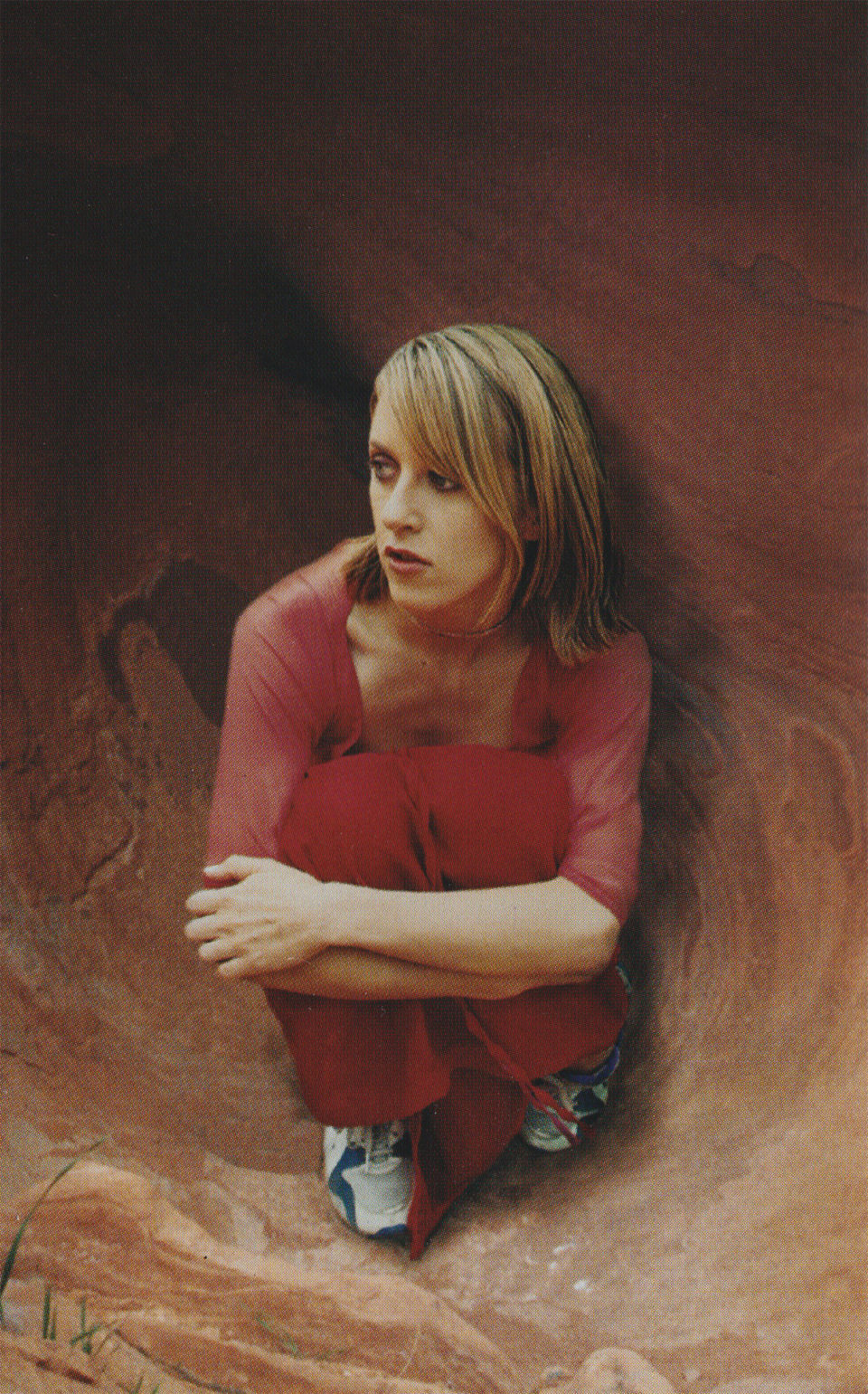

When she looks back on her short career, particularly her 1993 debut, Exile In Guyville, one of the benchmarks of ’90s rock, LP has just one regret: “I should have, you know, worked on my act.”

She says this sheepishly, as though confessing a terrible thing. Still, it’s hard to take her seriously: One of the charms of the critically lauded Exile, and the painfully rough live performances that followed its release, was that Phair didn’t have much of an act.

She never bothered to sell her arty, bracingly blunt, sexually forward songs. Hailed by women as a tough sister and men as a welcome change from singer-songwriter coquettishness, she approached the whole rock-star thing with a who-cares slouch. That was her gimmick: she concentrated on crafting little lo-fi gems, and didn’t appear to care whether her voice cracked or anyone even got what she was saying.

As she breaks a four-year silence with Egg (Matador, ***1/2), which arrives in stores Tuesday, the once-aloof Phair has changed her tune. Now she actually wants to be heard. And understood.

It took years of offstage transformation, she says, for her to realize she’s serious about music, and even longer to face the fact that she has a responsibility to the songs, her audience, herself. To that end, she has assembled a permanent band (with an excellent female background vocalist), and scheduled a full tour. And for the last four months, she has been taking twice-weekly voice lessons.

Sitting backstage at the Waterfront Entertainment Centre during the recent Lilith Fair, dressed in a tailored skirt and blouse, the 31-year-old rocker traced the steps along her winding path, and castigated herself for squandering the opportunities that came knocking way back when.

“I wish I’d have been more prepared for it,” she says of the adulation and scrutiny that came with Exile. “I don’t know why, but I never expected to perform. I didn’t adjust too well. If it happened today, I definitely would pay more attention to performing. Being out here [at Lilith] with these incredible women has made me look back and wonder: What was I doing? Why wasn’t I working on my craft?

“You watch Natalie Merchant. The way she plays the audience is amazing, very exotic. You get swept away. She pulls them along, always stretches what they’re expecting. She has such control–not just over the music, but the audience.”

As Phair grows more animated, it’s clear this isn’t some overnight epiphany. The woman who once sang about her prowess at oral sex has spent years on an “anguishing” quest to rediscover her musical identity. She had always drawn on personal experience for her narratives, and suddenly her circumstances were more mundane, less the stuff of wide-screen existential searching: In 1994, she married Jim Staskauskas, who worked on some of her music videos. They had a son, Nick, now 18 months old, and established a home life in Chicago, where Phair grew up. She tried to shoehorn recording into her life, but found herself stopping the project when things got hectic.

“I wasn’t sure I was going to continue,” Phair says of the period following her 1994 sophomore effort, the uneven Whip-Smart. “I didn’t feel like I had anything to say… I wasn’t confident of my abilities. Nick’s entrance into my life pulled me out of serious doldrums. Suddenly I felt like I wanted to write again.”

But that impulse didn’t initially translate into great art: When she turned in some songs to her label, the reaction shocked her. “They looked at it like, ‘Is that all that’s left of you?’ ” she recalls. The term housewife came up. Phair took up the challenge.

“I realized there was more of me, and that I’d been wrapped up in my child and friends and family. That’s when I finally felt ready to go back and gather myself up.”

Producer Scott Litt, of REM fame, was involved throughout Egg‘s gestation, which he describes as “a boxed set’s worth of work for just one album.” Though she was going through lots of life stuff, he says, Phair was very clear about the music she wanted.

“She had a bunch of songs that could have been Exile In Guyville, Part 2, but she wasn’t comfortable doing that. She wanted to make a real advance. She was searching a little bit, and to her credit she persisted… What she ended up with was something strong and personal that is clearly a step forward.”

“Polyester Bride”, one of the first songs Phair wrote after returning to work in earnest, captures a chunk of her dilemma. It’s a conversation between Phair and a bartender friend, a drink-pouring wise man who’s a sucker for her “lucky pretty eyes.” As she wonders what she should do with her life, he puts her situation in perspective: “Do you wanna find alligator cowboy boots that just went on sale, or do you wanna flap your wings and fly away from here?” he asks on the chorus.

“It was really important for me, that song,” says the native of Winnetka, Ill., an affluent Chicago suburb, whose mother is an art professor and father is chief of infectious diseases at Northwestern Memorial Hospital. “Because there’s a part of me that wants to cop out and be a shopper. It’s nice to be stupid and shop. I needed to face up to that choice between the suburban pattern or seeking out an individual life.”

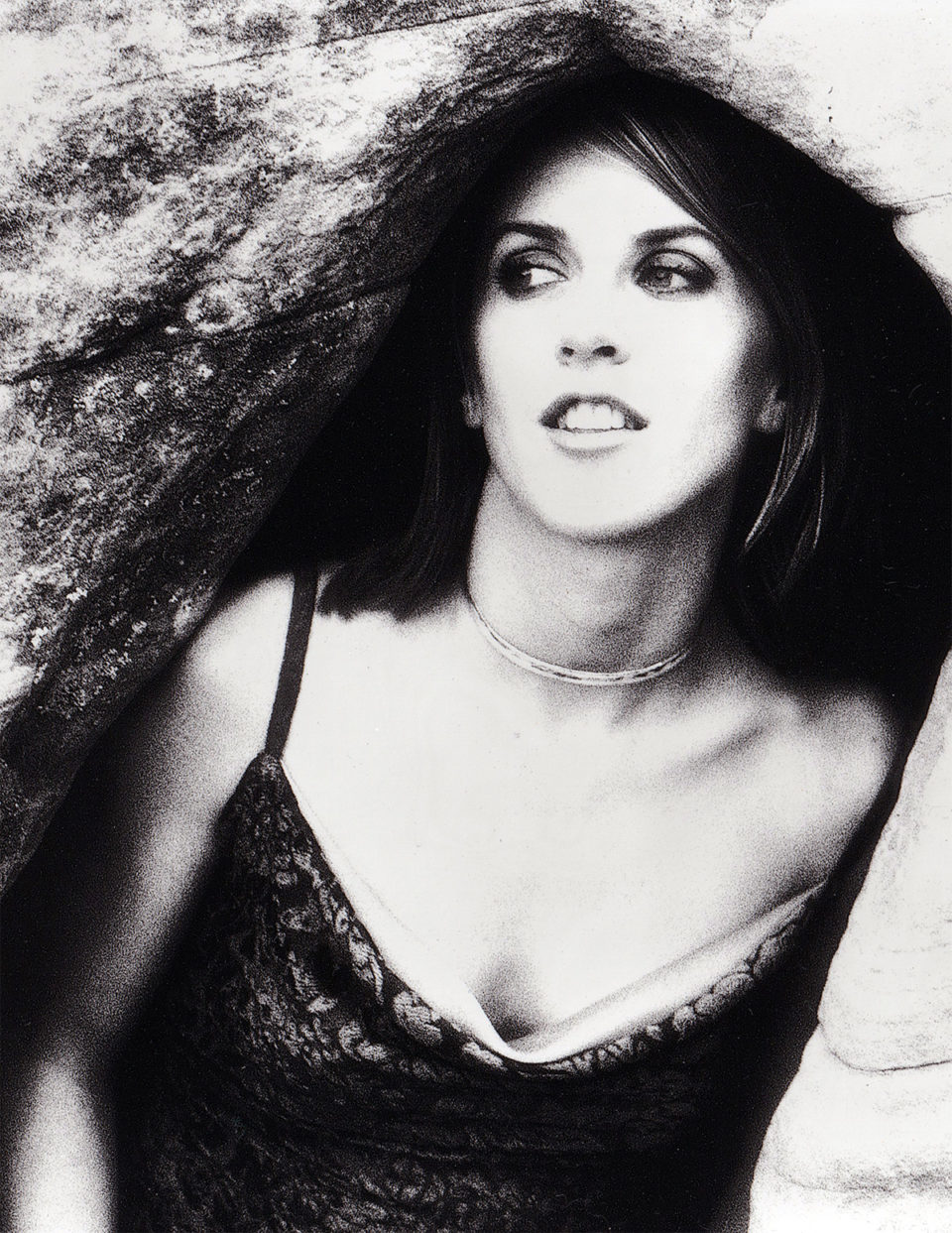

“My biggest strength is the honesty with which I write, and if that offends people, too bad.”

Liz Phair

From there, Phair says, the floodgates opened. She wrote small philosophical songs about love and commitment: One, “Love is Nothing”, turns on the line “Love is nothing like they say, you gotta pick up the little pieces every day,” while another, “Go on Ahead,” explores the conflict between being a parent and needing time for oneself.

She wrote songs about icy women for whom “just sitting next to a mortal makes their skin crawl,” and songs that express her desire to be “cool, tall, vulnerable and luscious.” She wrote songs that fold tense mother-daughter conversations into chiming cookie-cutter pop (“What Makes You Happy”) and songs that ditch verse-chorus structure in favor of rapid-fire spoken-word imagery (“Big Tall Man”). Several of the album’s standouts–including the title track, which she says was inspired by a dream–culminate in gorgeous multipart chorales that veer close to madrigals.

She returned to a song, “Johnny Feelgood,” that had been lurking in her journals for years. The account of a woman who has a sexual awakening at the hands of a domineering man, it’s a foursquare rock anthem with a subversive twist: The guy is no ordinary brute–he’s a sensitive type who’s got “petals on the bed of his sweatsock drawer”.

Phair’s stream-of-consciousness lyrics are unsettling: “I never realized I was so dirty and dry until he knocked me down, started dragging me around in the back of his convertible car… And I liked it.” But the song isn’t about abuse, she explains. It’s about the ways power is transferred in relationships.

She began writing the tune just after getting her degree in art at Oberlin College in the late ’80s, when she fell under the spell of a man who had strong notions about male and female roles.

“There I was, out of school and extremely aware of any injustice against women. He wasn’t like anyone I knew and it was exciting. It freed me up. I became more alive… I thought it was important to write about it because we’re so attuned to things like that signaling abuse, case closed. There are always subtleties, and I like to be the one who, in a caring way, says, ‘Wait, consider this.’ “

Phair believes this fascination with nuance has been misinterpreted. Some people hear her risque lyrics as nothing more that attention-getting ploys. She argues that that’s a shallow interpretation.

“I’m a really private person, but there’s a streak in me that’s totally into saying what everybody is thinking. Getting some of those unspokens out there. My biggest strength is the honesty with which I write, and if that bothers people, too bad.”

She says she didn’t give much thought to how her husband would interpret her new lyrics. “He knows that the songs have many different origins and sometimes may seem to be about me but are about somebody else. It’s not like he’s looking for clues.”

But, Phair knows, others are. After some prodding, she acknowledges that Exile In Guyville, which took top honors in the Village Voice‘s annual critics’ poll, helped pave the way for the work of Alanis Morisette and scores of generically angry female artists. She expects that Egg will be deconstructed to death, but is unconcerned that her more mature themes could be off-putting to those looking to settle the long-simmering gender war.

“To be honest, I never worry about how I’ll be perceived,” she says, sighing. “I’m just happy to be out and working. I spent a long time snuggled down in the writer’s realm, living a very inward existence. I feel like I’ve been sprung from something [and] given the chance to get out and try again.”

By Tom Moon, Inquirer Music Critic

Philadephia Inquirer, August 9, 1998