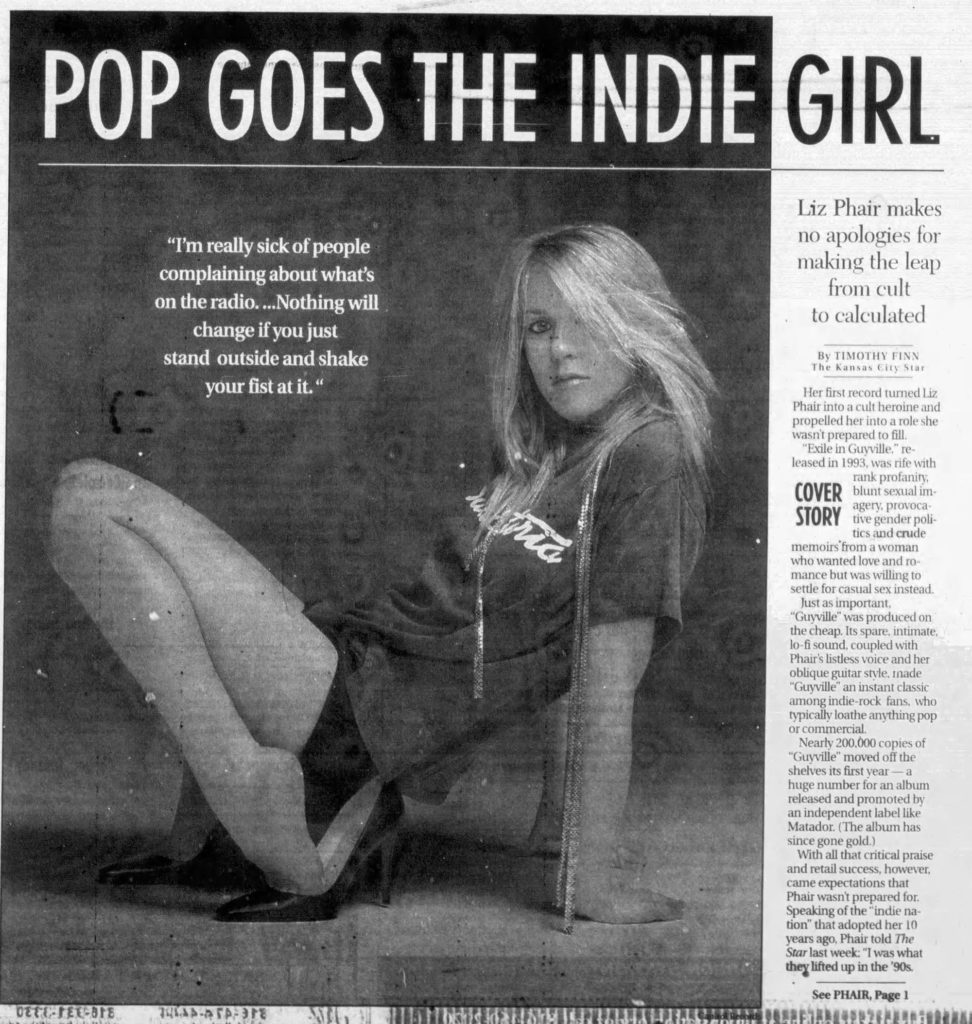

By Timothy Finn

The Kansas City Star, October 31, 2003

Her first record turned Liz Phair into a cult heroine and propelled her into a role she wasn’t prepared to fill.

“Exile in Guyville,” released in 1993, was rife with rank profanity, blunt sexual imagery, provocative gender politics and crude memoirs from a women who wanted love and romance but was willing to settle for casual sex instead.

Just as important, “Guyville” was produced on the cheap. Its spare, intimate, lo-fi sound, coupled with Phair’s listless voice and her oblique guitar style, made “Guyville” an instant classic among indie-rock fans, who typically loathe anything pop or commercial.

Nearly 200,000 copies of “Guyville” moved off the shelves its first year — a huge number for an album released and promoted by an independent label like Matador. (The album has since gone gold.)

With all that critical praise and retail success, however, came expectations that Phair wasn’t prepared for. Speaking of the “indie nation” that adopted her 10 years ago, Phair told The Star last week: “I was what they lifted up in the ’90s. They said, ‘Here’s our antidote to (the mainstream). Now we have our own Madonna.”

“I’m really sick of people complaining about what’s on the radio. …Nothing will change if you just stand outside and shake your fist at it.”

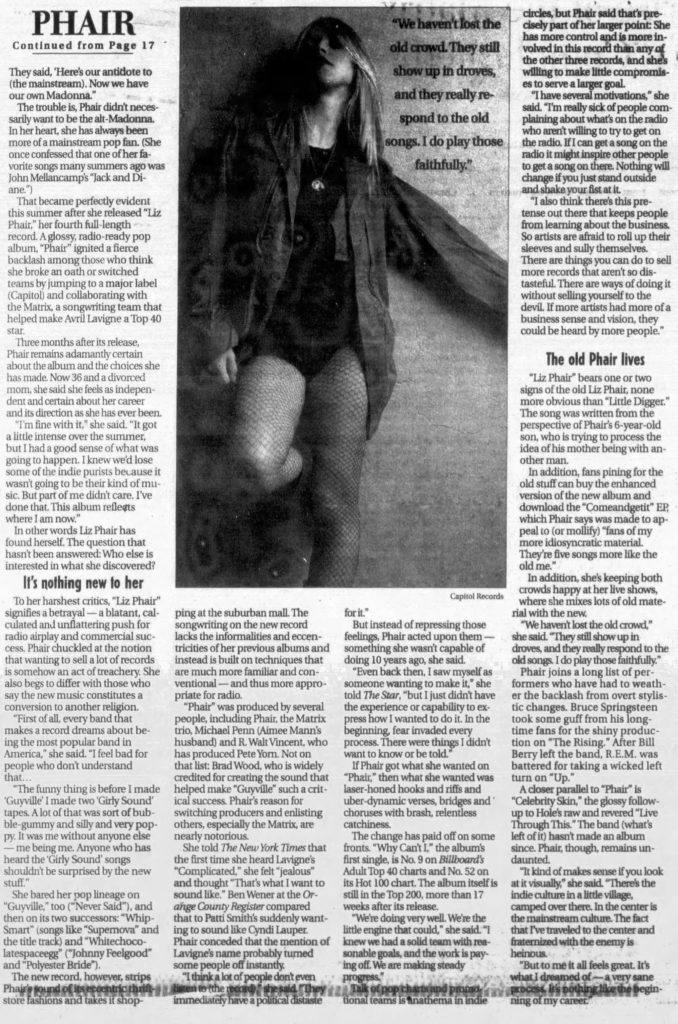

The trouble is, Phair didn’t necessarily want to be the alt-Madonna. In her heart, she has always been more of a mainstream pop fan. (She once confessed that one of her favorite songs many summers ago was John Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane.”)

That became perfectly evident this summer after she released “Liz Phair,” her fourth full-length record. A glossy, radio-ready pop album, “Phair” ignited a fierce backlash among those who think she broke an oath or switched teams by jumping to a major label (Capitol) and collaborating with the Matrix, a songwriting team that helped make Avril Lavigne a Top 40 star.

Three months after its release, Phair remains adamantly certain about the album and the choices she has made. Now 36 and a divorced mom, she said she feels as independent and certain about her career and its direction as she has ever been.

“I’m fine with it,” she said. “It got a little intense over the summer, but I had a good sense of what was going to happen. I knew we’d lose some of the indie purists because it wasn’t going to be their kind of music. But part of me didn’t care. I’ve done that. This album reflects where I am now.”

In other words Liz Phair has found herself. The question that hasn’t been answered: Who else is interested in what she discovered?

It’s nothing new to her

To her harshest critics, “Liz Phair” signifies betrayal — a blatant, calculated and unflattering push for radio airplay and commercial success. Phair chuckled at the notion that wanting to sell a lot of records is somehow an act of treachery. She also begs to differ with those who say the new music constitutes a conversion to another religion.

“First of all, every band that makes a record dreams about being the most popular band in America,” she said. “I feel bad for people who don’t understand that…”

“The funny thing is before I made ‘Guyville’ I made two ‘Girly Sound’ tapes. A lot of that was sort of bubble-gummy and silly and very poppy. It was me without anyone else — me being me. Anyone who has heard the ‘Girly Sound’ songs shouldn’t be surprised by the new stuff.”

She bared her pop lineage on “Guyville,” too (“Never Said”), and then on its two successors: “Whip-Smart” (songs like “Supernova” and the title track) and “Whitechocolatespaceegg” (“Johnny Feelgood” and “Polyester Bride”).

The new record, however, strips Phair’s sound of its eccentric thrift-store fashions and takes it shopping at the suburban mall. The songwriting on the new record lacks the informalities and eccentricities of her previous albums and instead is built on techniques that are much more familiar and conventional — and thus more appropriate for radio.

“Phair” was produced by several people, including Phair, the Matrix trio, Michael Penn (Aimee Mann’s husband) and R. Walt Vincent, who has produced Pete Yorn. Not on that list: Brad Wood, who is widely credited for creating the sound that helped make “Guyville” such a critical success. Phair’s reason for switching producers and enlisting other, especially the Matrix, are nearly notorious.

She told The New York Times that the first time she heard Lavigne’s “Complicated,” she felt “jealous” and thought “That’s what I want to sound like.” Ben Wener at the Orange County Register compared that to Patti Smith suddenly wanting to sound like Cyndi Lauper. Phair conceded that the mention of Lavigne’s name probably turned some people off instantly.

“I think a lot of people don’t even listen to (the record)” she said. “They immediately have a political distaste for it.”

But instead of repressing those feelings, Phair acted upon them — something she wan’t capable of doing 10 years ago, she said.

“Even back then, I saw myself as someone wanting to make it,” she told The Star, “but I just didn’t have the experience or capability to express how I wanted to do it. In the beginning, fear invaded every process. There were things I didn’t want to know or be told.”

If Phair got what she wanted on “Phair,” then what she wanted was laser-honed hooks and riffs and uber-dynamic verses, bridges and choruses with brash, relentless catchiness.

The change has paid off on some fronts. “Why Can’t I,” the album’s first single, is No. 9 on Billboard’s Adult Top 40 charts and No. 52 on its Hot 100 chart. The album itself is still in the Top 200, more than 17 weeks after its release.

“We’re doing very well. We’re the little engine that could,” she said. “I knew we had a solid team with reasonable goals, and the work is paying off. We are making steady progress.”

Talk of pop charts and promotional teams is anathema in indie circles, but Phair said that’s precisely part of her larger point: She has more control and is more involved in this record than any of the other three records, and she’s willing to make little compromises to serve a larger goal.

“We haven’t lost the old crowd. They still show up in droves, and they really respond to the old song. I do play those faithfully.”

“I have several motivations,” she said. “I’m really sick of people complaining about what’s on the radio who aren’t willing to try to get on the radio. If I can get a song on the radio it might inspire other people to get a song on there. Nothing will change if you just stand outside and shake your fist at it.”

“I also think there’s this pretense out there that keeps people from learning about the business. So artists are afraid to roll up their sleeves and sully themselves. There are things you can do to sell more records that aren’t so distasteful. There are ways of doing it without selling yourself to the devil. If more artists had more of a business sense and vision, they could be heard by more people.”

The old Phair lives

“Liz Phair” bears one or two signs of the old Liz Phair, none more obvious than “Little Digger.” The song was written from the perspective of Phair’s 6-year-old son, who is trying to process the idea of his mother being with another man.

In addition, fans pining for the old stuff can buy the enhanced version of the new album and download the “Comeandgetit” EP, which Phair says was made to appeal to (or mollify) “fans of my more idiosyncratic material. They’re five songs more like the old me.”

In addition, she’s keeping both crowds happy at her live shows, where she mixes lots of old material with the new.

“We haven’t lost the old crowd,” she said. “They still show up in droves, and they really respond to the old songs. I do play those faithfully.”

Phair joins a long list of performers who have had to weather the backlash from overt stylistic changes. Bruce Springsteen took some guff from his longtime fans for the shiny production on “The Rising.” After Bill Berry left the band, R.E.M. was battered for taking a wicked left turn on “Up.”

A closer parallel to “Phair” is “Celebrity Skin,” the glossy follow-up to Hole’s raw and revered “Live Through This.” The band (what’s left of it) hasn’t made an album since. Phair, though, remains undaunted.

“It kind of makes sense if you look at it visually,” she said. “There’s the indie culture in a little village, camped over there. In the center is the mainstream culture. The fact that I’ve traveled to the center and fraternized with the enemy is heinous.”

“But to me it all feels great. It’s what I dream of — a very sane process. It’s nothing like the beginning of my career.”

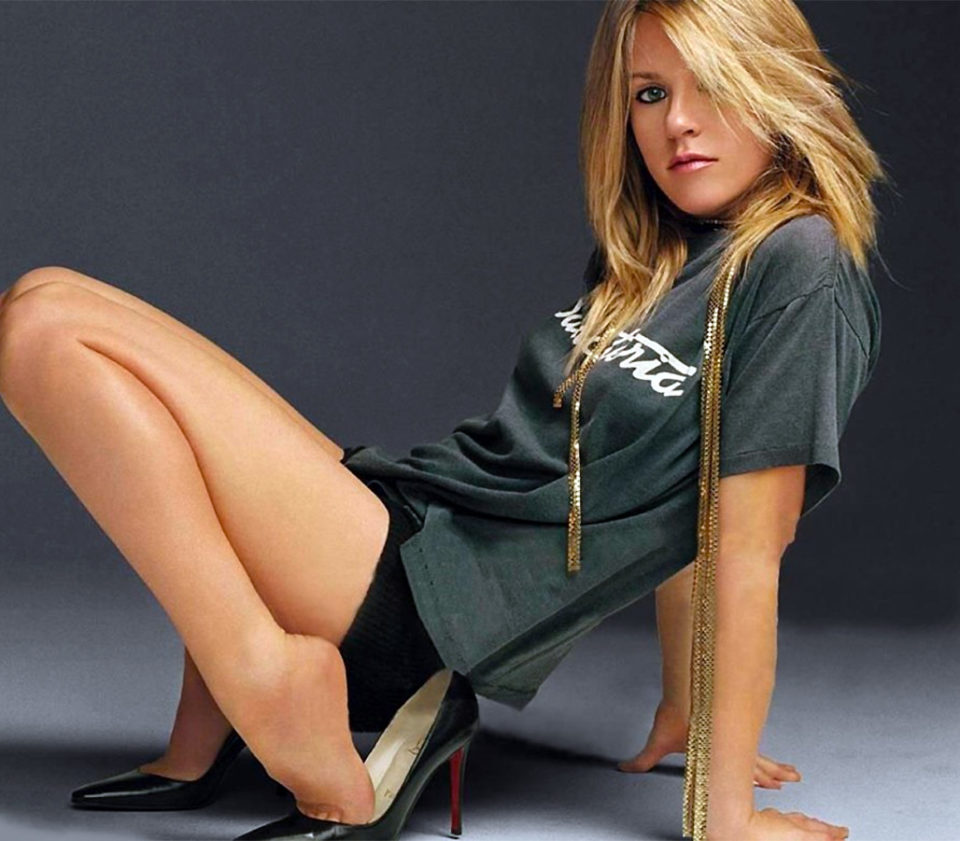

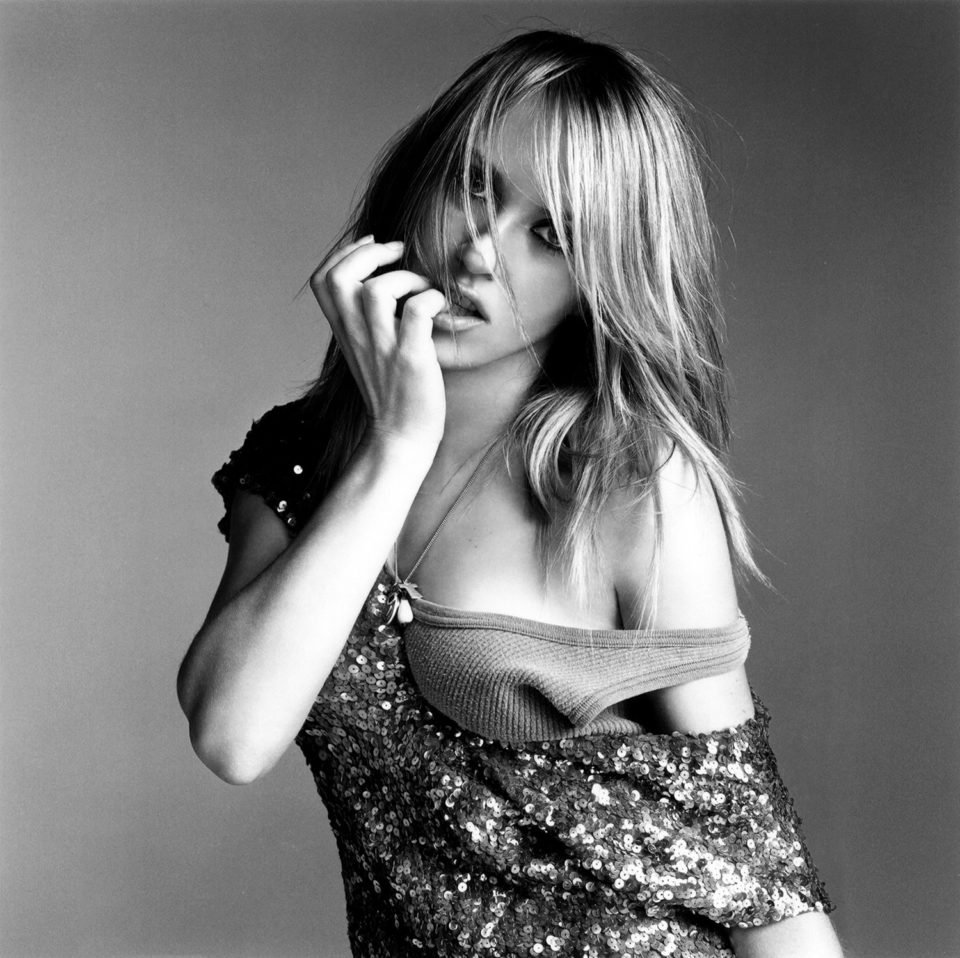

Featured Image: Liz Phair (Photo by Phil Poynter)