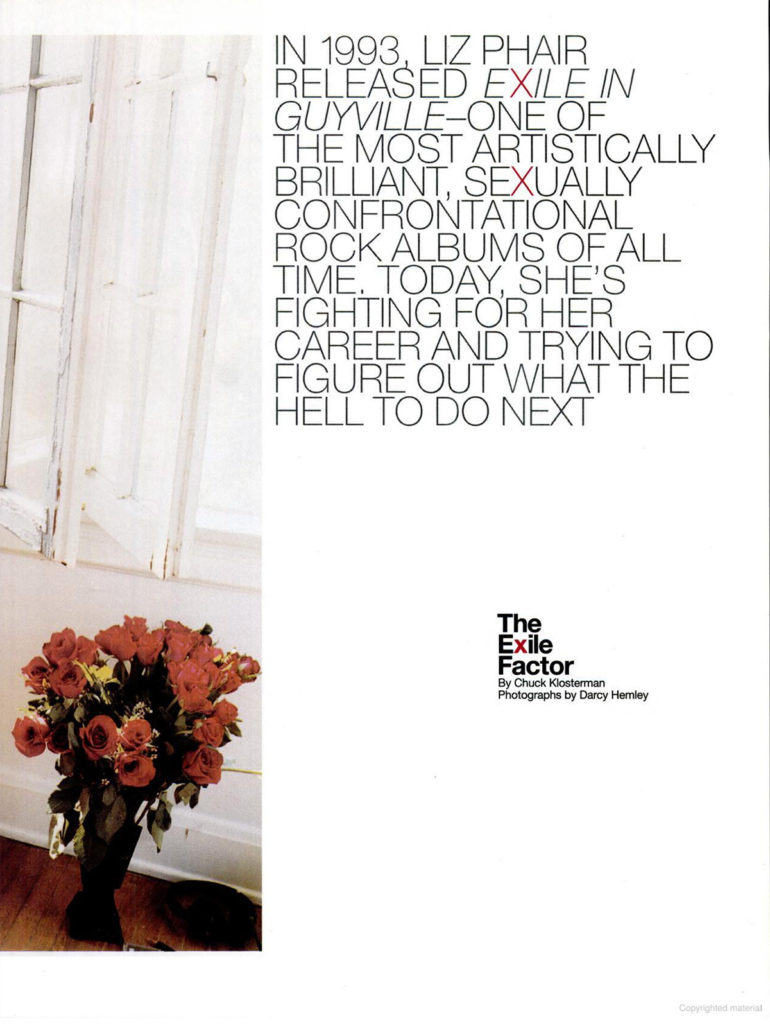

By Chuck Klosterman

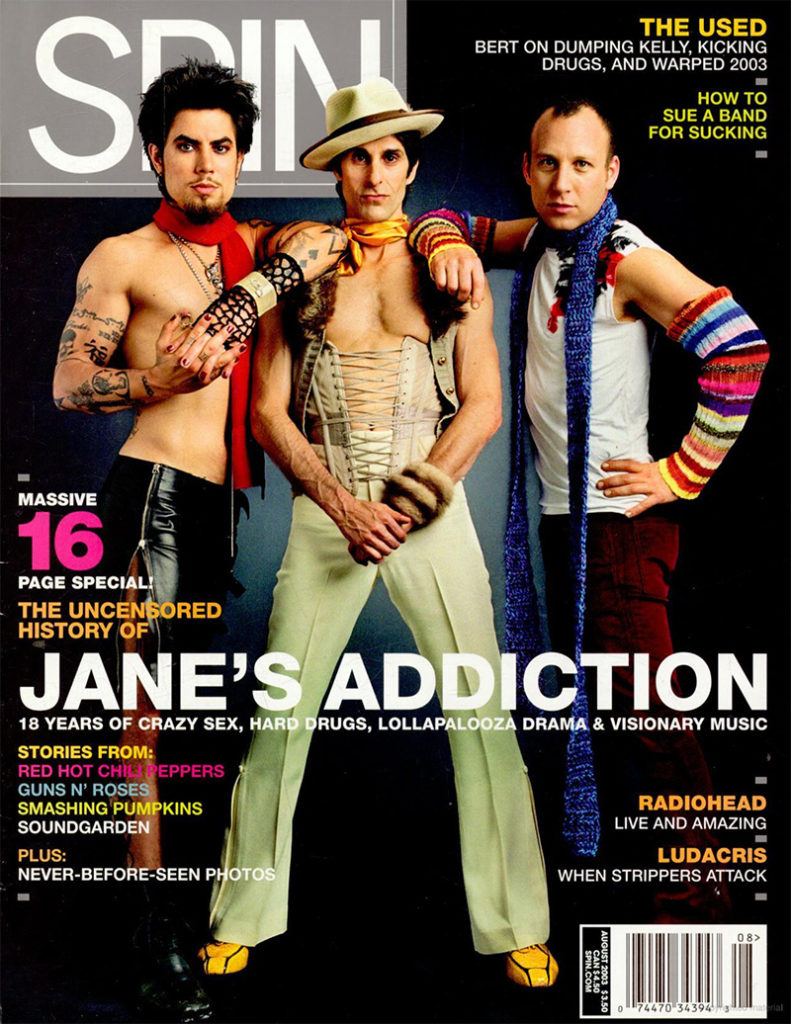

Spin, August 2003

Ten years ago, no one embodied postfeminism better than Liz Phair. 1993’s Exile in Guyville — arguably the most important record by a female singer/songwriter since Patti Smith’s Horses — reinvented the landscape of rock sexuality; Phair’s songs were indie-rock letter bombs, full of relationship trash talk, messy vulnerability, and foul-mouthed come-ons. For a moment, it looked like Phair was going to change the way rock fans thought about everything — especially what it means to be a female singer/songwriter.

Unfortunately, this did not happen.

Phair’s next two records met with mixed response from audiences and critics. After 1998’s Whitechocolatespaceegg, Lizzie disappeared into the sun-bleached wasteland of Los Angeles, emerging only for the occasional Gap ad or Sheryl Crow collaboration.

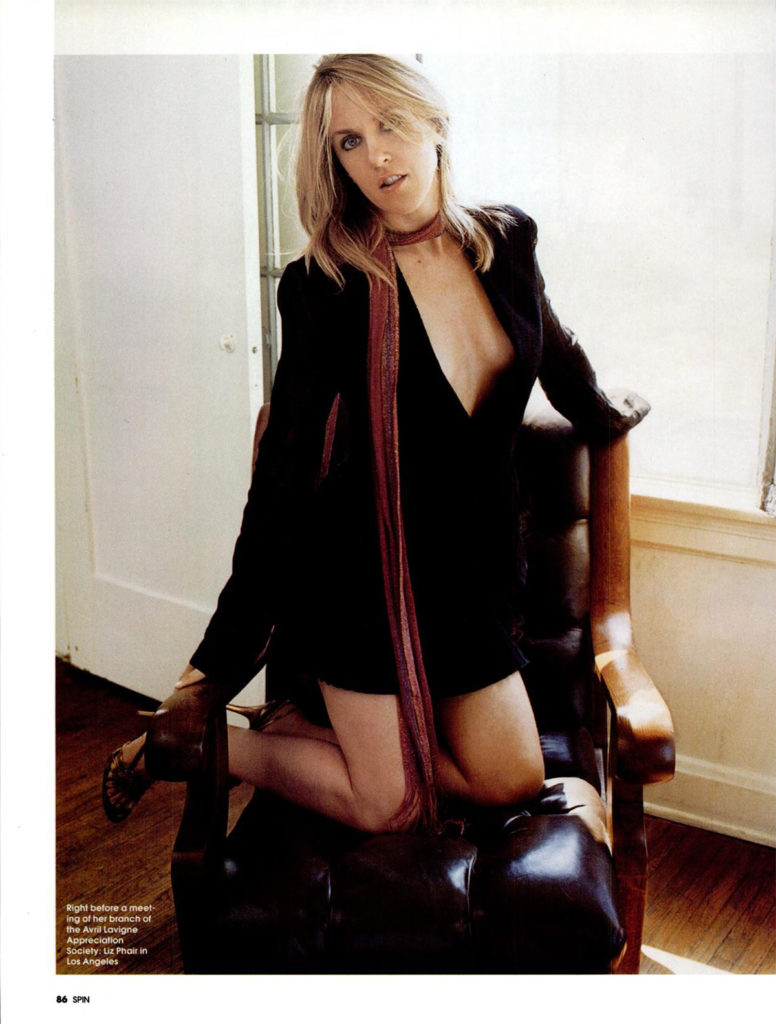

But now Chicago’s beloved “blowjob queen” is back — and this time, she’s ready to be famous for real. Her new self-titled album features contributions from unlikely sources (notably the hit-conscious songwriting trio the Matrix, best known for their work with Avril Lavigne). For the first time in her career, Phair has released an album overtly designed to make radio programmers dance on the ceiling. And even though she’s now 36, Ms. Phair can still bring the pain: She showed up at our interview wearing the most distracting denim miniskirt I have ever seen. I’m not sure if our conversation was earthshaking, but it certainly made me nervous.

Spin: What exactly have you been doing for the past five years?

Liz Phair: I’m getting used to this question. Right after being on the road with Whitechocolatespaceegg [in 1999], I started doing demos with my touring band in L.A. We tried [unsuccessfully] to get off of Capitol Records. That took maybe a year. Then I got divorced, so it took me six months to deal with that. I moved to Los Angeles with my son [age six], and I started songwriting with [Natalie Imbruglia collaborator] Gary Clark. I was also recording with Walt Vincent, who is Pete Yorn’s buddy. I did some recording sessions with Michael Penn [a veteran L.A. tunesmith best known for his 1989’s hit “No Myth”], and then I did some recording sessions with the Matrix. But it was just never the right time to release anything. At one point, the album was supposed to be finished entirely, but it didn’t have the hit single the label wanted, and I thought some of my older material needed to be represented. So I finally went through all those old recordings and culled the best stuff.

It seems like you’ve made a massive philosophical change regarding how you want your music to sound.

Not really. Maybe I have from your point of view, but to call it my philosophical change would be a misnomer. My music is still just me and my guitar and my piano. I write the songs small, and then you can produce them any way you want. I realize I was closely associated with a certain musical style early on, but I was always at war with the whole indie scene.

What was the war over?

I was basically saying, “Fuck all you guys,” and they were like, “No, fuck you, Liz Phair,” and I was like, “No, fuck you!” That’s what Exile in Guyville was really about. Everyone in that scene thought I was too suburban and liked mainstream music too much and never cared who was in Green River. All my boyfriends were big music heads, so that’s how I acquired good taste in music — but I always liked radio songs. They’re all purists in the indie world, and I hate that.

But aren’t you worried that this record will end up somewhere in between those two worlds? What if this glossier music alienates all your old fans, yet never appeals to mainstream radio listeners?

I really, truly do not worry about that. I’m not concerned about that kind of approval anymore. Yes, I’d like to reach a wider audience. Yes, I’d still like to bring something worthwhile. But after I had my son, everything [about what I wanted to do musically] changed. You know, my last manager desperately felt the same way you did and never wanted me to chase a hit — that’s something we talked about for a year. But the truth of the matter is that I listen to the radio, and I always have.

Do you feel haunted by Exile in Guyville? Do you feel like that record will define you forever, regardless of whatever else you produce?

I used to feel like that. I thought I could never measure up to Guyville. I kept trying to make a record as good as that one. I thought about that a lot. But here’s the funny thing: In 2000, the rights to Exile in Guyville reverted back to me. Someone [at Matador Records] forgot to put it back on the books and lock it up for 30 more years. And suddenly, once I owned it, I felt very differently. I was really glad I made that record, and I no longer felt like I had to make that record again. When I made Exile, I was a collegiate art major who had all this brain power and nothing else to do, and I could direct all my energy into one project. I didn’t have a job or any responsibilities.

On that first record, it seemed like you were looking for an incredibly complex — and therefore potentially transcendent — romantic relationship. But on the new album, you sing about dating some young, dumb guy who plays videogames all day.

I don’t need to get my identity from a man anymore. When I was younger, I took my identity from a man anymore. When I was younger, I took my identity from being in love with someone else. And love can be transcendent. But let’s face it: I’m a lot older now; I have a kid now. Your priorities change. Everything else just seems like gravy. I mean, I’m glad there’s great literature and great art, and I’m glad I was able to contribute to that, if I did. But right now, in my life, I just need to rock.

Do you every exaggerate your interest in sex for artistic purposes?

[Pause] I definitely will do that on occasion. I exaggerate lots of things in songs. But I am kind of known — at least among my friends — for always thinking about sex. It drove my last boyfriend crazy. He was like, “Everything is always about sex with you.” But I mostly just think about it — I don’t act upon it as often as my songs suggest. I think I’ve been a very well-fucked woman. I’ve had my fair share of dalliances. However, I need to connect with the person. I’m not a one-night-stander. And once I’m in a relationship, sex is a big part of it.

I’ve been listening to all four of your records this wee, and you’ve evolved a lot. But the one thing that seems to have remained constant is your interest in what one of your new songs, “H.W.C.”, refers to as “hot white come”.

I think it’s gotten better. Sex, I mean. I enjoy it more now. I’m not as threatened by the power relationship of sex as I used to be. And I choose who I have sex with wisely. [Pause] Well, actually, let me take that back. I don’t always choose wisely.

It just seems to me that early in your career you were one of the few people who really talked about sex honestly and insightfully. But on this particular album, your use of sex feels more sensationalistic and maybe a little less sincere.

I have to disagree with you. A song like “Little Digger” is about my son catching me with a man, and there is a lot of serious discussion about what that means. And how the sex I’m sometimes so cavalier about has devastating ramifications on other parts of my life. As for the song “H.W.C.”, well, you’re just going to have to trust me when I tell you that song was written purely. That was just me, in Chicago, with nothing going on: no one was calling me, and nobody cared about Liz Phair. So I wrote a song in my loft about a feeling I had with someone that I had never experienced before. I think your problem with my new material is that it’s less confessional.

I would probably agree with that.

The thing is, I was stoned a lot when I made those early records. And life has more to do with the face value of reality when you’re not stoned. That confessional stuff you liked so much — that was really just the sense of intimacy I was known for. I would practically bring you into my own bed. I was kind of like an actress who would let herself be ugly and unfiltered on screen. But now I’m more like a leading lady going through the motions with the right lighting. Is that a good analogy?

That’s a perfect analogy. But I find that sentiment depressing.

Really? That bums me out. I know exactly what you’re saying, and I understand entirely, but to hear you say it’s depressing makes me kind of sad. I don’t know why you should be depressed. Do you feel like you’ve lost someone who could make you feel that way?

No, that’s not it. It just seems like you’ve made this decision to —

You keep saying this was my decision. It wasn’t a decision. Those songs just aren’t there anymore. I’ll let you go through my demos and look for them if you want. I think this record is depressing to you because it makes you feel that you’ve lost part of your own childhood, and you realize you can’t get that back. But I can’t make a 25-year-old’s record at the age of 36. For me, it boils down to this question: Do I want to seem authentic, or do I want to feel authentic? And I choose feel?

That’s a totally acceptable choice, but as a consequence, do you think this record is less profound than some of your earlier work?

I don’t think so. I really don’t. But this is still the albatross of Exile in Guyville. That was really a profound album, and I’ve tried to capture that again. But I can’t do it. I’m incapable of writing that kind of album again. This record isn’t on par with Guyville. Whip-Smart wasn’t on par with Guyville, and Spaceegg wasn’t on par with Guyville, either. I can’t make that genius thing again. But this record still moves me. It’s profound to me. I think you and I might have been a the same point when I was 25, but we have diverged. [Laughs] I think maybe it’s time for us to break up.

What would bother you more: to wake up tomorrow and be half as smart or to wake up tomorrow and be half as sexy?

I’d rather be stupid and sexy. I know that’s wrong, but I think you can still be happy when you’re stupid.

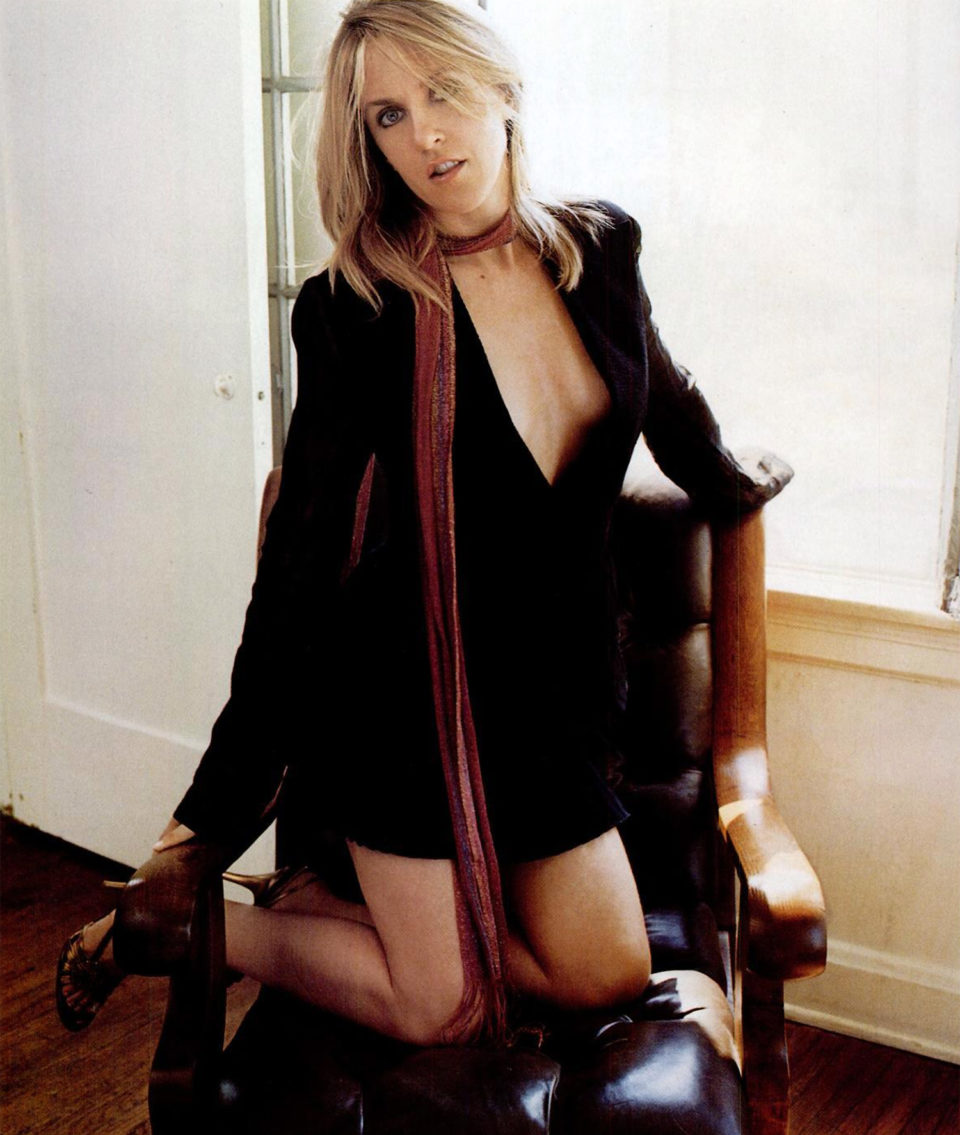

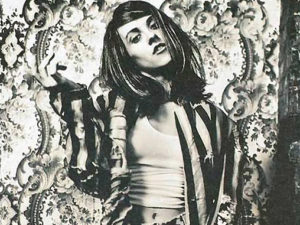

Featured Image: Liz Phair in Los Angeles. Photograph by Darcy Hemley.