By Mikael Wood

Los Angeles Times, May 24, 2018

Liz Phair had a good excuse for arriving late to an interview the other morning.

“I’m so sorry — I was at therapy,” the singer said with a laugh as she slid into a booth at a restaurant near her home in Manhattan Beach. “I’m trying to be proactive about my stage fright.”

An indie-rock star since her instant-classic 1993 debut, “Exile in Guyville,” Phair said she’d learned through experience to control an anxiety that goes back to her childhood. But now the fear was flaring up again ahead of a tour on which she plans to perform the songs from “Guyville” as they appeared on a series of homemade cassettes she released under the name “Girly-Sound” in 1991.

“Which means I have to remember to sing them slightly differently than I’ve been singing them for decades,” she added. “And it’s not like I’m gonna sit there with a lyric sheet. Lame.”

The tour, set to kick off May 31 with a sold-out show at Hollywood Forever’s Masonic Lodge, comes behind a new 25th-anniversary “Guyville” box set that includes the long-bootlegged “Girly-Sound” tapes along with essays and an oral history explaining the album’s importance and influence.

I wanted to take the perspective of the female characters in the Stones’ songs.

— Liz Phair

Very loosely conceived as a track-by-track response to the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main St.” — “I wanted to take the perspective of the female characters in the Stones’ songs,” Phair explains — “Guyville” captured the indelible voice of a brash and gifted young songwriter dissatisfied with rock’s domination by men.

The record was frank and funny and unashamedly sexual, and though Phair was pulling directly from her years in Chicago’s Wicker Park neighborhood, “Guyville” ended up resonating widely; today it’s still a touchstone for twentysomething indie rockers like Lucy Dacus and Soccer Mommy.

In addition to preparing for her tour, Phair, 51, is finishing a new album, her first since 2010, and working on a memoir she says will address her life as a musician and a mother. Yet she knows that “Guyville” holds a special place, which is one reason she seems to have spoken with every writer who expressed an interest in the reissue.

“The problem is, you do too many interviews and you end up kind of saying the same things again and again,” she admitted over fizzy Arnold Palmers. “I think this might be the last one for a while.”

Have you found that men and women ask different questions about the album?

Yes. Women want to talk about being female in the industry and being female in general — the 2018 women’s uprising. And men tend to be more focused on the Wicker Park scene and indie rock back then. Everybody’s sort of picking the movie that they get to star in.

The ideas people bring to you about what “Exile in Guyville” represents — are they in line with your own thinking?

It depends if you mean what I thought when I made it. At the time I was definitely feeling empowered, but I wasn’t feeling like part of a movement per se. I was just trying to make a sincere rock record from a female point of view: You’ve experienced it this way; now let me tell you the other side of the story.

By bringing attention to the “Girly-Sound” tapes, you’re doing the scariest thing a writer can do, which is to reveal your drafts. Why?

Because the songs have become fixed in people’s minds. I’ve always had a passion — maybe because my mom was a docent at the Art Institute of Chicago — to show how creativity works. To show that it’s a process, and that you too can do it.

How long had it been since you’d heard those early versions?

I listen to them a lot, actually. But I tend to throw stuff out, so I was really appreciative of the fan sites keeping this stuff alive.

Before this new set came out, you’d just Google “Liz Phair Girly-Sound”?

I still do that. I engage with myself probably the way a lot of fans do. I don’t have any record collection at my house. I use YouTube for everything.

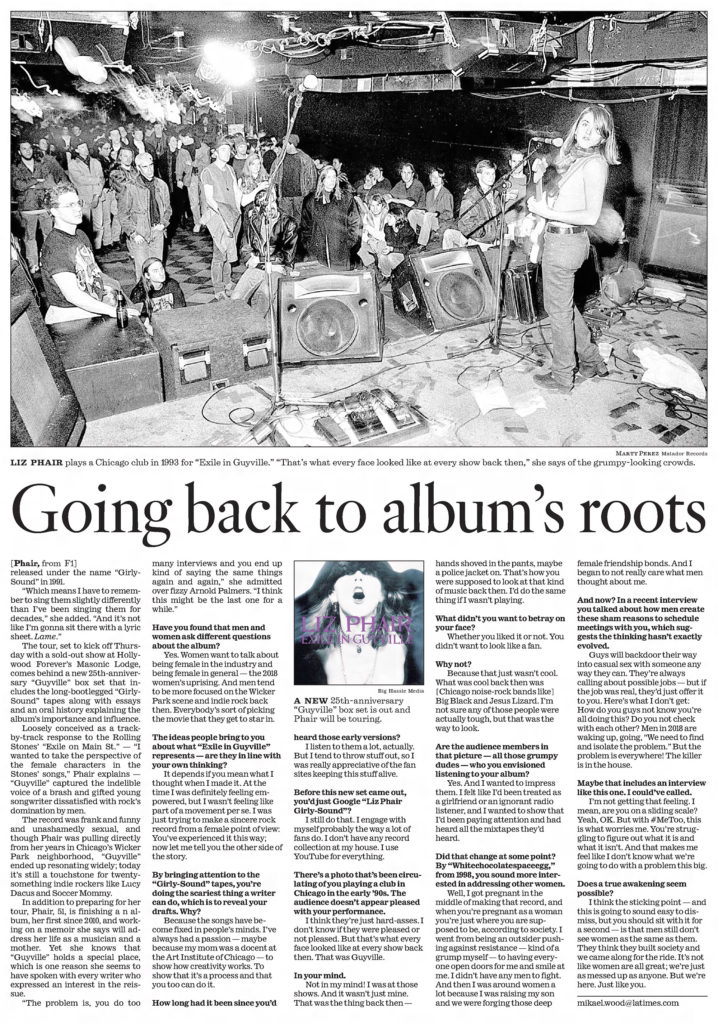

There’s a photo that’s been circulating of you playing a club in Chicago in the early ’90s. The audience doesn’t appear pleased with your performance.

I think they’re just hard-asses. I don’t know if they were pleased or not pleased. But that’s what every face looked like at every show back then. That was Guyville.

In your mind.

Not in my mind! I was at those shows. And it wasn’t just mine. That was the thing back then — hands shoved in the pants, maybe a police jacket on. That’s how you were supposed to look at that kind of music back then. I’d do the same thing if I wasn’t playing.

What didn’t you want to betray on your face?

Whether you liked it or not. You didn’t want to look like a fan.

Why not?

Because that just wasn’t cool. What was cool back then was [Chicago noise-rock bands like] Big Black and Jesus Lizard. I’m not sure any of those people were actually tough, but that was the way to look.

Are the audience members in that picture — all those grumpy dudes — who you envisioned listening to your album?

Yes. And I wanted to impress them. I felt like I’d been treated as a girlfriend or an ignorant radio listener, and I wanted to show that I’d been paying attention and had heard all the mixtapes they’d heard.

Did that change at some point? By “Whitechocolatespaceegg,” from 1998, you sound more interested in addressing other women.

Well, I got pregnant in the middle of making that record, and when you’re pregnant as a woman you’re just where you are supposed to be, according to society. I went from being an outsider pushing against resistance — kind of a grump myself — to having everyone open doors for me and smile at me. I didn’t have any men to fight. And then I was around women a lot because I was raising my son and we were forging those deep female friendship bonds. And I began to not really care what men thought about me.

And now? In a recent interview you talked about how men create these sham reasons to schedule meetings with you, which suggests the thinking hasn’t exactly evolved.

Guys will backdoor their way into casual sex with someone any way they can. They’re always calling about possible jobs — but if the job was real, they’d just offer it to you. Here’s what I don’t get: How do you guys not know you’re all doing this? Do you not check with each other? Men in 2018 are waking up, going, “We need to find and isolate the problem.” But the problem is everywhere! The killer is in the house.

Maybe that includes an interview like this one. I could’ve called you on the phone.

I’m not getting that feeling. I mean, are you on a sliding scale? Yeah, OK. But with #MeToo, this is what worries me. You’re struggling to figure out what it is and what it isn’t. And that makes me feel like I don’t know what we’re going to do with a problem this big.

Does a true awakening seem possible?

I think the sticking point — and this is going to sound easy to dismiss, but you should sit with it for a second — is that men still don’t see women as the same as them. They think they built society and we came along for the ride. It’s not like women are all great; we’re just as messed up as anyone. But we’re here. Just like you.

Featured Image: “I was just trying to make a sincere rock record from a female point of view,” says Liz Phair of 1993’s “Exile in Guyville.” (Photo: Jay L. Clendenin, Los Angeles Times)