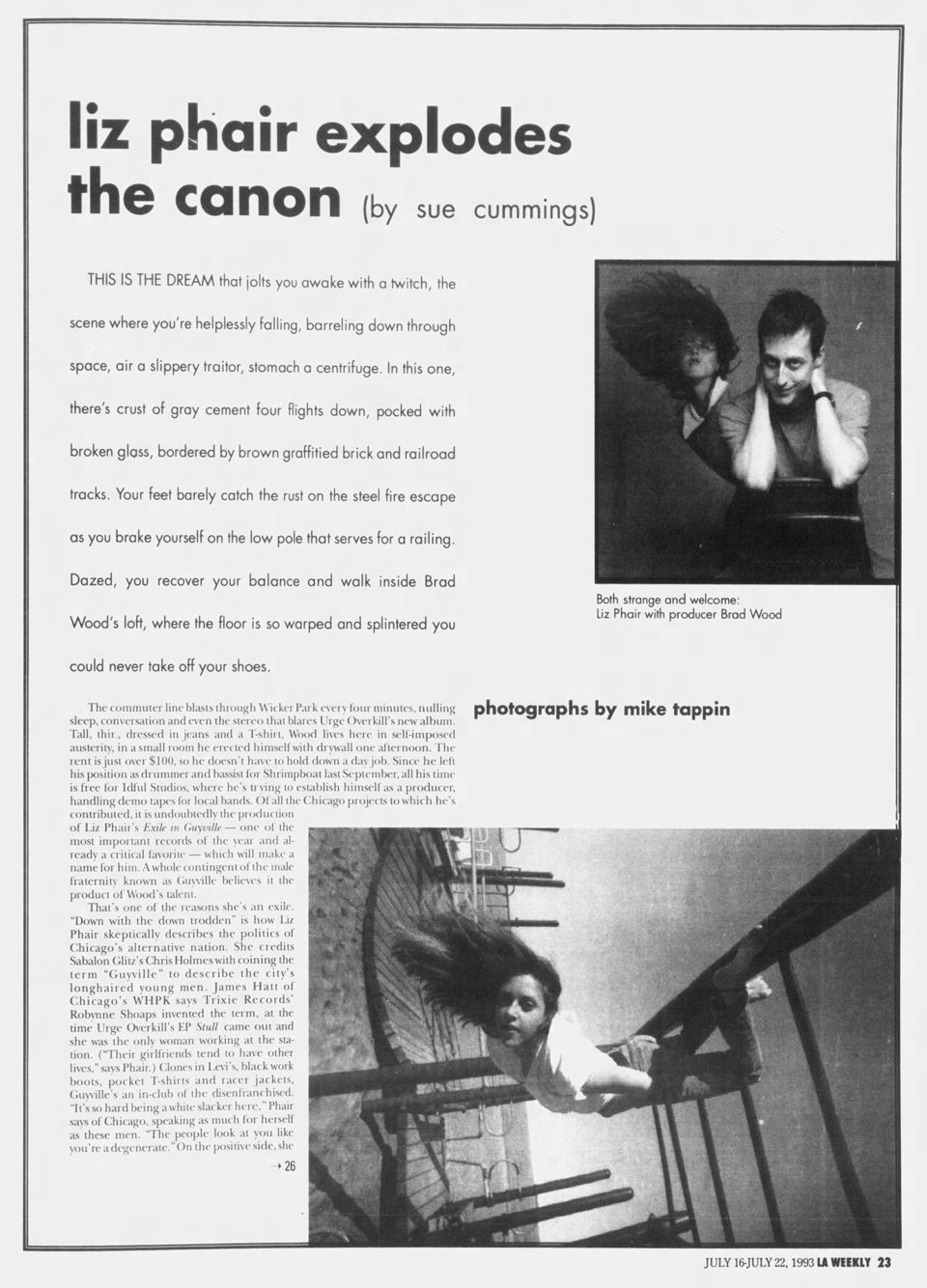

THIS IS THE DREAM that jolts you awake with a twitch, the scene where you’re helplessly falling, barreling down through space, air a slippery traitor, stomach a centrifuge. In this one, there’s crust of gray cement four flights down, packed with broken glass, bordered by brown graffitied brick and railroad tracks. Your feet barely catch the rust on the steel fire escape as you brake yourself on the low pole that serves for a railing. Dazed, you recover your balance and walk inside Brad Wood’s loft, where the floor is so warped and splintered you could never take off your shoes.

The commuter line blasts through Wicker Park every four minutes, nulling sleep, conversation and even the stereo that blares Urge Overkill’s new album. Tall, thin, dressed in jeans and a T-shirt, Wood lives here in self-imposed austerity, in a small room he erected himself with drywall one afternoon. The rent is just over $100, so he doesn’t have to hold down a day job. Since he left his position as drummer and bassist for Shrimpboat last September, all his time is free for Idful Studios, where he’s trying to establish himself as producer, handling demo tapes for local bands. Of all the Chicago projects to which he’s contributed, it is undoubtedly the production of Liz Phair’s Exile in Guyville — one of the most important records of the year and already a critical favorite — which will make a name for him. A whole contingent of the male fraternity known as Guyville believes it the product of Wood’s talent.

That’s one of the reasons she’s an exile. “Down with the down trodden” is how Liz Phair skeptically describes the politics of Chicago’s alternative nation. She credits Chicago’s alternative nation. She credits Sabalon Glitz’s Chris Holmes with coining the term “Guyville” to describe the city’s longhaired young men. James Hatt of Chicago’s WHPK says Trixie Records’ Robynne Shoaps invented the term, at the time Urge Overkill’s EP Stull came out and she was the only woman working at the station. (“Their girlfriends tend to have other lives,” says Phair.) Clones in Levi’s, black work boots, pocket T-shirts and racer jackets, Guyville’s an in-club of the disenfranchised. “It’s so hard being a white slacker here,” Phair says of Chicago, speaking as much for herself as these men. “The people look at you like you’re a degenerate.” On the positive side, she says, the network helps hold indie rock together. On the negative, Guyville has a party line as well as a dress code, and it fosters a perverse kind of elitism somewhat like the Marxists whose working-class idealization makes them snobs.

“Guyville takes itself very seriously and believes, more than anything, that it is bettering the social standards of our country,” Phair says. These men, usually musicians, are Phair’s friends, the ones she has dated since her art-school days at Oberlin College, where they shared the usual hipster alienation from their middle-class roots, as well as love for music. In her early 20s Phair played guitar and wrote to prove she was not their groupie but an equal. At 26, having just completed her first album, she has come to define herself against the norms of the club.

Phair started writing her album to communicate with an estranged acquaintance she won’t identify now, then decided to sequence the 18-song collection as a track-by-track mirror to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street. The record’s personal significance has faded, but it still answers her Guyville contemporaries, the masculine powers of alternative rock, and revises Main Street, which she spent months studying. “What I did,” Phair says, “was go through [the Stones’ album] song by song. I took the same situation, placed myself in the question, and answered the question. ‘Rocks Off’ — my answer to that is ‘Six Foot One’. It’s taking the part of the woman that Mick’s run into on the street. ‘Let It Loose’ — okay, that’s about this woman who comes into the bar, she’s got some new guy on her arm, Mick was in love with her. He’s watching this guy, ‘eh, just wait, she’s gonna knock you down.’ He’s talking, ‘let it loose,’ as if to be like, babe, what the hell happened, talk to me. So my answer was, ‘I want to be you…'” Phair sings the opening to “Flower”, probably the most explicit, pornographic statement of female lust ever written by a white American pop singer, delivered with a restrained, passive tone that dramatically undercuts its abandoned. The songs closes with Phair almost whispering, “I’ll fuck you ’til your dick is blue.” “I put a song in there that lets it loose,” she says.

Guyville, of course, turned out quite different from Main Street, and more original than most current albums that don’t, as Guyville does, footnote their inspirations. “Of course [the Stones’] positions were different. That album is about them dealing with their identities through the new eyes of their fame. Their album is far more musically expansive, intricate than mine. But I had to be true to my circumstances, when I’m a female singer-songwriter and I take a far more singer-songwriter approach to the structure.”

It doesn’t matter if her listeners think of Exile on Main Street, Phair says. “It really isn’t important to me to have done it, so I could learn what goes into a really great album. The structure gave me limitations. It gave me a universe within which to be as creative as possible because there were laws.”

Phair’s conceptualizing gives her work a handle, but what seizes you on the album’s first play is the simple production and her lyrics’ frankness. In the end, it will be hard for critics not to like her, because she has made a meta-album: a feminist critique of a standard in the boomer rock canon, a record that reviews another.

She has come home meaning to work in the garden, to pay off a debt she owes her mother. The house is surrounded with flowers they’ve put in, but this spring, her grandmother says, brought an unexpected gift. For the first time, in all the years of their residence, violets have spontaneously bloomed on the front lawn, speckling the broad swath of green grass with purple. It must have been the wind that planted them, her grandmother agrees: “After all, that’s what Chicago is know for.”

This isn’t Guyville. It’s a quiet and soft, an ordered nursery for children, a neighborhood of expansive houses imprinted by an era of hope if not certainty. The two-story colonials still hold firm, unweathered, maintained between curving streets named Maple, Spruce and Elder. Winnetka, Illinois, is a model in every way: for the postwar suburbs later built in its image; for its per capita income, the hightest in the nation until the late ’80s; for its public high school, Newtrier, whose customs formed the basis of the movie The Breakfast Club, written and directed by Newtrier graduate John Hughes. Winnetka is where Elizabeth Phair, a child adopted at birth, grew up. It’s the ex of her exile, the perfect home where she feels both strange and welcome.

“You don’t have to lock the car,” Phair says as we park in the driveway. “Thisis the land of complete safety.” Inside through the back door, in the room off the kitchen, is the family piano, a modest upright. On the refrigerator is a Chicago Tribune clipping of her father, Dr. John Phair, the AIDS researcher and chief of infectious diseases at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, standing next to Miss America in some photo opportunity. Beside it, from the same edition of the newspaper, is a review of one of Liz’s local performances. A handmade Mother’s DAy card bears a small photo of her mom’s face, cut and pasted into a drawn border. “Motherhood,” reads the caption, “it has its perks.”

Phair’s grandmother, Mrs. Zeller, greets us in an immaculate, fitted suit, her hair freshly coifed. She is visiting from “Cincinnatah”, as she says it. Mrs. Phair soon returns from a class she has led through the Chicago Museum of Art, and Dr. Phair comes home from the office. He pours himself and Mrs. Zeller a cocktail, and they recite to his daughter the messages that are coming in by the dozens from the music industry. Liz, ever the malcontent, has abandoned her city apartment in a dispute with the landlord over utilities, and Matador Records, frustrated with trying to track her as she drifts through friends’ living rooms, has resorted to giving out her parents’ number.

“Are you done with the video?” Dr. Phair asks as we settle into the living room. “We’re mixing it this week,” Liz says. “All the footage is shot, but I need to find one more image.” She runs upstairs to change for a photo session, to get out of the clothes she’s been wearing for three straight days. “Liz says she’s looking for a shot of ants swarming, something to indicate decay,” I say. Mrs. Zeller shakes her head, smiles, and wrinkles her nose. “Have you seen the video?” asks Dr. Phair. “She jumped into Lake Michigan, right into the water. It was under 40 degrees.”

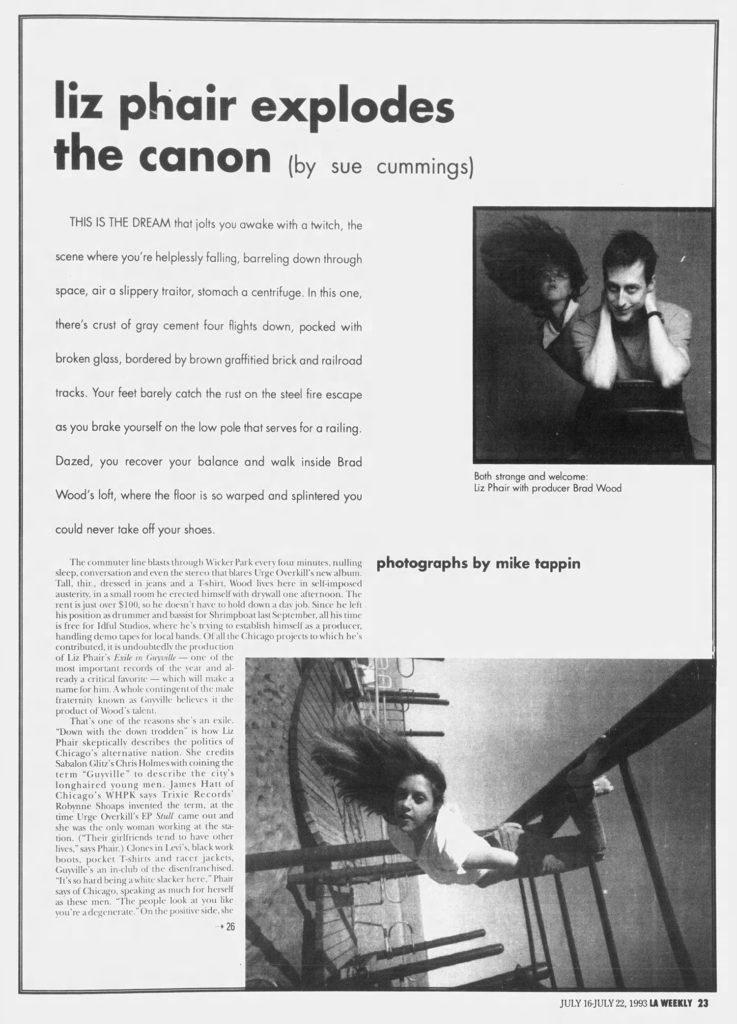

When the photographer arrives, Liz directs us to the beach for the session. She takes us right down to the water’s edge for pictures against the blue interface of the sky and lake. It’s a saavy move, one that will guarantee image continuity, because the shots will resemble the video to her first single, “Never Said Nothing”. Pouting and posing, then dancing, mugging, hanging by her trim, muscular legs on the bars at the beach playground, Phair changes with brief self-conscious flashes from suburban daughter to earthy pop coquette. She kicks off her clogs, tries on sunglasses, different coats, picks up her guitar, and duck-walks across the top of a wall. “Come here,” she demands, asking the photographer to imagine a shot she frames between her fingers. When the pictures come out, she’ll look like a babe, with her blond-streaked hair, her tanning-booth tan, her T-shirt knotted to reveal a peek of belly. She knows exactly what she’s doing.

“I’m topless on my album cover,” she says. “My parents don’t even know it yet.”

Phair’s place in indie rock is as conflicted as her album’s title. The low-fi production of Guyville defers to the same post-punk values her lyrics mock with quips about Galaxie 500 videos. Her sparse sound, dislocation and disregard for chops make her at home alongside Sebadoh on college airwaves, yet she steps in Joni Mitchell’s place to describe the particularities of feminine experience, recharging that genre with direct rage, sexuality and occasional saccharine sweeps that guiltily recall James Taylor. (Baby James is one of the first things Phair can recall practicing in her first sessions on a birthday-present guitar.)

Private and revealing, nearly embarrassing, Guyville is, in its emotional palette, almost the Pet Sounds of girl rock. Teenage boys might form a band to jam in the garage, but Phair is the mall rat singing acoustic confessions to bedroom walls. Yet she’s not passive. Sometimes the songs spill over with defiance, and the anger is no punk abstraction. The chorus of “Help Me Mary” rails against a gang of male friends who freeload in her apartment: “They play me like a pit bull in a basement/and for that/I lock my door at night,” she sings. “Johnny Sunshine” blows the whistle on a would-be lover and leaver: “He’s just a hero in a long line of heroes/looking for someone attractive to save… and he won’t leave town ’til you remember his name.” Phair is the female Paul Westerberg, who we so often assumed spoke for everyone. The most remarkable thing about Phair’s feminist answer is how it becomes the listener’s discovery, how you didn’t know those things could be said so well. She’s the Swiss Army Knife that does everything and holds an edge, and you didn’t know how much you needed ’til you got it.

In the next year, Phair’s greatest challenge to indie rock will concern the way it grants credibility to touring rather than videos or radio airplay. She hates performing; she cried over a Chicago daily review that panned her stage act for “incessant strumming”. “I started to play live because I wanted to prove I could do the dirty work. You feel like a show dog. I feel like a freak show.” As an artist, she says, “I’m used to being the manipulator, not the manipulated.”

“I love shooting videos, I loved making my videos. I got exiled from the indie crowd because I have a lot of mainstream trappings, a lot of obnoxious tendencies for the sake of reacting against indieness, embracing Diet Coke and beaches and convertibles.

“Guyville,” she explains, “believes in presenting a better model for how you treat people, what you’re interested in, the kind of music you’re listening to. Quality is of the utmost importance to these people, but quality began to equal obscurity, and that’s obviously untrue.”

Her face fills the entire frame: it’s tilted sideways and with her mouth wide open, frozen in the box. When we return from dinner break back to the editing bay, the locked image of her head glares around the darkened room, cloned in exact copies on 12 other screens mounted into the walls. Phair and Katy Maguire, her video director, have spent hours at this console, playing, replaying, layering and discarding images of Phair shot for her video “Never Said Nothing”. They know every breath of the track as well as the letters of their names. When it’s done, the video will be only three minutes and three seconds long, a mere blip to viewers of MTV, but Phair and Maguire are drawing a flip book with 60-base mathematics. Three minutes in 180 seconds, 5,400 frmaes at 30 per second, and by the time they’re done, they’ll have considered every one of them.

On a side screen, Maguire punches up footage of Phair’s lip-synched shot in black and white to resemble strips taken in a photo booth. She spins the sequence backward and forward to get precisely the right frame, then locks it in and applies it over the color footage of the main take, a sequence of Phair dancing through a lush, blooming greenhouse. The photo-booth shot, says Maguire, mirrors the album cover; the progression of images echoes the psychological shifts of the song. “The concept of the video is going through the emotional changes of denying a lie, but the person still feeling they have the right to say or dow whatever they want. The photo booth is a stark contrast to the lush growth, so you get the falseness, that the song is really about duplicity. The photo-booth shots are obviously manipulative. So is a video, but people tend to believe that as real time.”

This is the first music video for Maguire, who recently won the best-of-the-festival prize at the Illinois Film Festival for her independently produced Primordial Protoplasm. Phair and Maguire have only known each other a few months, but they’ve fashioned a partnership motivated by feminist ideals and teamwork that gives Phair the technical support to execute her visual ideas. Maguire assembled a production crew largely composed of women; she hopes next time it will be all women. In a philosophy she compares to Spike Lee’s willingness to work only with blacks, she considers this affirmative action. They’re producing “Never Said Nothing” on a shoestring, but help from friends and donated equipment has made the results professional. It will be one of the few rock videos done this year by a female artist with strong visual concepts, controlled by a director who is also a woman.

Yet all this feminist purism will be lost on the video’s viewers, who’ll see Phair pout, smile and shimmy in a series of bright dresses, thrust out her breasts, swing her guitar, dunk herself into a lake and emerge with a wild hair flip. Phair and Maguire regard it all as a calculated ploy for a new artist, what they call “the meet and greet”, using sex appeal to get attention for a more challenging experiment next time. “I play girl,” says Phair, “I do stuff where I take advantage of traditional expectations of women…”

“Iconography is completely important, especially for women, because appearances are a large part of what women have been judged by. It’s what the rules arre. I want to build a career, I want to do that intelligently. I don’t want to play by the rules a lot of the time, but certain things I know to be a fact, in this case of how you gain public interest. Watch the political campaigns.”

“Liz looks cute,” says producer Dawn Rubin, as she and Katy play the rough edit all the way through with the song. Maguire laughs in agreement; Phair has gone down the street to get a soda. I sit off to the side of the console, as they watch Phair dancing in a blue silk dress, smiling; she leans forward and shakes her head, put her hand to her chest to catch her neckline just before she flashes her bra. “See, there she is going, no, I didn’t do it, I didn’t say it,” says Maguire. At the end of the sequence Phair thrashes with joy in a silver dress, throwing water at the camera. “By the end she’s real accepting of herself, just like, fuck it,” says Maguire, “I don’t have to worry about what I did, what I said.”

“Is there a way to make that shot fill the whole screen?” asks Dawn, talking to the back of my head. I turn around. “Oh,” she says. “I thought you were Liz.”

By Sue Cummings

LA Weekly, July 16 – July 22, 1993