LIZ PHAIR STANDS onstage with her eyes closed, the palm of her hand pressed against her forehead, rubbing in a slow circular motion. Last night in Madison, Wisconsin, Phair and her band played the first show of what she has insisted will be a brief tour to ride the seemingly endless wave of hype and genuine fandom earned by her debut, Exile in Guyville. Tonight she’s in Minneapolis for the first of two sold-out shows, and already she looks weary. The band, trying to get through the soundcheck, waits for her lead, but for the moment she’s frozen in position, hand to her head, definitely in another world. Trying to bring her back, guitarist Casey Rice plays the Keith Richards-style guitar chords from “6’1″,” the song that opens Guyville. He plays them again and again and again.

Touring has been something of a burden for Phair. When Guyville blew up last year, the 27-year-old singer/songwriter had barely played live at all, an almost heretical inversion of the standard indie-rock program of endless gigs leading up to a first album. Consequently, her performances have been dicey propositions; many, in fact, have been disasters of stage fright and sloppy playing.

This evening, however, Phair and her band — bassist Leroy Bach, drummer (and coproducer) Brad Wood, and Rice — acquit themselves reasonably well, working through most of Guyville, plus a handful of hard-edged hooky new second album, with passion and good humor. There are some wrong notes, some moments when Phair seems to lose the beat and Wood, the obvious backbone of the band, gracefully slips back in the groove to compensate. But the all-ages crowd adores her. A boy of maybe 17 tosses a pair of Jockey-style briefs on stage; another, pulling up his shirt to reveal a nipple, gestures at Phair with a Magic Marker to get her to sign his chest. Members of both genders scream, “I love you, Liz,” and, not surprisingly, these fans know all her lyrics. When Phair launches into a speed-trial a cappella version of “Flower”, the explicit and oft-quoted paean to female lust on Guyville, the crowd is right there with her. The experience of watching dozens of well-groomed, mostly suburban Midwestern adolescent girls singing, “I want to fuck you like a dog / I’ll take you home and make you like it,” is memorable, to say the least. Talkin’ ’bout a revolution, indeed.

AS FOR JUST what it is about Exile in Guyville that’s made such an impact (the record took first place in the Village Voice‘s 1993 Pazz & Jop Poll and has been a mainstay of college radio since its release more than a year ago), Phair still claims ignorance. “I don’t know,” she says, curled up on a ratty lounge chair in an upstairs room of the club. “Was it Reagan? Did he repress us for so long that this feels new?” She’s quick to rattle off names of artists who preceeded her — Chrissie Hynde of the Pretenders (“I got lost in their first record”), Patti Smith, and those on the early riot grrrl scene — and wonders why she’s been picked as women rockers’ great white hope.

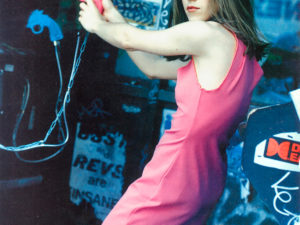

Phair, for all her tough-talking sexual swagger, projects a much lower-key image than any of the above-mentioned performers; she’s more a Sandra Dee than a Mae West or a Katherine Hepburn. An adopted child, she grew up in Winnetka, Illinois (a comfortable suburb of Chicago that until recently had the highest per-capita income in the nation), the daughter of a doctor and a teacher. She was a good student and, as she puts it, “a good girl.” While she went through a phase of trying to be a rocker — “no bra, ratted hair, lots of chains, Sonic Youth T-shirt” — now that she is one, she looks, well, rather preppy. Onstage in Minneapolis, she wears small, rather prim gold earrings, a neat long-sleeved black ribbed turtleneck, brown leggings (no holes), and designer boots. Her hair, fine brown with blonde highlights, looks just-washed, and if she’s wearing any makeup, it’s extremely subtle. She looks, in fact, like most of the suburban girls in the audience. This seemingly contradictory image — that of a conventionally feminine, but not extravagantly pretty five-foot-two girl taking the guys around her down a few notches while frankly broadcasting her passions and desires — is what makes her unusual in the rock world. In a word, she seems real.

That apparent realness has been her blessing and her curse. In interview after interview, she’s felt compelled to stress that her songs are not strictly autobiographical. “No one in this business seems to understand that celebritydom has to do with the blurring of your self and your image,” she says, exasperated. “I didn’t lose my virginity when I was 12, and I don’t want to fuck everyone until they’re blue. People expect me to be Liz Phair all the time, but I’m Elizabeth Clark Phair and I have an entirely independent existence.”

That existence currently involves a live-in relationship with a film editor with whom Phair appears very much in love (she even brought a sweater of his on the road that she “likes to sniff”). Her life with him and his 14-year-old son hardly fits the rock ‘n’ roll stereotype, aside from the pet rat (“When we all watch movies, we let him run around on the couch”), and is one of the reasons she dislikes touring so much. This stable scenario seems an important reality check for Phair, who, shortly after Guyville was recorded, experienced fame-induced vertigo. “It really fucked me up badly,” she says. “[I was] very miserable and very self-centered, totally wrapped up in my own world. The way I got sane again was by saying this is all my job, this is not who I am, [the album] is just something I made… and by meeting my boyfriend.”

A dyed-in the wool punk rocker with a pink-and-purple mohawk, her boyfriend’s son also has provided a sobering perspective. “He isn’t the least bit impressed with my rock ‘n’ roll credentials,” Phair says, laughing. “I come home, and I’ll be like, ‘I’m an indie queen’ and then we’ll all go out to buy some furniture or something, and he’s like, ‘You yuppies.'”

IF GUYVILLE CHARTED the dynamics of failed relationships, Phair’s new album sounds like it may try to chart those of successful ones. “Supernova”, except for its use of language, is a fairly straight-ahead pop-rock love song (“Your kisses are as wicked as an F-16 / You fuck like a volcano and you’re everything to me”), while “Whip-Smart”, with its chipper chorus borrowed from Malcolm McLaren’s “Double Dutch”, is a list of all things a particular mom plans to do in raising her son (“I’m gonna lock my son up in a tower / ‘Til he learns to let his hair down far enough to climb outside”).

Successful relationships, of course, don’t always mean common ones. “The whole album’s about role reversals,” Phair says, “about how our interactions put usinto roles, and how I define what a woman’s and a man’s role is. In Guyville, you know who the girl is and who the guy is. Next album that’ll be reversed; there’ll be men being exploited who I’m trying to save.” She cites an example as “Willie the Six Dick Pimp”. “It’s a really funny song. It’s about this guy, a man with male prostitutes, who is going around the country, who steals my boyfriend, and I’m chasing him down.”

This may not be the song that shoots Phair into Top 40 rotation. But if there’s anything that’s defined her as an artist so far, it’s been her desire to subvert people’s preconceptions about women — about their art, their desire, their complexity — and, in doing so, about men too. She’s played fast and loose with masks and images in her music and even in her marketing (she got a friend who resembles her to pose semi-nude for a photograph on Guyville‘s inner sleeve) in an effort to be, as she puts it, “the manipulator [as opposed to] the manipulated.” Yet now, as she herself admits, her image has taken on a life of its own. In a characteristically loaded metaphor, she compares Liz Phair to a hand puppet that she wears herself, but that “everybody gets to stick their hand up there and go at it for a while, [too].”

It’s a reality that all performers must come to terms with: that the meanings they intend their art to communicate get bent, lost, or even inverted in the course of things (the way Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.” became a nationalist rallying cry in spite of its politcally critical lyrics). So it’s not terribly surprising to see the drunken frat boys at Phair’s second Minneapolis gig (a 21-and-over show) shouting out things like, “Nice ass,” and “Fuck and run, bay-beee, fuck and run!”

Clearly uncomfortable, Phair pushes through the performance with almost no between-song banter. Unbelieavably, she launches into “Flower” near the end of the set; when she hits the line, “I want to be your blow-job queen,” a roar rises from the audience so wild, so drenched in alcohol and testosterone, that it evokes the scene from Last Exit to Brooklyn in which Trixie is dragged from the bar by a crowd of drunken men. But nothing like that happens here, and Phair follows up somewhat cheekily with “Girls! Girls! Girls!” (“I take full advantage / Of every man I meet”), during which the guys in the band file offstage, leaving Phair alone and strumming her guitar, mugging with a curious mix of confidence and hesitancy.

Before the show, Phair had looked down from the club’s balcony at a bunch of young women dancing together. “Oh god, look at them,” she had exclaimed. “That’s me, when I was like 18. [My girlfriends and I] would always go to the club early and dance with each other. It was before the guys got there; that was always the best time.”

These two wildly contrasting scenes — obnoxiously drunken boys and innocently dancing girls — from the war between the sexes make conflicts like those in Northern Ireland or the Middle East seem like schoolyard disputes.

GIVEN THE STRANGE demands of her current job, Phair seems to be holding up pretty well. But it seems unlikely, for all her obvious strength, intelligence, and savvy, that she’ll be spending her life criss-crossing the country in a tour bus. She and her art seem more private, more thoughtful than that (one reviewer described her work as that of a “mall rat singing acoustic confessions to bedroom walls”). While she has definite aspirations to reach a wider audience, she’s more interested in doing it through the buffer of recordings and film. Since completing work on her new album, Phair has been working on a long-form video, which will incorporate clips of some songs and which she will write, star in, and direct. (“I had them put it in my contract,” she points out.)

And though it might make her indie peers sneer, Phair has a highly pragmatic, decidedly unromantic view of her current profession and its demands. “I don’t think I’ll ever stop making music,” she says. “I’ve been writing songs since I was a little kid. But there’s such a difference between doing it in a professional way and doing it just for the music. There’s no way I’m going to say I’m not in it for the music [now]. This is like what I’m doing with my career for my 20s, a good little resume thing. I’m gonna try for three more albums, see what it does to me, how it will mutate me — because it will, that’s unavoidable — and then if I don’t like it I’ll fall back into something else.”

Her paradigm recalls the path chosen by another great rock ‘n’ roll artist, Patti Smith, who pulled out of her career at its frantic peak to raise children and make art at home. “That’s exactly what’s on my mind,” she says. “I’m looking forward to it; my maternal instincts are kicking in big time.”

She pauses to consider this and lets out a laugh. “Isn’t that funny? Before, [I had] rock ‘n’ roll as this carrot, like, ‘I’ll work this shit job and then I’ll be a rock star.’ Now I’m like, ‘I’ll do this rock ‘n’ roll shit for a while; then I’ll be a mom.'”

By Will Hermes

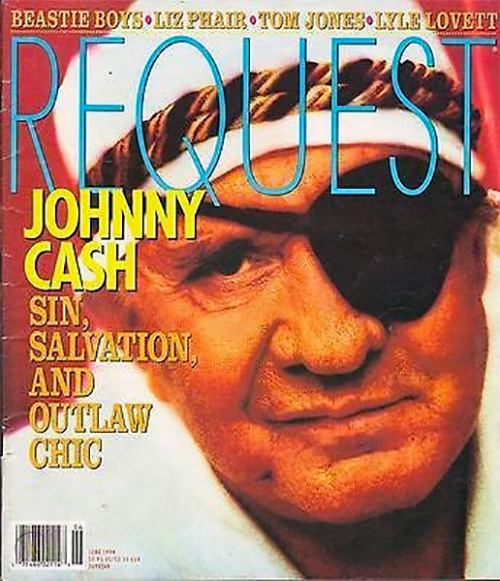

Request, June 1994