By Shelly Ridenour

Nylon, June/July 2003

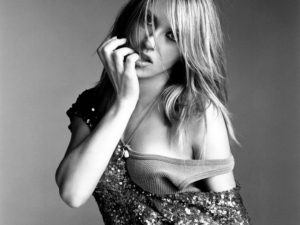

The break-up record may be a classic in the pop-rock canon — Matthew Sweet’s Girlfriend; Spiritualized’s Ladies and Gentlemen, We Are Floating in Space; hell, even Justified — but never expect Liz Phair to play by the rules. Though the singer’s marriage to film editor Jim Staskausas ended last year, Liz Phair is not mournful, angry, or even searching. Instead, her latest effort is about rediscovering how exciting crushes and first sex are. “Isn’t this the best part of breaking up / Finding someone else you can’t get enough of,” she sings on the sweet and sunny “Why Can’t I”. No longer railing against being burned by men, she’s singing the praises of younger guys — and she sounds more confident and in control of her life than the itchy, talk-the-talk girl of her 1993 debut, Exile in Guyville.

“I feel in control! I’m still frustrated by some of my own bad qualities in dating,” says Phair, adding that she’s a casual dater these days. “But I’m recognizing now that they’re my bad qualities, and not anybody doing anything to me. That’s my hurdle to overcome.”

Phair’s had a few hurdles to overcome in her career, too. A decade ago, she was regarded as the voice of a new sexual liberation. By her third record, 1998’s whitechocolatespaceegg, she had left her hometown of Chicago for Los Angeles, married, had a baby, and been on the cover of Rolling Stone. The Village Voice, which had crowned her album best of ’93, took potshots like, “riot grrl has been reduced to Liz Phair and her Calvins on a Manhattan billboard.” (When was Phair ever part of the riot grrl movement?) And reviewer after reviewer equated her domesticity with selling out. It was another knot added to the political, feminist-or-poseur tangle that surrounded Phair’s music and image. And Phair admits she felt a bit of pressure to show the world she wasn’t just a settled-down mommy.

“I still labor under that a little bit, too. I want to prove that I can rock, and I don’t know what it means that I feel I should prove it. Part of it is just that I don’t want to lose the fun and power that I feel when I’m out in Hollywood without my son. My response has been to divide my life. My life in Manhattan Beach… I don’t go out down here, it’s just all about my son, Nick. And when I’m out on the town, I’m out on the town,” she says. “I think the reason people don’t appreciate domesticity goes back to images of why people don’t respect women. It’s a lot of fucking menial labor. It’s laundry, it’s dishes. There’s nothing glamorous about that aspect of housekeeping. There’s no room for the feelings of women in their daily lives in rock ‘n’ roll. I think that’s unfair and wrong.”

While her fourth album is a celebratory affair, she is aware of critics have plenty of ammunition to attack Liz Phair. If you ever locked into the singer’s charm — and, certainly, she seems one of those love-’em-or-hate-’em artists — songs like the exuberant “Red Light Fever” and the bittersweet single-mom ballad “Little Digger” should give you pinprick thrills. But make no mistake: The sound is so big, the production so squeaky clean (“overproduced to within an inch of its life,” tsked the Austin Chronicle) that the whole thing might as well have a halo hanging over it. Crookedly, of course — after all, there’s a song called “HWC”, aka “Hot White Cum”. But for those of us a little exhaused by the “scruffy = better” or “lo-fi = more meaningful” thing, it’s summer refreshment.

“I don’t feel I’ve been untrue to my sentiments,” Phair says. “It’s just a bigger production.” Sure to be a big bone of contention is the fact that much of the record is produced by the Matrix, the three-person team behind Avril Lavigne’s Plexiglass sound (Pete Yorn and Michael Penn also worked on songs). “The Matrix are great, and they’re smart, and they’re talented. A lot of what people don’t like about Avril is Avril — the falseness of how she was marketed. These people just make songs, and they like big sound. But they didn’t tell the management to take a girl who is 17 and [have her] pretend to write the songs, even though it’s [really from] the perspective of a woman, [the Matrix’s] Lauren Christy, who’s 35, and who basically wrote them,” Phair says.

Meow. For her part, Phair is totally comfortable having traded in It-Girl status for thirtysomething self-assuredness. “It took me until the age I am to feel like my life was a reflection of what I’m doing in it,” she says. “It wasn’t other forces keeping me down or making me unhappy. I just like myself right now.”