- Here are some pieces of Liz Phair. The best parts she wisely reserves for her work, her music, her art, her life — they are not to be found here, unless by accident.

Consider these fragments in any order. They are numbered for handy reference. The are a Polaroid, all indifferent focus and faded color. We are obliged to contemplate the cost of adulation.

Liz Phair and I will probably never meet again, so do not be fooled into believing I have seen anything more than who she was this Friday in Chicago, a person struggling with the choices abruptly, unexpectedly presented by her life and her art.

Here is the primer: The first release from Liz Phair, Exile in Guyville, sold a quarter-million copies, which is either a lot or not very much, depending on where you stand along the continuum of commerce. It was received as striking, in some circles, in part because Exile… spoke of sex without whispering.

The second release, titled Whip-Smart, comes after the maelstrom (male storm?) of unexpected success, sales, critic’s polls, magazine covers. The question will be: Which is better? It’s not an argument she can hope to win; she has been changed; fans are fickle, faddish.

Before, Liz Phair was, in order: the adopted daughter of an AIDS researcher and an art historian; a child of affluent suburbia; a student at Oberlin; an artist given to disturbing charcoal paintings. She is still shaped by the past, only altered. Now she is also an indie sex symbol. Ponder that contradiction. - We meet for breakfast. A woman with blonde hair, wearing jeans and a blue sweatshirt, chains her bicycle to a tree. She could be Liz Phair, who appears in blurred photographs on her album covers, and who paid a model to assume the suggestive poses inside Exile in Guyville. Instead, the bicycle rider proves to be a waitress. Liz Phair arrives a few minutes later, driving a blue car with two airbags and stuff on the floor.

This is part of Ms. Phair’s allure. She could be anybody’s sister or daughter.

Except.

Friend to girlfriend, on hearing that I was off to Chicago to interview Liz Phair: “Better fit him for a chastity belt.”

Such stupid cruelty.

It became mandatory to comment on the lyric “I want to be your blow job queen,” as if that were all she had to contribute to the dialogue. As if that very private thought, once give public voice, could only mean that the singer was… what, an uncontrollable nymphomaniac?

Trent Reznor, another piano player (she switched to guitar) from the middle-class Midwest, can write and sing “I want to fuck you like an animal/I want to feel you from the inside” with impunity.

“It created this whole bedroom environment,” Liz offers, “this fantasy world that no one knew a girl like me would have. Of course, they did in some sense, but not publicly. There was no archetype. It’s what your sister’s doing in her bedroom. And as my boyfriend likes to say, it was because the girl next door — Mary Ann from Gilligan’s Island — was suddenly pretty much showing off her pussy.” It was a revelation, in 1993, that women enjoy sex? Or a relief, maybe. - Liz says: “I no longer can tell you honestly — and I’m an extremely opinionated, relatively spoiled child — what’s good about me and mean it. I cannot tell you who I am. And it ought to be really simple. It ought to be back to the old, well, you’re a college-educated suburban what-not who has an interest in the outdoors and art.”

- So this woman named Liz Phair made a record called Exile in Guyville, a song-by-song response to the Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street. High concept. A challange, a puzzle, an exercise, a task completed except that she invested a great deal of her buoyant, exuberant self in those 18 songs. And what did she expect?

“I thought a bunch of guys in the neighborhood that I wanted to impress would take me seriously,” she says. “I thought that I would be… included, that I would be seen as more than a girl in the scene. Even when I went to Oberlin, most men talked about music among themselves and were relatively pedantic. You couldn’t really say anything that they wanted to hear. They were ensconced in their little subculture, and I pretty much just wanted to flip them off. I wanted to be both re-evaluated for my worth, and at the same time included, because I knew what they were talking about.”

High concept. A feminist response — or, alternatively, a female response — to the Rolling Stones. Rock critics who, as a caste, are predisposed to bestow far more importance upon lyrics than they deserve, who are basically nerds who at present have a well-intentioned understanding that women ought somehow to be included in the pop culture dialogue, well, they fell over themselves.

“And I wanted to impress a specific boy,” Liz adds. “It was my last-ditch wooing effort.” - Somebody else, too. Somebody more absent lurks at the edge of her songs. She jumps spaces between people with the skill of a military brat who has learned to make friends quickly. Except that Liz Phair is adopted. “About five percent of my ambition is the idea that if I get visible enough my parents will come to me. And I won’t have to go find them. I thought that was a really good idea.” Somebody’s daughter. She’s tried to resolve that question a couple times. “Connecticut doesn’t release files,” she says, quietly. “They might not want to be found, and if they did want to be found, what would that do to my sense of the possibilties in life? I’ve been given a free reign to create myself. I could be anything because, frankly, one doesn’t know what I’m destined for.” Her boyfriend has a 15-year-old son. “I hope I have children,” she says. “I really desperately, desperately want to have a genetic link. I want to see something like me. I want that.”

- Watch her video for “Super Nova”, the first single from Whip-Smart. Her video. She directed it.

Videos are, in the main, an execrable exercise in marketing. Commercials that shove images into your head for each sanctioned song, instead of permitting the listener the ecstacy and inalienable privilege of getting the songs all wrong. “Super Nova” is worth watching largely for what it suggests might be possible.

“Now I’m directing my own videos,” she announces, with a taunting laugh. “Ha ha! That’s such a joy and pleasure to behold for me, even though I’m not doing them very well yet. I’m doing them well enough that you know I’m probably going to get good at it. And contractually, they can’t stop me.” She laughs again.

Watch television, with the sound off. Follow the camera, which is generally operated and directed by men, as it studies, frames, gazes without apology at the female figure.

Seventy percent of the audience for rock music (and rock music magazines) is male.

One of Liz’s costumes for “Super Nova” is an evening dress, or perhaps it’s a slip. Whatever, the fabric is black and sleek, but the camera never slips below her neck, never, through all the cuts, loses sight of her face, dwells on her curves. “I planned it that way,” she says. “It’s keeping you in my dance. I’m holding and letting you go, holding you and letting you go. Instead of someone capturing the little fawn.”

There is a pause, then a slight smile. “Would you buy that? I made that up on the spot. But it’s kind of true.”

That look she gives in “Super Nova”, instead of using the word “fuck”, which won’t do for MTV, is pretty close to one of the people Liz Phair really might be, if one actually knew her. - “My main preoccupation was my parents, my family and family friends,” she insists. “As with everyone, I have a whole long history with a group of families, where I had a certain identity. And the most marked change in my life was trying to assimilate who they had thought they knew. And the irony of that was that they dealt with it relatively well. However shocking, it was also titillating.”

- Her laugh is addictive. Time to make another record. Beset by — just ask Tracy Chapman, Don McLean, Kurt Cobain — “a flock of subconscious seagulls,” Liz calls them. “All these different whiny voices to appease. No room left for me, what will I do, what do I want to hear from myself? So much about ‘Can you do this again?’ What was it? What am I supposed to be doing again? No, I can’t do that again. I’m sorry.”

She went to some of the places, re-enlisting producer (and ex-Shrimpboat stalwart) Brad Wood. But inescapably, her life had changed, complicated and what had once been easy and natural had been transformed. - “I had to go to the big picture to write this second album,” she says, “because no one’s giving me any time to be a part of life, to then write about life. I’m not part of it anymore. I’m stuck in that little fake universe of narcissism. It’s only recently that I finally got it. I was just Miz Career Girl, out there doing it, staying on top of it. Assuming that, as my whole life I’ve been fruitful creatively, without trying — good or bad, it was there, and it was enough to choose from — that there could be some good. It never occurred to me that I wouldn’t have enough material to put something good out.”

“I gave myself two allotments: Two songs on this album can be about how I feel about being Liz Phair. I didn’t put on any fake songs. I had to picture myself in a larger perspective than last year. I couldn’t write off the year I’d just gone through, but I had to pick, what does Liz Phair want to say? What does Elizabeth Clark Phair want to say? A couple of songs were really current that I’m really proud of, like ‘Jealousy’ or ‘Support System’ or ‘Alice Springs’. Actually, that’s not current, but I changed the words so it feels current.”

“And it’s going to be different anyway, because I’d fallen in love, and I did not feel mopey. I feel pretty much optimistic. I had to write an album out of context.”

That absent guy from Exile…? He’s still around, sort of. “The person I was writing to, I still use him,” Liz says. “But I have no desire to get together with him. I need him as a representative of an ideal which clearly he isn’t going to uphold, simply as the fantasy Prince Charming. Most girls would do a lot better if they would throw Prince Charming into the art mode and settle for Mr. Next Door, because they’d be happy and fulfilled by catering to both. He’s in the second album; he’s all over the second album. I turned him into a woman,” she laughs. “And if you knew him, that’s so great!” - “Lately I’ve been feeling bad about myself because I don’t think that men flirt with me anymore. I used to be a very flirtatious girl.”

“I used to be someone who would go into a room and get it all coming at me. And now I’ve completely got this little circle around me.” She draws a circle on the carpet, and there is little breathing room between that line and her. - “My family had never heard me play guitar, and I’d been in my room playing it. I would not play for anyone, not my boyfriends, not my friends, not anyone. I actively went out of my way to make sure I’d never have to.”

The mythology of indie rock involves a lot of male-bonding sweat in a cramped, stinky van, relieved by sleeping bags on strange floors, free beer and 45 minutes a night of music. Liz Phair just made a record. Then the machine, like an involuntary muscular response, cranked up. And never mind that she was and is plagued by crippling stage fright.

She toured anyway.

“I only toured because I was sick of being afraid of it, was sick of feeling like stage fright was my only excuse,” she says. (“You gotta have fear in your heart,” from “Shane”, echoes in my headphones.)

The critics were merciless. “I don’t care,” she says. “I’ve heard their barbs, but they’re usually not paying attention. They get everything wrong: they’re not really there. They come knowing what they expect, and if I disappoint them, they go beserk. The real trick is to remember who you have to answer to. I don’t have to answer to them. I never thought that I was going to be able to perform. I think it’s a mighty task that I stood up there with my poor little guitar. I don’t want to be a band. I didn’t want to be a band, ever.”

She is very close to tears. The vulnerability and openness which underlie her music becomes awkward between strangers.

“I’m going to have to play some this fall,” she says in the middle of another thought.

She may play some this fall, but she will not tour.

Or at least she’d better not.

“I had bloody, violent dreams for about two weeks,” she says, “which ceased on the very day I told my touring agent — I didn’t finalize it — but I’m thinking of canceling the whole tour. They were all very polite to me on the phone: God knows where that phone flew after I hung up.”

Here’s the point to the thing: “I have less ambition — these are some truths I have learned, these are hard facts — I have less fucking ambition and less passion for what I do by a good, measurable degree than I did before anyone gave a flying fuck who I was. I have been depressed and disillusioned by all my efforts to be on top of this, instead of underneath. But it’s a very big wave, a big machine, popular celebrity. And I do have a strong, strong sense that I was born to say some things. It’s in me.”

And here’s the cost: “Okay, the beast is a good word for it. We all use that, and I used it before I became a part of it, before I became a left claw. Nothing I can say to my parents or my friends, who want to know why I don’t go out, why I don’t call them, why I’m constantly feeling beleaguered will explain it. It makes me call them less because I can’t pretend. And I can’t explain to them why it’s different from their job, which is getting them down.”

Another pause. “I’m not going to tour. But I am going to use up all my video money. That’s inspiring. That’s exciting.” - Liz says: “I hate the perfect take. I hate the flawless performance because there’s nobody there. There’s no picture. I hate the flawless lyrical line. You don’t think that I could write something that I could sell to Whitney Houston? I could. It just would be so bland, so universal, everything that I would want to say, that would sound like a letter from me, would turn into those letters your mother made you write: ‘Thank you for the gift, I always wear it.'”

- Liz is working the camera. That is she is posing. She has driven us to a railroad bridge near a chocolate factory adorned with feuding gang graffiti. On a near wall, at the end, she guides us to a long, multi-part essay on the role of language, reading and rap music in black culture. The gang graffiti is cross-tagged with messages like “Kill!” or “Dead!” This piece runs perhaps a hundred feet, complete with the notation ©1992, and remains untouched. A few respectful comments have been added at the conclusion.

I walk toward the far end, to read the beginning. A black face with close-cropped hair pokes out from a shanty, a mattress, some canvas, a sheet of plywood. Our eyes meet, we nod, I turn back.

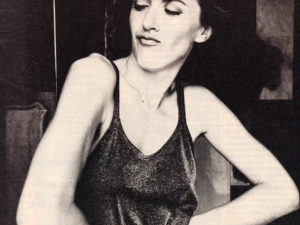

Liz is working the camera. Commuter trains pass slowly, mostly empty, a few faces wondering who the model might be so they can tell their wives over cheesburgers in suburban paradise.

Liz is working the camera, but she is no longer present. She assumes awkward, unbalanced positions, offers up not the certain grace of her conversation, but something else. A public persona she has worked out. Perhaps seeking to find a middle ground between the photographer’s expectations of a woman whose songs are so directly sexual, and her own experience of her self. - Liz says: “I’m at that wonderful, interesting point where if my career did start going down, I don’t think that would be such a bad thing for me. I don’t think it would be so bad to return to a life of smaller magnitude, smaller audience and a more interested audience, who wasn’t needing the next body to be thrown on the fire of sacrifice. I don’t think it’s such a healthy thing artistically. I was too unknown, and now I’m too known. So I’m kind of in a neat position where I don’t mind fucking with what I’m supposed to do because I don’t mind if it fails.”

“What I do mind is that I don’t believe in myself anymore, that I don’t believe in what I do. So I’m trying to go back to why I did this in the first place. I like to delve into my subconscious, and rock ‘n’ roll at this level doesn’t let you do that much.”

By Grant Alden

Raygun, November 1994