By Greg Kot

Chicago Tribune, September 25, 1994

To others, her eagerness to sell, sell, sell, undercuts her songs. One of the few label executives who did not request anonymity when questioned about Phair was Bettina Richards, 29, who operates the Chicago-based Thrill Jockey Records.

“The only thing that’s aggravating is that there are other female songwriters I love that I couldn’t understand why they’re not getting the attention Liz Phair is,” Richards says. “Barbara Manning for one. To me, her lyrics are so sophisticated, but she’s also not aggressive about wanting to be successful. I don’t see her ever putting her chest on a record cover.”

Phair did just that on “Exile,” and the album drew a few leers because of several graphic sexual references in the lyrics, particularly in the song “Flower,” and an inner sleeve decorated with soft-porn photos of a woman resembling Phair. Phair also described the album to journalists as a response to the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” seemingly oblivious to the heresy she was committing by daring to mention her debut in the same breath as the holy grail of ’70s rock criticism. As profiles of Phair began to proliferate, her scattered explicit lyrics, Madonna-esque boy-toy photos and more outrageous pronouncements began to overshadow the album’s depth and richness.

“It’s embarrassing for me that those songs, those lyrics, would’ve been taken out of context,” she says. “They lose their humor and intelligence. I thought it was pretty savvy to do `Flower’ in a little girl voice. To me that was a statement in itself about what you can do about pornography, how to throw it back in the face of society. The point of some of those songs was to say things that shouldn’t come out of the voice that was saying it. The songs are total fiction. The feelings in them are true, but the stories are lies.”

Those who actually listened to the entire album, who enjoyed the irony for what it was, found a variety of perspectives about the toxic consequences of intimacy. They found a songwriter who could be confessional and vulnerable, but also tart and humorous, one who could break into an Ethel Merman voice to sing lines such as “I get away, almost everyday, with what the girls call murder.” And, whether the lyrical sophistication was appreciated or not, “Guyville” rocked-a punk-folk album that cut through the flannel-and-grunge decade like a shark fin.

It was audaciously accomplished music for an artist who virtually never played live before. This aroused suspicion and jealousy in the real-life “Guyville,” where playing low-paying Wednesday night gigs is the way to build credibility.

“My critics saw me as the lucky daughter that new daddies are going to take and make,” Phair says. “And (they ask) why do I deserve it? But it’s not about deserving it. It’s about the path of least resistance. I’m accessible enough in so many channels, and you can sell me really well. You don’t get big money based on merit … it’s not an issue in this equation.”

The path of least resistance can also mean cutting corners when it suits her; feelings have been hurt and gossip spread in retaliation. The term “Guyville” originated not with Phair but with a quick-witted Hyde Park musician, Chris Holmes, who was struck by Wicker Park’s “twisted cosmology of what it means to be a guy: tapping your foot to music that’s not there, checking out a girl while pretending to look at your beer bottle. … It’s almost something to be ashamed of.” The term was adopted by local band Urge Overkill in the title of one of their songs, and Phair-who is friendly with both Holmes and the members of Urge-found it a fitting umbrella for her album.

In interviews, Phair mentions both Urge Overkill and Holmes, but both go uncredited on the album. It’s notable only because the word “Guyville” has become part of the pop-culture zeitgeist; at least one Hollywood script is being floated using the word in its title.

A more serious careerist criticism is leveled by Henderson, who bashes Phair for “talking about how male-dominated the record business is in her interviews” and then hiring established figures such as Will Botwin to be her manager and Bob Lawton as her booking agent.

One female who Phair did solicit to help her was Katy Maguire, who directed Phair’s first video, “Never Said Nothing.” Her payment was exactly that: nothing. But Maguire says she doesn’t feel cheated.

“We did a video that would’ve cost at least $30,000 for $7,000, mainly because her record company wouldn’t allow her to do one any more expensive,” says Maguire, a two-time award winner at the Illinois Film Festival. “But she did me a favor too. The fact that I did that video is the first thing people notice on my resume.”

Maguire says she’d work with Phair again, if she got paid. “She does what she has to do to get ahead,” Maguire says, “and in a way I’m the same way.”

On her new “Whip-Smart” album, Phair does come out ahead, if only after a long struggle. She opens this song cycle about a woman’s self-discovery with a hushed piano nocturne, “Chopsticks.” It recounts a meeting at a party, a graphic promise of wild sex and then . . . nothing: “I dropped him off and drove him home, ’cause secretly I’m timid.”

By album’s end, however, Phair is giving the guy she once craved the bum’s rush. “Don’t be fooled by him,” she warns, and then turning to the object of her disaffection, she offers a blithe kiss-off: “You were miles above me/Girls in your arms/You could’ve planted a farm/All of them hayseeds.”

Whereas at the end of “Guyville” she’s still sorting out her emotions, at the climax of “Whip-Smart” she blows town, scattering her former lover’s empty promises like so many wild oats.

As the album progresses from lust to recognition to rage and finally to independence, the songs have women and men swapping roles in a fairy tale world filled with lions and tigers and bears. In this magical realm, almost anything is possible-men can even stand inside a woman’s shoes. On the album’s title track, a male Rapunzel is locked in an ivory tower, while his mother offers a prescription for escaping it.

“It’s saying to the guys, `This is how women get out of their traps. It’s applicable to you,’ ” Phair says. “The whole album is a woman’s statement, more so than `Guyville,’ which was more introspective, more about expressing feelings that had been suppressed. I’m asserting my right to be who I am, which is the best feminist there is.”

More convincingly, the album asserts Phair’s ability to write great pop songs. With “Super Nova,” “Cinco De Mayo,” “Whip-Smart,” “Jealousy” and “May Queen,” the album has a bounty of potential hits.

“I’ve always been obsessed with the idea of stuff that I listen to on the radio, and I wanted to be what I’d experienced,” she says. “I want to contribute to my generation’s sounds, what it associates with the times. `Girl rock arises.’ I want to be prominently in that. I want to be part of what girl rock was, circa 1994.”

That Phair is already speaking of her new album, indeed, her career in music, in the past tense is no slip. She talks about building a “nest egg” so that when she’s no longer “Little Miss Wonderful,” she’ll have a financial cushion to begin some other, more likely less-lucrative, artistic endeavor.

“I think I’ve got it pretty good, but I don’t like the frenzy of it, I don’t like the fear and the pace,” she says. “Rock demands that you hit and get out. Or you become one of those lifers; I’ve seen their faces and they’re just withered. . . . They have that total hardened look about them, that seen-it-all look. After the last year, I can already tune a lot of it out, I’ve become tougher-skinned, and I’m not sure that’s a desireable thing.

“This profession is a little more extreme than a lot of other professions. People don’t have a lot of sympathy for that because you get all the big freebies, but really all any of us are doing is packing away the money for when we’re out on our ass and starting up the next phase of our life. I’m gonna make sure that when I come out of this I don’t just land back where I was at 23.”

But wouldn’t she miss the attention? Phair spikes a pasta shell with her fork and shakes her head in dissent. “But here’s what I would miss: The fact that anyone wants anything I’ll do. It would be a bitch to say: `I’m a great director, look at this. Look at what I can do.’ Now it’s like, `Great, fantastic, thank you so much.’ When I don’t have the ultimate saleable thing anymore, when Liz Phair is no longer the voice of the now, and is just the voice of nostalgia, I’m gonna have to get back down there and hustle someone else like people have been hustling me. And that’s gonna blow.”

Like a “Guyville” guy, pop culture is fickle; “the voice of the now” is constantly being rediscovered, scrutinized and discarded for another even more daring and photogenic. Like a “Whip-Smart” gal, Phair has figured out how to play the game on her own terms-with cunning, a hint of ruthlessness and a wink. She enjoys the celebrity game for what it is: frosting, froth, banter, packaging, mirth.

But Phair the Celebrity has caused Phair the Artist to be perceived differently. In the months when “Exile in Guyville” was just a great album instead of a phenomenon, it was the songs that caused a stir. Now that the music has been reduced to a glib quote attached to a dimpled smile, it seems most opinions about Phair are based on anything but the songs.

Virtually any pop performer who has tinkered with irony and image over the years-most famously David Bowie, Prince and Madonna-has been branded a fake or worse, and had their artistry demeaned, their sincerity questioned. But Phair is among the first of these pop chameleons to spring to success from the ’90s underground, and as such the ideological crossfire is especially intense. On the one extreme is the indie-rock crowd that craves raw honesty from one of its own, and cringes when the music is undercut by the slightest hint of self-promotion. On the other is an industry that thinks of music in terms of packaging and economics, and has finally found an “indie-rock queen” to sell.

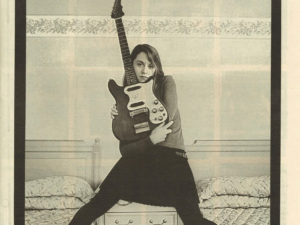

Phair’s strategy is to try and have it both ways, which tends to bug both sides. In her music and marketing, contradictions collide-“Shirley Temple joins a biker gang,” as she describes it. The songs on “Exile” and “Whip-Smart” rarely embrace one emotion, their “raw honesty” seldom can be distilled into bumper-sticker platitudes. Instead, the overall mood is one of ambivalence and irresolution, each song like one view from a merry-go-round, the perspective ever-changing. Just as the songs resist instant categorization, Phair’s primping and posing in photos and interviews can’t easily be dumped into the bin marked “cheesecake”: She can be coquettish, but she’s also the girl next door, the woman of substance, the tom-boy with a guitar.

In taking her too seriously, one misses the joke, the thrill of the ride. In taking her not seriously enough, one dismisses a songwriter who weaves plainspoken confession and poetic fantasy into insinuating melodies. Phair keeps threatening to outsmart herself on the way to selling a million records, but one senses she wouldn’t have it any other way.