By Rachel Brodsky

Spin, April 8, 2015

Liz Phair is suffering from a cold. “Does your head hurt, too?” she asks right before we hang up, referring to my own congestion. It’s understandable that the indie-rock torchbearer would be worn out after an hour-long phone call, sick or not — she has a lot to say. And though her (many) stories — which include names like SPIN founder Bob Guccione Jr., singer-songwriter Ryan Adams, and the inimitable Kim Gordon — support her Music Icon status, Phair only refers to herself in the most non-glamorous terms. “I live my life from inside me, so I don’t wake up and think, ‘I’m Liz Phair,’” she says.

Impressively, the pragmatic Phair has stayed sane despite some particularly noxious reactions to stretches of her 20-year catalog. Disciples and latter-day skeptics alike universally regard her debut album, 1993’s Exile in Guyville, as a glass ceiling-shattering compendium of lo-fi feminist thought; but the 47-year-old has endured plenty of venom from “sellout”-crying, so-called superfans who disregard everything she’s released since 1998’s criminally underrated whitechocolatespaceegg. (The revolt really began after her self-titled, major-label effort from 2003.)

Today, though, many guitar-toting, would-be contemporaries (Waxahatchee, Courtney Barnett, Girlpool) have taken her lead with starkly honest, plainspoken confessionals of their own. With the current generation of alt-rock apostles following in her stead, Phair hopped on the phone to rehash the earliest moments of her career, the state of gender inequality, and what she’s planning to do next.

Do you remember when Exile in Guyville topped SPIN‘s ’93 albums list?

It was a really nice feeling. You live your life, and every once in a while something comes in that gives you a different perspective on what you’ve done and what it meant. I don’t know how to describe that feeling. I live my life, and there are moments that I’ve been really lucky to have done something that meant something to people. It’s kind of like, “Well, damn.”

How did your professional life change after Exile?

It was part of the whole overwhelming-ness of it. I don’t know what I expected back then. At the time, I was trying to prove myself to a much smaller group of people who lived in Chicago, who didn’t give a shit. I was ambitious, but it was on a much smaller scale.

I did not enjoy that year at all, really. I had never performed live — that was another big problem. I put out the record before I had any stage experience whatsoever. Suddenly everyone was looking at me, and I was trying to get out there onstage and deliver something resembling what people were attracted to, and I was failing and it was really brutal.

I remember [SPIN founder] Bob Guccione Jr. took me to a ball game, and I didn’t realize that I was supposed to be his date. Like, I was doing a lot of different stuff. We went with people anywhere and everywhere, and it was weird because everyone was treating me in a very weird way. It was one of the days when I first realized that this had gone beyond anything that I could comprehend. Everyone’s eyes were following me and watching what I was doing the whole day. Everywhere I went, doors were opening, and people were just like, “Oh, it’s Liz Phair.” I’d been living this tiny little Wicker Park existence. It was a huge change. That was one of those days when I really got it. I was like, “Holy shit.” I don’t remember feeling anything good or bad, I just felt weird.

Do you think any contemporary musicians have had that same kind of sudden fame you experienced?

Bon Iver had that happen. He was up in a little cabin. I’m sure he was ambitious. I was ambitious, but I don’t think that having ambition necessarily prepares you for what happens. You have an idea of what you want to conquer, and it’s much smaller than what ends up happening. I mean, I don’t really know Bon Iver’s story, so maybe I shouldn’t use him as an example, but I do like the idea because I can relate to that — that he was isolated, trying to make this possible, but then boom, he’s a public figure. I felt that myself. I was a very introverted person when it came to my art. I was a bedroom guitar player, and it’s a totally different thing to go out and represent the new big thing in the public sphere.

What aspect of fame did you feel the most uncomfortable with, other than performing live?

It was really depressing in photo shoots. I felt so violated. I remember tweeting about Kristen Stewart saying something really dumb, like, about the press and feeling like she’s getting raped, which is an awful misuse of language. What she meant was what I felt acutely in those first few years — that your personal space has been annihilated. I mean, I would go to photo shoots and people would be putting on a party. They’d give me nothing to wear. Like, I was supposed to be naked because I had these few sexy songs. And all of these assumptions being made about me just felt so violating. It would’ve made sense if you had dropped that record on Oberlin, say, in ’93. But you drop it on mainstream and they didn’t understand who I was and where I was coming from. “Well, she’s the blowjob queen.” That’s what I became, the blowjob queen.

It’s awful that when a woman expresses sexuality, the mainstream accuses her of acting slutty.

I remember going to a wedding that year. I grew up on the north side of Chicago, and that’s a very preppy, conservative environment, and I never dreamed they were going to hear this record. I thought a bunch of indie people downtown might hear it, and then I get to this wedding, and somebody took me aside and they were kind of vicious about it.

She was like, “Are you going to sing at your friend’s wedding?” And I said, “No, I’m not here to sing, I’m here for the wedding.” And she was like, “Oh, you’re not going to sing?” She got all confrontational, and had this look in her eye like, “Oh, you live a double life, don’t you? You seem like a double-life kind of person.” All the art that I thought that I was playing with and playing against was gone. This was just a woman coming out and breaking taboos, but no one in the mainstream thanked me for breaking them. I don’t understand how our society cannot incorporate a woman’s right to be human.

There’s a super-sexual line in “Why Can’t I?”: “We’re already wet, and we’re gonna go swimming.” Funny how when that song came out in 2003, your early audience wanted you to stay frozen in your ’93 persona, when such frankly sexual lyrics appear all over your discography.

I think you’re right. I bought everyone’s backlash about Liz Phair. I mean, I kept doing interviews and trying to help people through it therapy-wise who were upset or felt a betrayal — I do get it. At the same time, I understood where I was coming from. I had been dumped onto a major label by my indie label; I never actually really signed with them. Suddenly I was in a major-label environment, and it was sort of sink or swim. So I was like, “OK, I’ll swim.” But there’s definitely me still in there. There’s definitely my rebellious, provocative self and honesty, but there is a lot of pop crap, too.

I was like, “Okay, now I have to be pop. How would I be pop?” I have no problem working in all different ways musically. If you met me, everyone’s like, “Oh, you’re so normal.” And I am. I’m not obsessed with my own image, and I like to play with it when it comes time to play with it, but I don’t live like, “I’m Liz Phair,” which is a good thing, but it’s also a bad thing in that I might not catch how it’s going to be viewed on the other end to the customer.

Yeah, if there’s anything that hasn’t changed much between ’93 and now, it’s that society chafes at the idea of women being sexual.

They cannot wrap their heads around something — women having sex — that is natural and has been in effect for hundreds of thousands of years. It’s about control. It’s disturbing to me that in my lifetime, I doubt I’ll see what I would consider the natural way to look at women as equal.

The idea of “control” reminds me of your opinion piece on Lana Del Rey in the Wall Street Journal. It seems like that’s what you were saying there, too: that men are writing the rule book for how women should be, even today.

I completely responded to Lana Del Rey’s persona. Why do women have to be perfect to get this honor [of performing on SNL]? Think of how many thousands of bands flew through SNL. I can think of tons of times I’ve seen an SNL performance where the music was kind of lackluster. Lana was really crucified. They literally acted like she had to deserve it. That’s so offensive. When Bright Eyes first got onstage, he wasn’t nervous? I’m sure he was, and yet everyone would just be like, “Oh, well.” It’s such a double standard.

Does it rankle you when people just want to focus on one specific time in your life, i.e., the Exile years?

No, I don’t mind bad reviews, especially if they’re smart and funny. I like a piece of art in any form. What rankles me is when I see someone’s issues — their own issues — getting dumped on me. Again, that’s probably the feminist in me. If it’s poorly written, and it’s clearly their issues coming through, that will really get me hot under the collar. I’d rather get a bad review by a great writer who’s intelligent and understands what they’re doing. Like, the zero out of tens are kind of funny. I don’t think I’m a misanthrope. It’s hard for me to deal with people who judge or have an impact who don’t understand what they’re talking about.

Are there any albums from the ’90s that you still go back to?

That’s really funny that you ask that because I’m in music and I listen to it all the time, but I don’t listen to it for the same reasons. That’s why I was always a round peg in a square hole. I spent my entire career that way. As much as I was in the indie world and I loved going to the shows, music also serves an emotional purpose for me. I’m not one of those people that make lists of bands I listen to and what genre. I think a lot of indie hates on that. For me, I’m like, “I’m feeling this way, or I need to cry.” I’m into the stories, the vibes of the sounds. Music takes me back to a place in my life — it connects me to my past. I go back to Pavement’s Slanted & Enchanted, Galaxie 500, early PJ Harvey, the Pretenders…

I’m constantly listening to music. This has been going on for 23 years — does that make me a music person or not? According to the indie law, I’m not; I don’t know what I should know. I’m not an expert. At the same time, I listen to music constantly and I like it, so am I or am I not? It’s funny, I think I am, I consider myself one, but according to their law, I’m not.

Are you working on any new material?

I am, and I had started one with Ryan Adams, but it never got off the ground. We had different ideas about how to record it, so that just kind of went unlogged. I’m very excited because my son is about to graduate high school. I’ve spent the last couple years just being the mom and took a day job doing television composing. I recorded a lot when he was young, and it wasn’t great for him. The minute you have your child doesn’t make you a great mom. You have to learn how to be a great mom. He flourished when I was around more, when I was mom-ing, so that’s what I’ve been doing.

I’m totally about getting back on tour. I feel like we’re both launching, because he’s excited too. We’re both able to lift up and decide where we are going to go and what we’re going to do. I can travel, I can tour, I can go back to being an artist. Everyone’s like, “Hurry get it done,” and I get that, but at the same time I’m finishing something that’s very me, and it’s on a natural time scale.

In general, do you feel like female musicians are being treated better than in the ’90s?

I don’t know how they’re being treated, but I’m always looking online for new artists to watch. If they’re women, I pick them out. They scare me because when I was coming up you didn’t have to be an amazing guitar player and an amazing songwriter. I just hacked my way through guitar playing, and I wrote, but [today’s female musicians] are turning over their keyboards in the middle of a song and creating a loop, like, going back to their amazing guitar-work while singing a song that they wrote. I get a lot out of younger female artists’ songwriting-wise. I find it very inspiring, more so than male artists right now. I’m obsessed with women in their early twenties.

Is there anyone in particular that you’ve been listening to?

Emily Greene and my friend Lena Fayre. She’s just so unique with her voice. I’m having fun finding the people who haven’t quite fully launched. I think that’s what I want my next period to be. I’m getting energy from that, and it’s made me think about what I want to do next.

You reviewed Keith Richards’ memoir a few years back. How did you get into book reviewing?

That was really fun and crazy because I had to do the whole review on tour. They sent me the only copy, and it went to the wrong hotel in Vegas. We were freaking out because we didn’t know how to get it. Then I had to write the review. I think I did six rewrites, and I lost electrical power. So I’m sitting in the driver’s seat with a little overhead light and all these wires are running out of the truck, and I’m finishing this review for the New York Times. It’s not very rock’n’roll, but nobody knows that story. Now I’ve been working on my own book. That’s something I’m enjoying quite a bit.

Is it fiction?

It’s fiction — not a memoir. Most music people do memoirs, but I decided my time was better spent writing fiction.

Speaking of memoirs, did you get a chance to read Kim Gordon’s?

I read an excerpt and it’s awesome. Sonic Youth was something that made me go to shows, and before I had a music career at all she was an obsession of mine because she was this cool chick. She was clearly from an art background, and she was nothing like me — she was way cool. She was definitely someone from the beginning that I really admired and held up as someone in a very male environment that shone and had a lot of presence.

What do you think of the fans who argue that Kim should have waited longer after her divorce from Thurston Moore to write this book?

I’ve read excerpts that had to do with him, and it doesn’t feel like raw anger at all. It’s clearly from her point of view, but why shouldn’t it be from her point of view? I will put money on this: I don’t think she’s doing it to bash her child’s father, but she is going to tell it like she saw it because it’s her chance to have her say. Just like me saying I’m waiting for my son to get out of high school to go on tour — her getting divorced gave her the motivation to write the book. I think that’s how you should deal with a breakup: Make art out of it.

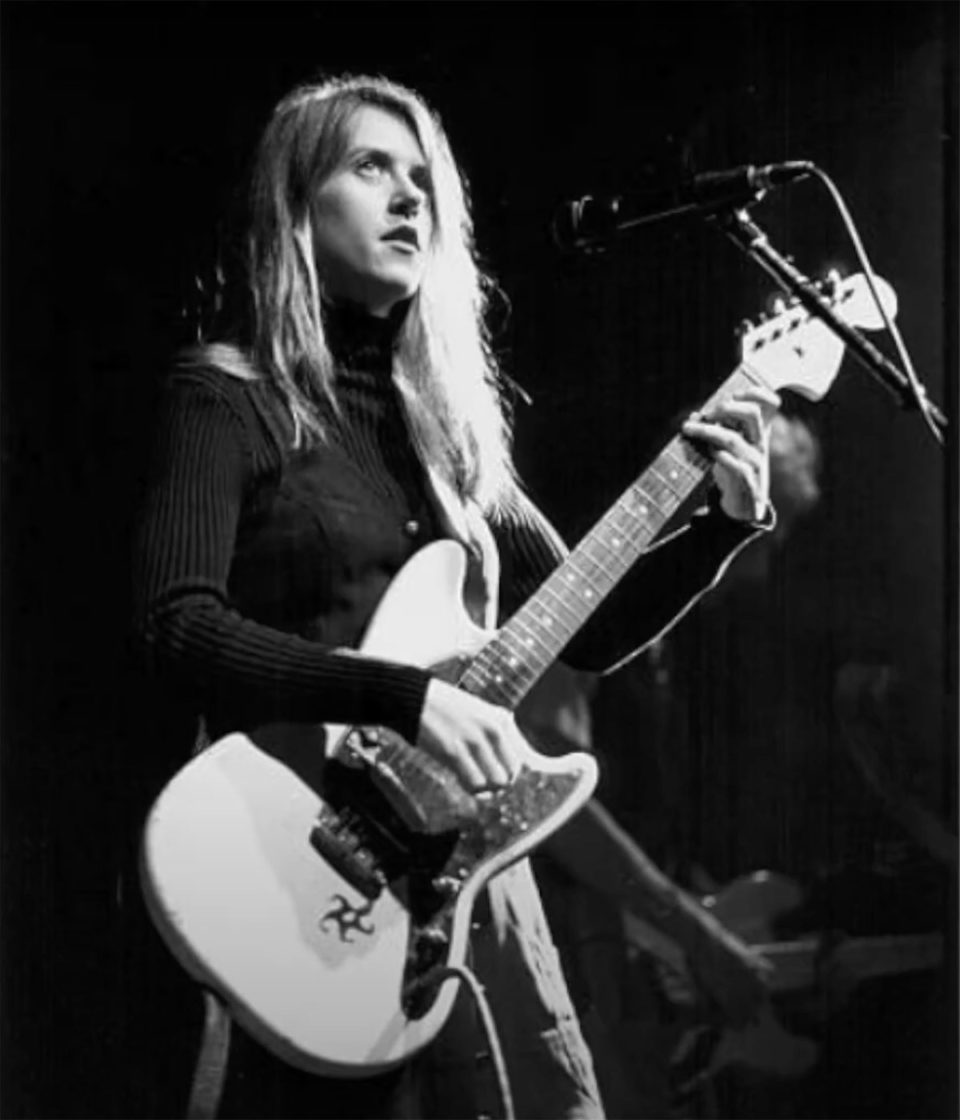

Featured Image: Liz Phair performing in 1994. (Photo courtesy: SPIN)