(Not necessarily in that order)

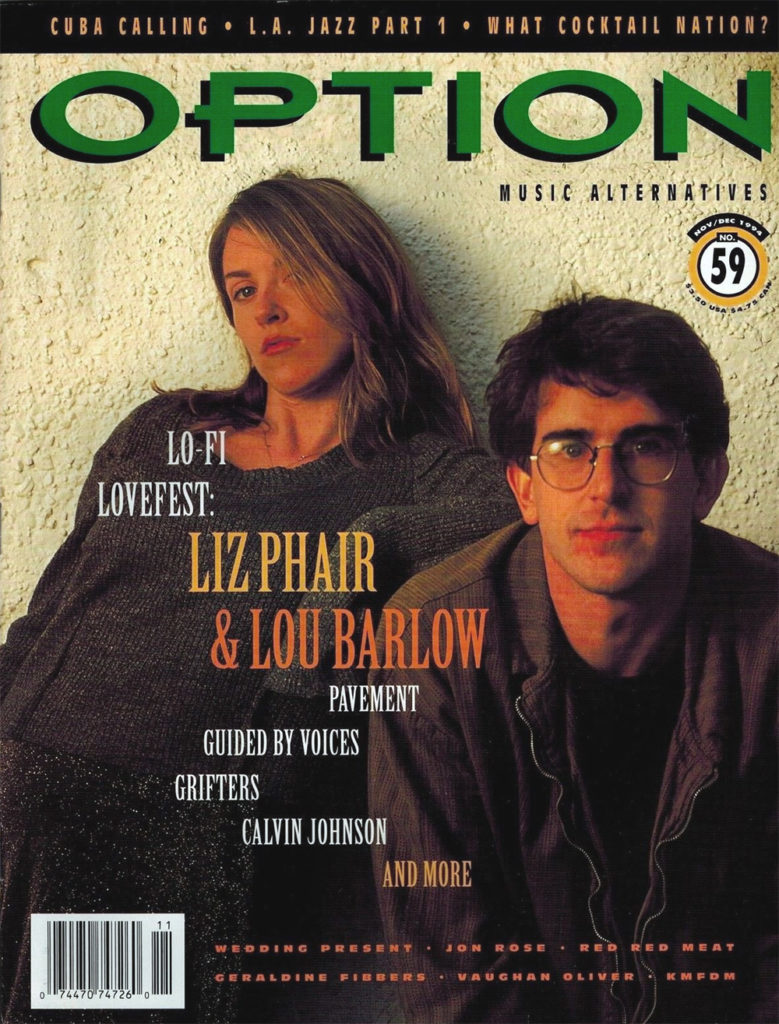

Grinning widely, Lou Barlow opens the door to a room on the eighth floor of Chicago’s swanky Meridian Hotel, and the sweet smell of hash incense wafts into the hallway. Inside, a slightly dazed Liz Phair bobs up and down on the queen-sized bed, where she’ll remain for much of the afternoon.

Barlow, 28, is a soft-spoken latchkey kid from the Boston ‘burbs. Growing up with parents who were unusually supportive of his musical endeavors, he opted to postpone college and live at home until he was 21. After leaving Dinosaur Jr. early in the band’s career, he has recorded under a variety of monikers, including Sebadoh, Sentridoh, Lou B., and the Folk Implosion. A confessional lyricist, he pours his soul into aching songs about lost love, found love, uncertain love. Though much of his music is recorded at home on a four-track, Sebadoh’s latest album, Bakesale, is the band’s most accessible yet.

Phair, 27, is the daughter of a Northwestern University research physician and an instructor at the Art Institute of Chicago. A product of the Chicago ‘burbs, she is self-possessed and conversationally savvy. Her songs — obsessive, compulsive, neurotic, flip and always sexually charged — also focus on love, though with a knowing wink. On the cusp of superstardom with her much-anticipated album, Whip-Smart, Phair is living up to her startling 1993 breakthrough, Exile In Guyville, and her earlier, self-released, lo-fi Girly Sound cassettes.

Throughout their conversation, MTV flickers in the background as Phair easily coaxes Barlow out of his self-imposed shell, freely responding to him with her own flamboyant, THC-fueled metaphors. She even offers Lou advice on how to propose to his girlfriend: “Don’t be a fucking dork — walk out and get a ring! With a decent-sized diamond in it!”

Pigeonholed

LIZ: No one ever asks me about my guitar playing. No one’s ever fuckin’ asked me about how I write songs. I have all these things to say about that, but no one cares, ’cause it really doesn’t matter what I play on guitar. Even if I play really interesting guitar songs, the only thing they care about is what it’s like to be an upper-middle-class cute girl with smart parents singing dirty words. You know? No one wants to talk to my band. I know why they like me. I know what they want. And that’s depressing, ’cause then it’s a job. IT’s not a quest for change. But the music is what got us into this room today. It’s what we’re here for.

LOU: I’m just getting to the point where I’m trying to ignore what the printed things say. It’s like, OK, they’ve pigeonholed you, but there’s nothing you can do about it, so ignore it. I mean, it doesn’t matter how much you do right, ’cause in the end the people decide.

LIZ: It’s like a political campaign.

LOU: Yeah, I was thinking about that today. I’m some kind of fucking weird politician and I can’t believe that. Through default I found myself in this position of being a strange politician and spending most of my time talking about something that I don’t have time to do anymore. It just totally sucks.

LIZ: This is what happens. This is the truth of the game. I had a fucking breakdown about two weeks ago and I figured it all out. It hit me like a big old ugly hammer. I was exhausted from something that most people would consider a really cushy job, and I just couldn’t figure out what was wrong, and then I got it. I got everything that I do and why I was asked to be here. It’s just so surreal. In entertainment they don’t tell you the job until you’re there.

LOU: I don’t know, ’cause I’m not in your position at all.

LIZ: Yeah you are. You’re in exactly the position I’m in. You’re saying the exact same thing that I’m saying.

LOU: Yeah, but the pressure on me is less than it is on you. I guess I still don’t feel claustrophobic, ’cause I still feel that there’s not very many people listening.

LIZ: It really changes your life to feel claustrophobic. It means you have to take active measures. It’s a matter of deflecting. Earlier we were talking about being the center of attention. Really, the change in my life has been being paid so much attention. The money thing — I lived better as a child. Well, not really. I don’t know. But it’s like deflection. I don’t have a good pro-active measure to protect myself from being the center of attention. I have good passive-aggressive measures. I don’t look at who’s in the room anymore. I don’t even try. I used to be a person who would make eye contact with people. Now I can very easily slip in and out of places without ever knowing who else is in the room.

LOU: See, I just spent my whole growing up looking at the ground. I’m serious. I would look down all the time, and it’s taken me up until the last couple of years to even be able to look at people.

Sex In Cyberspace

LIZ: It’s a computer world. My boyfriend is totally Internet. Well, we don’t have Internet yet, but we want to get all that stuff. We’ve got America Online.

LOU: It’s kind of exciting. It’s like, I don’t believe anything’s sacred, you know? I don’t think anything should be any particular way just because it always has been. You know, there’s Internet sex, and it’s all just sex. It doesn’t matter.

LIZ: But there’ll never be a substitute for personal interaction, I don’t think. Phone sex? I don’t even relate. I don’t even know anyone who has phone sex. Do you have phone sex?

LOU: No, I never have.

LIZ: Have you seen this software — it’s the weirdest thing — where you can couple this woman with lots of different little things, like bondage partners. On a computer nobody can interfere with your enjoyment. Anyway, one of the things she has is this little 8-ball lover — which is so sick. To this day I ask people what it means. It’s a guy with the head of an 8-ball, like a pool ball, and he’s about up to her knees, and he comes running up between her legs and just start fucking her. I’ve got a great imagination, but I have no I idea what that means.

There are some things that are sacred — like real sex. I guess there’s the danger of feelings. If you’re more into using a computer than getting down, then don’t have kids — and that’s just as well. As I see it, we can stand to strain our gene pool. Fuck it. Those people — we don’t want their genes. Don’t propagate!

LOU: That I understand. I like that.

Socializing

LIZ: I wasn’t extremely social when I was in high school.

LOU: But you said you made eye contact with people when you met them.

LIZ: Well, yeah, all right, so I was extremely social. But I knew people who were more social than I was.

LOU: It’s not a bad thing to be social. I think it’s kind of good.

LIZ: My mother’s extremely social. But I was much of a closet academic geek as anybody.

LOU: You’d have to be. I mean, your music indicates that you’d have to have spent some time, like, thinking about shit.

LIZ: Sure, yeah. But it pays for me to be one thing and not the other. There’s more pressure for me to be gregarious, social, cute and fun than for me to be a great musician. I think that’s sexism.

LOU: That’s the classic… It annoys me so much whenever I read anything about your records — the way people are actually surprised your’re singing the things that you’re singing. They think you’re somehow stepping outstide of your role as a woman. I’m like, “What fucking role?!” When I got your record I reacted pretty strongly to it, like, “This is a rare kind of thing.” And then when I started to read what people thought, it annoyed me so much.

LIZ: I brought so few values to it — and they brough me so much.

LOU: Exactly. And for people to think that the sensitivity in my songs is somehow a gender role reversal is just ridiculous. That’s just my upbringing.

LIZ: But maybe the kind of man you are hasn’t been seen in a public sense for a while. You know how centuries have their trends as to who’s the voice that’s listened to? Who do we want to look throught the eyes of now? I mean, I think there are gender roles. I did it all over my own album — “Look at this, I fuckin’ gender flipped!” — without knowing it. I’m about as girlie as they get on some levels. I think of myself in a multi-ethnic, multi-economic category, but I’m perceived as a very specific item.

LOU: And I’ve sung certain songs from a feminine perspective — just trying to understand power. Power between men and women — that has a lot to do with a lot of the songs I’ve written. I’ve had to actively think: what would it be like to be in that position? I’ve tried to really get into the situation and understand it.

LIZ: That’s what my whole first album was, for me. That’s the whole Exile thing: to appropriate “What the fuck is wrong with you?”

Sex In the Real World

LIZ: My dad’s chief of infectious disease at Northwestern, and what he does is work with AIDS has been around probably about five to ten years longer than you think, and I think to a large extent the fear of it is just the swings of paranoia in our culture. As far as I can see, it’s like people dying from any disease. It’s pretty much like any pathology of disease.

I don’t buy that whole idea that there was this change in sexual politics because of AIDS. It could have been anything, and I think whatever it was would have affected our sexuality too. I think anything could have been inserted in the place of AIDS. And it pisses me off. [laughing] I don’t know. It’s my issue. I just think it made everybody scared in this really evil way. It didn’t make people scared in a constructive way. I think it was just a catalyst for the paranoia of our time.

LOU: It didn’t make people scared enough to actually stop…

LIZ: To stop doing it. It just made people like, “I’m looking out for myself and you are a threat to me in a gross way — in a way that I can look down upon.” Like a status thing. I thought people who wouldn’t really get the disease spent a lot of time thinking about it. People who are still becoming really infected and developing symptoms and living with it — they’re kind of passé now and we’re just mulling over how we feel about them. I think the fear of AIDS is a scapegoat. I think we were born aimlessly neurotic; too many choices and not enough direction.

The Lo-Fi Theory, Take 1

LIZ: I like that four-track sound, man. I’m going back, I’m fucking going back!

LOU: I write songs using a four-track.

LIZ: Yeah, exactly. It’s a sketch pad.

LOU: Yeah, totally. The thing with my four-track stuff is, I’ll just sketch it out so hard and in so much detail that I don’t want to take it to a studio, ’cause it’ll ruin all the tracings and all of the layerings and the texture of the sound. But then, I record in the studio all the time with Sebadoh. If you have a band — guitar, bass and drums — I think it’s best to at least try to experiment with the studio, ’cause there’s got to be a good way to get a good studio sound. As long as you can hear the voice, and the voice has some texture to it. Liz, the way you sing has that total four-track feel. It really registers with me.

LIZ: That’s the thing about live stuff. With that kind of volume and wattage attached, you can’t have that kind of intimacy you want. On a four-track you can pound the drums, throw it all on a track, do anything you want at the intensity you want, and be like Chet Baker, you know?

LOU: And it’ll have so much of a presence over the top of everything else.

LIZ: Just floating like a little Cheshire cat.

LOU: That’s exactly it. It gives it personality. I found that I had to learn how to sing my songs in a stronger voice.

LIZ: That’s really what it is. It’s learning how to sing. I was going to take singing lessions. You’ve gotta become a performer. It’s not even related to the studio situation. Like, Brandford Marsalis loathes my music because of the lack of musicianship, but at the same time I’ve been in loads of music classes, so there’s a certain amount of conceptual musicianship. So what’s the difference? It’s the lo-fi thing: indie rock humbled us.

The idea that there are God-given musicians, and it flows freely from their souls — that’s not what we are. We’re privileged, trained, white kids, so we just get down on our knees and we’re like, “I will not pretend to perform. I will just do my best to be the same way, like a soul, straight.” Lo-fi feels like it’s giving a clean offering. Do you know what I mean?

LOU: I think so.

LIZ: ‘Cause we’d think someone was bogus who had a lot of glitz to them; like it was so clearly contrived. But we’re probably very contrived on some level too. We know what we’re doing, but we respect more than anything our ability to just freely come up with something. So we go lo-fi to be humbled before the gods or something.

LOU: I go lo-fi because that’s all I have.

LIZ: Really?

Television

LIZ: I watch HBO a lot. I watch a lot of movies. Some TV — Beavis, Married With Children…

LOU: I just watch comedy. Comedy and nature documentaries.

LIZ: Oh, the stoner channel — absolutely a must. Nature and God in the living room!

LOU: It’s between that and comedy. And then CNN, you know, occasionally.

LIZ: CNN? I don’t trust them anymore. It’s like the New York Times.

LOU: I have this belief people who work real jobs, like out in the actual working world — for them, TV somehow serves this real function, like this meditative function. It’s really strange. It’s like they need to watch TV. My father’s like that. He works eight hours, dressed for the job, and he comes home and just turns on the television and just fucking channel surfs the entire time. It seems to me like a lot of people do that.

LIZ: I think you’re exactly right. I know exactly what you’re talking about. I’m sitting here trying to fathom why that is.

LOU: Just the monotony of having a nine-to-five job. I’m really happy that I escaped from that. There’s something really debilitating about working a real job. I always thought that watching TV was pretty similar to sitting out in nature and just listening to the breeze bow. I never believed that one was better than the other.

Nostalgia

LIZ: How old are you?

LOU: 28.

LIZ: I’m 27. So we’re roughly the same generation. Your babysitters would be my babysitters, right? So ’70s rock. It’s like you’re stuck. I think there’s something that happens to people as they reach adulthood. They spend a lot of time trying to figure out what first hit them about rock’n’roll. It’s like the first time you took a drug. You want that first time back. You want that first deviance from the world as you know it.

LOU: Right.

LIZ: And so you’re pretty much destined to rehash that over and over again. It’s scary.

LOU: And that’s Urge Overkill!

Lo-Fi, Take 2

LOU: I’m super defensive about this, ’cause I just spent the last three weeks in Europe and every fuckin’ day it was like, “Why are you lo-fi and why do you think you’re a loser?” It’s exactly like you were saying — you’re just this middle-class kid, you know, whatever. I just don’t understand that lo-fi…

LIZ: OK, Veruca Salt goes into the studio and do their vocal take billions and billions of times until it is perfect and it’s not patched together. It’s that professionalism.

LOU: So, it’s lo-fi not to do that stuff?

LIZ: Yeah, it’s not lo-fi not to do that stuff.

LOU: Well I do all that stuff all the time.

LIZ: But not the way everyone else does. You do it in your own flaky, retarded way.

LOU: Yeah.

LIZ: I think I sound more mainstream working retarded than I do when I’m being professional. And that’s the disparity, because you think you’re selling out completely with these lo-fi productions, you’re using all the cheeseball moves, and then radio won’t play it because the sonic quality is not that of a tapestry that can meld into the secretarial pool.

LOU: Yeah, but I do all of the recording techniques to totally emphasize the voice and the lyrics and the emotional impact of the song, which to me is being as commercial as I could possibly be. I feel like I have always been completely commercial, but I can never tell anyone that at all.

Pop In a Box

LIZ: Idiosyncrasies are what keep you unsold. Like Cindy Crawford has one little mole, but the rest is great. But she has one defect. You have to hone it down till you just have a few acceptable defects. I think that’s commoditization. You get to pick your three worst flaws and you can exploit them, but everything else has got to be goddamn perfect. And then you win the lottery. Wouldn’t you like to win the lottery? The music lottery?

LOU: Just become a huge, huge star?

LIZ: Really quickly, under a different name. And then go up to Canada. I’ve always said I wouldn’t mind being off on my own.

LOU: Being off on your own? What do you mean?

LIZ: The freedom you have once you become a commodity in the extreme.

LOU: So when are you not a product? And who is not a product? There’s no way I could properly answer those questions. Either way, people’d grumble. So what am I going to say? — “There’s nothing wrong with being a product.” Or, “OK, there is something wrong with being a product.”

LIZ: The thing about being a product is that, partially, it gives you power to be who you want to be. But obstructively, you forget why you wanted to be powerful in the first place. You have a big, booming voice, but you have less to say, ’cause you’re spending all of your time worrying about your bigger, booming voice. At some level, that’s why you played your songs for a friend to begin with. You were hoping that somebody would see the true you, and that this would mean something. That the true you was not just your mother’s illusion. There was something you could offer that was your own creation. You could offer something that was poetic. Commodization blurs that line really fast, because the world of business and the world of vision are too much alike.

LOU: It took a really long time before I was able to do that. The whole act of playing my own music was such a huge step that I waited a really long time. I was listening to it, just myself, and I was like, “I know I have something to give.” And then you start giving and it starts perpetuating itself.

LIZ: But then your audience is like little baby birds going: “More, more, more!” There’s probably something more essential and archetypal about what you give in songs that people want, but if you hear all those different voices — “Lou, when you did this it was fantastic!” “Lou, when you did this it blew my mind!” “I can’t believe how much it touched me when you said this!” — it’s all these different mouths to feed…

LOU: Do you still keep making music when you reach that point where you’re like, “This is the most absurd thing?”

LIZ: Remember how you said you were absorptive instead of reflective? You tend to be someone who took everything in, sat quietly and watched everyone doing what they did? You’ve absorbed it all — now what you’re hearing from people is so harrowing to absorb that you can’t do it anymore. So commodization is the process of being eaten alive, more or less. There was just one or two people you were saving up all your songs for. Then suddenly there are like 30,000, and you’re dimly aware of it.

LOU: But you’re still concentrating on those one or two people anyway.

Lo-Fi, Take 3

LOU: I figure I could never walk into a studio and sit down and work on vocals and lyrics that meant that much to me. I have to be totally alone. I think in order to find your own identity and sound in a world like this — a world that is constantly bombarding you with the idea that you are not original and there’s nothing you can do to be original — the best thing you can do is somehow cut apart all the rock myths and offer your own rearrangement of them. What four-track and lo-fi meant for me was crafting the way I was going to speak and the words that I wanted to say. And it’s something that will just keep evolving. It’s not something that I’m attached to. It’s simply a recording technique.

LIZ: I’ll betcha. You pay me $50 if in five years you don’t change your mind.

LOU: About what?

LIZ: About recording — that it’s just a technique. I bet it means something more to you. Betcha.

LOU: Hmmm. More than a technique. But it’s a technique that I would probably always come back to, ’cause it means a lot to me.

LIZ: But you just said it didn’t mean anything.

LOU: No, I’m just saying — what I’m trying to say is, um, you’re right. OK. But I’m trying to devalue the whole lo-fi thing. I just hate that it means anything. I hate that there’s music that’s described by the way it’s recorded. That, to me, is just a total violation.

LIZ: I totally know what you mean. The radio will only take certain kinds of arrangements as legit.

LOU: But that’s not my problem.

LIZ: But it is your problem. It’s completely your problem.

LOU: No, it’s not, because I’ve been able to do so much already. I’ve already satisfied all of my artistic goals. All that’s left are just vanities. Otherwise it’s like, “Wow, I’ve been able to make music!”

Integrity

LOU: So you’d definitely be into being a huge star?

LIZ: But I’ve always craved my privacy. I think I’m at a great point now. I think this is the point at which I can indulge my ego in feelings of famousness, feelings of fabulousness, without really having to take the knocks for walking down to that shitty beer garden and having everybody know who I am. No one has told me where I can’t go. And no one has told me I’m only this good. They’ve said I could be the fucking best. And people still don’t know who I am. When I get really crowded in, it makes me feel miserable. I cry, I feel horrible. I feel like I have rotten self-esteem. Like I’m really ugly, really stupid and self-centered. It’s a drag. So I think being mega-famous would truly be a painful transition.

LOU: I still don’t have to worry too much about that. It’s just a total oddity for me. This is the first time I’ve been able to shamelessly throw myself into the media loop. Before, there was too much of this white-boy, punk-rock guilt factor. Now I don’t give a shit. There’s so many things in the world that’s so much more mediocre than what I’m doing, so why not toss what I have out and see how many people take it? There’s not a question of integrity involved.

LIZ: I could explain it in concrete socio-economic terms, in terms of how my family mistrusts my motivation, how I mistrust everyone I know, or how I no longer have a sense of identity. I don’t know what I am anymore. All that stuff really takes a toll on your ability to live.

LOU: There’s so much I’m not willing to lose. The one thing that I fear is becoming alienated from people you know, like your friends and people you love.

LIZ: Just like a Vietnam vet. Joan Rivers once referred to people who were not in the entertainment business as “civilians”. You know what I mean? Let’s face it, I’m well on my way to being a star. I was on the cover of Rolling Stone. But I don’t talk about all this with my friends. I want desperately to have people to talk about it with. And you just can’t. It’s one of the loneliest jobs at some level, because to all the people I love, I just live this entire existence like I don’t do what I do. I just go along with the people I’m close to as though it was the same old me. But clearly things are totally weird.

LOU: And you don’t talk about music? You don’t talk about where you have to go and shit like that?

LIZ: Where I have to go or what it was like to pose for Sassy — we really don’t talk about it.

LOU: Really?

LIZ: Really.

By John Corbett

Option, November/December 1994