doesn’t have to be everybody’s cup of tea. I just felt like rocking. Is that so much of a crime? I felt the need to rock my ass off, to feel like a chick again.

There is, is there not, a song called “Hot White Cum”?

It’s called, officially, “HWC”. But yeah.

So what exactly is the song about?

It’s about what it feels like when you’re really in love and having great hot monkey sex. For so long, men ejaculating has been such a touchy issue for feminism, because of AIDS, because people are wary of sharing bodily fluids. But when you’re really in love and having great sex, that’s part of what you want. My parents haven’t heard it yet.

Have you been dating?

Yeah. I’ve got this Kate & Leopold thing now where I don’t want to date anyone who isn’t calling me up properly. But I made out with a marine in a bar recently. Now see, if I’d stayed married, I never would have experienced that. I would have thought of marines as a totally different kind of thing.

It was a bar pickup?

Yes. We got kicked out of the bar for obscene whatever. I was on his lap. It was beyond groping. We were fully… whatever. He was unbelievable. I was so close to walking out there with him. I never do that. I’ve got a tawdry reputation, but I make a much better girlfriend than a one-night stand. I’m not into commingling with strangers, but my God. Oh, my God.

Liz Phair has always been frank about sex. She sang in a matter-of-fact way about having boyfriends who like to watch TV while they have sex, for example, and about being able to come only when on top. This in no small way contributed to the sense that we somehow knew her, that we had a special relationship with her, and it attracted the kind of creepy fans of which she’ll speak below. But this unglossed sexuality is part of Liz Phair’s greater skill, singing intelligently about intimate things. Through the course of her records, we watched her fall in love, get married and have a baby. And now we have to watch her make out with a marine, which, to all the English majors who felt cool for listening to her in 1994, feels like a betrayal.

To hear that what women really want is a marine — that’s my worst nightmare.

Every woman does want a marine. You know why? Because they’re noble, they put themselves in harm’s way for their country, and they can protect you. That’s an alpha male, baby.

I’m just a little defensive.

I think you should be. How do you think it feels to be a woman? We live with that, buster. Every day. Every channel change. Wait till I’m in power; it’ll be a whole new world of insecurity for you guys.

Why do you think you got divorced?

I know why I got divorced. I got divorced because I shouldn’t have gotten married. I got divorced because the person I was with is kind of emotionally closed off and I am a person that needs to connect. And whe we had problems — I have a lot of bad qualities that make me difficult — he’d pull back. The dynamic that needed to be there to get us over the hard bumps wasn’t there.

Did he want to get divorced?

I think because he’d been married before, he didn’t want to get divorced again. But believe me, he worked late, if you know what I mean.

So for the past five years you’ve been working on the new record?

I’ve been recording the whole time, doing different sessions with different producers. And I’ve been writing. Poetry and short stories.

And acting too, right?

I have an acting manager now. I just shot a film where I played a yoga instructor. I’ve been offered a role in a movie with Noah Wylie and Ileana Douglas. I don’t know what it’s called, but I heard those two people and I’m like, I’m in. And I think I even have more than three lines.

How did you get an acting manager?

It’s easy to get a manager when you are, like… a songwriter.

You mean “when you’re kind of famous”?

That’s what I’m trying to say.

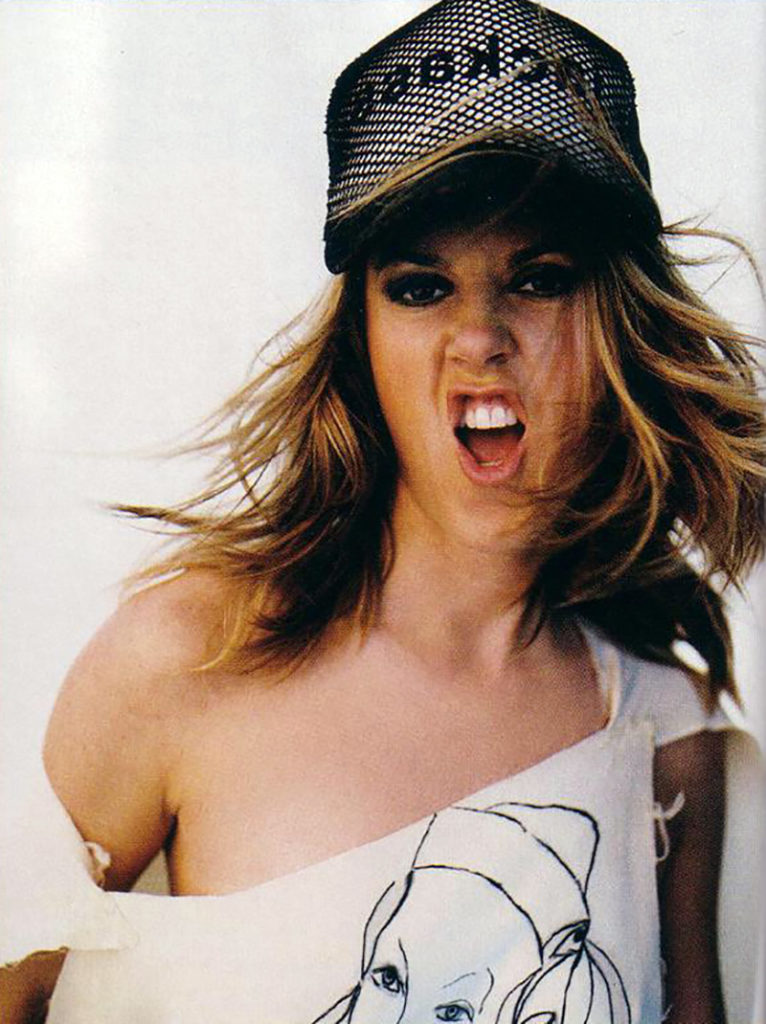

We spend an hour in the office of Andy Slater, president of Capitol Records. His windows give out onto Hollywood Boulevard, burning under the midday sun in high contrast, the trees green against bleached concrete and stucco. Andy says, “Okay, Liz, go change for a second,” and Liz disappears into the conference room to put on the outfit she’ll wear three days hence, when she shoots the video for “Why Can’t I?”, which she and Andy and all of Capitol hope will be her hit single. Slater has about him an air of preoccupation, impatience; he paces the office talking into a tiny headset plugged into a cell phone stuffed somewhere on his person. It’s hard to talk to him without feeling as if you are wasting his time. He is dressed up like a Laid-Back Rock Guy: His hair is stylishly cut to appear scraggly, and he’s in jeans and high-top sneakers that look cheap but are actually made by some obscure designer in Japan.

On the way to the Capitol building, I asked Liz why she was going to try on clothes for the president of her record label. She said, “He tends to micromanage the details. Which unfortunately he has the right to do because he made Fiona Apple and Macy Gray big. It can be an unpleasant feeling. But he’s very good with creating an image for an artist.”

In a few minutes, Liz enters in a flowered miniskirt and an army green CBGB T-shirt over a long-sleeve thermal undershirt, trying to fasten an army-paratrooper’s belt and suspenders. She looks like a GI Olsen twin. It’s become clear that Liz Phair is being packaged to appeal to teenagers. The single “Why Can’t I?” is on the soundtrack for How to Deal, a movie starring Mandy Moore and aimed at people who have never heard of Liz Phair. She tugs at the miniskirt and asks Andy if the outfit seems too “little kid-ish”. “Just reassure me,” she says. “All I want from this little meeting is to feel reassured that I’m not going to look like the cute Liz, I’m going to look like the cool Liz.”

“To me,” Andy says, “that looks cool.”

Then Andy tells a story about hanging out with Shelby Lynne, whome he describes as “just mind-blowingly amazing.” Another Capitol executive jokes that Liz is getting jealous, to which Liz says, “I’m not jealous of Shelby Lynne. If you were bringing in some teen… I don’t know. But Shelby Lynne just isn’t–“

“An edgy outsider like you,” says Andy.

Andy wants Liz to feel that she is still an “edgy outsider”. This is the purpose of the big black boots and the CBGB T-shirt (which translates, more accurately, as “I was an edgry outsider”). Of course, it’s kind of difficult to be an authentic “edgy outsider” if the president of Capitol Records is picking out your clothes. But Liz is actually being marketed like Tampax or Maybelline: a product for teenagers. She is abandoning the overeducated thirtysomething demographic (among them, rock critics) for the portion of the population whose ennui centers on the PSAT. To those of us who believed she belonged to us, it’s disappointing. But we’re not really relevant anymore, anyway.

We finish our conversations over plates of crappy chicken fritters and expensive berries at the Mondrian Hotel.

Your new record was produced by the Matrix, the team that made Avril Lavigne’s record, right?

Not all of it. Four songs. But because the Matrix set a production bar that I had to kind of match, the songs I picked that other people produced were the bigger, poppier ones.

This is by far the most polished, heavily produced Liz Phair record to date. It sounds as if it cost a lot of money and involved state-of-the-art technology. Overall, the album is catchy, and on certain songs, like the ballad “Good Love Never Dies”, the high production value feels right. But there are generic rock-guitar riffs sutured onto songs, like rock-guitar riffs are sutured onto the opening music on Monday Night Football. In the song “Why Can’t I?”, there’s this part where she sings the line I hardly know you, and then there’s this little computerized Liz voice that chimes in, …hardly know you… hardly know you. It sounds like something you’d hear on Nickelodeon. The lyrics lack the honesty and the sting we expect from Liz Phair. Which may be because she didn’t write all of them; she cowrote “Why Can’t I?”, with the Matrix. “The lyrics I wrote,” she admits, “are more sophisticated.” It makes me think Liz should have left her Cincinnati self in Cincinnati.

This is your first record since 1998. It’s been a while between paychecks.

If I make money again, when I make it again, I’m saving it.

How much money do you make if you’re Liz Phair?

Liz Phair doesn’t answer this question, exactly. I don’t blame her. She does, below, answer the tacit question (Are you worried about money?) I was posing. In case you’re wondering, though, Liz Phair has released three major records over the past ten years.

Exile in Guyville sold 397,000 copies; Whip-Smart, 392,000; and whitechocolatespaceegg, 267,000. These are all respectable numbers. But selling a million records over ten years does not make you filthy, stinking rich.

It’s hard to make money if you’re Liz Phair. Because you take seven years betwen records! [Laughs.] It’s not a very good business plan. I’ve done, like, okay. I’m definitely down to the wire now. It’s, like, time to get out there.

Have you met a lot of people who felt really attached to Exile in Guyville?

There’s a difference between the people who were drawn to my first record in general and the people who took it upon themselves to approach me about it. And in the beginning, the people who approached me were kind of freaky. They were emotionally needy, that kind of grabby person. Broken is the word that comes to mind — and I kind of fled from that audience.

Did you have a hard time dealing with being an instant icon after Exile?

I really wasn’t prepared for a lot of stuff that happened after Exile. But I didn’t think about all the performing stuff that I was so bad at, and all the photographs and having a symbolic meaning in pop culture. I didn’t bargain for that, and at the time it really overwhelmed me.

The whole fame thing. It squashed me. I didn’t want to do it anymore. Some people hated my first record, they thought it was shit, and they were vocal about it. Especially in Chicago, they thought I was hyped beyond what I deserved. And I just felt really threatened anywhere I went. I couldn’t function in that kind of scrutiny.

Putting out this record has to be scarier in some way, because it’s geared to be popular.

I’ve got to be completely honest with you: I’m not in that paradigm. That sounds like the way I used to think. Like “Will people like me?” “Will I be accepted or rejected?” I’m much more invested in “What did I do today and how well did I do it?”

What if you weren’t special anymore? Do you think you could just be normal?

No. Because I never wanted to be normal. I always wanted to be exceptional. Here’s what you don’t know about me: Before I was anything, I was special. Because I was talented. I was kind of quiet, I was nice, but I was special.

We love Liz Phair because…

1) During lulls in this interview, she sang “Good Vibrations” in a charming, absent way, and her voice was surprisingly beautiful.

2) She looked pretty hot on her first Rolling Stone cover, in 1994.

3) It was one of the worst-selling Rolling Stone covers of the ’90s.

4) She wrote a song called “Fuck and Run”.

5) When she found out a photograph of Paris Hilton’s nether parts was circulating on the Internet, she said, “If I had Paris Hilton’s pussy on my computer, that’s all I’d look at.”

6) whitechocolatespaceegg (Capitol, 1998)

7) She made twice the number of albums as her supposed foulmouthed rock-girl counterpart Courtney Love — with half the hype.

8) She spoke frankly about her personal life instead of insisting that all people should care about is her art.

9) She writes lyrics that are more like sad, sexy stories than pop music.

10) She’s an expert dream interpreter. — D.F.

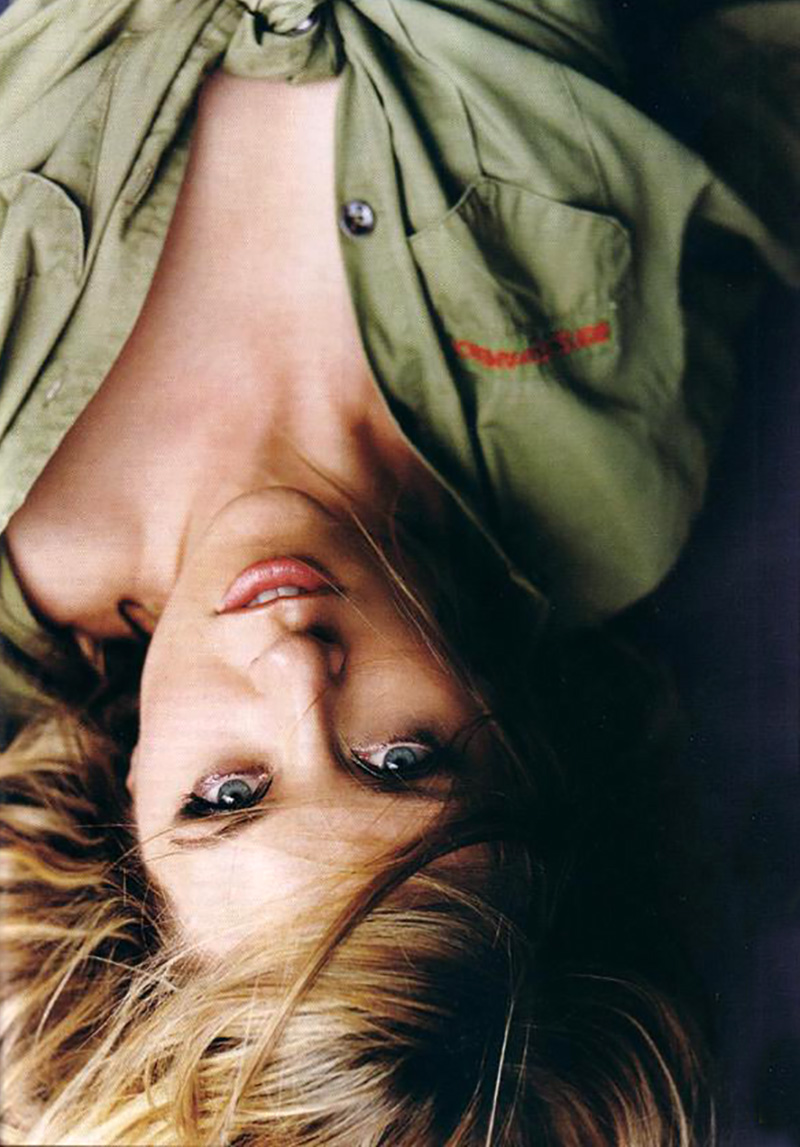

Featured Image: Liz Phair (Photo: Peggy Sirota)