And finally that year, with this confluence of bands, the Chicago rock scene drew national attention. White, the editor of Billboard, wrote a rave column on “Exile in Guyville” a few months before it came out. The magazine followed up with a slate of stories on its front page, all headlined CHICAGO: THE NEW CUTTING EDGE CAPITAL or some such. Record-company weasels were camped in town, and bands were getting signed right and left. Chicago was Uncle Tupelo’s second home; after the band split up, Tweedy settled here and started his plans for Wilco. Industrial rockers Ministry became the unlikely co-headliners of the second Lollapalooza tour. R. Kelly was in the process of going multiplatinum too. (I watched him film the “Bump N’ Grind” video at the Vic, across the street from my house in Lakeview.) Veruca Salt and Loud Lucy were picked up by Geffen. Jon Langford and Sally Timms from the Mekons came to town. Bloodshot Records became an important alt-country label, and Wax Trax was selling boatloads of industrial albums by groups with names like the Revolting Cocks. (A Wax Trax-related story is one “Hitsville” column that has always stayed with me.)

And this was just part of the city’s cultural scene. Milly’s Orchid Show was in full-swing; it was so good that folks like (then unknown) David Sedaris were the third- or fourth-best thing on the bill. Even a benighted non-sports fan like me could appreciate the sight of Michael Jordan standing rampant, like Zeus. Steppenwolf and the Goodman were famous, of course, but a woman named Mary Zimmerman was just getting started at a (literally) underground theater troupe called Lookingglass. (Zimmerman’s “Arabian Nights” remains the greatest work of art I’ve seen in any medium.) You could go see a play at Oobleck, bomb over to Wicker Park to see something at Czar Bar, and then go back to the North Side to see a late show at Metro or Lounge Ax; too many nights like this you could find me in the early hours of the morning at Peters near Lincoln eating French toast with Sheila Boo Sachs, the Reader’s art director. If the Replacements, say, were pretty great at the Aragon, ‘XRT’s Johnny Mars and Marty Lennartz and I might jump into a car and run up to see them in Milwaukee the next night.

A few years ago I was flipping through an old-fashioned paper datebook before throwing it out; I noticed one weekend, which included the following among a bunch of local shows: the Flaming Lips, at their psychedelic height, was on Thursday; on Friday Courtney Love utterly destroyed at Metro, ending the show by jumping into the audience, having her clothes ripped off, getting back to the stage, turning to face the audience nude, and flipping them off; Saturday night was Sinatra at the World; Sunday night the Lips guested on Sound Opinions.

And on Monday Prince played at Metro.

I’m sure there’s a lot of stuff I’m forgetting. In any case, in late December I started doing my top-ten list. (Back then, the Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop critic’s poll was a big deal—to us critics at least—so you worked on the list with an eye toward sending it off there as well.) I was going to do a little essay for the Reader, to accompany the list.

“What a year,” I thought, and started writing. I knew exactly what I was going to say.

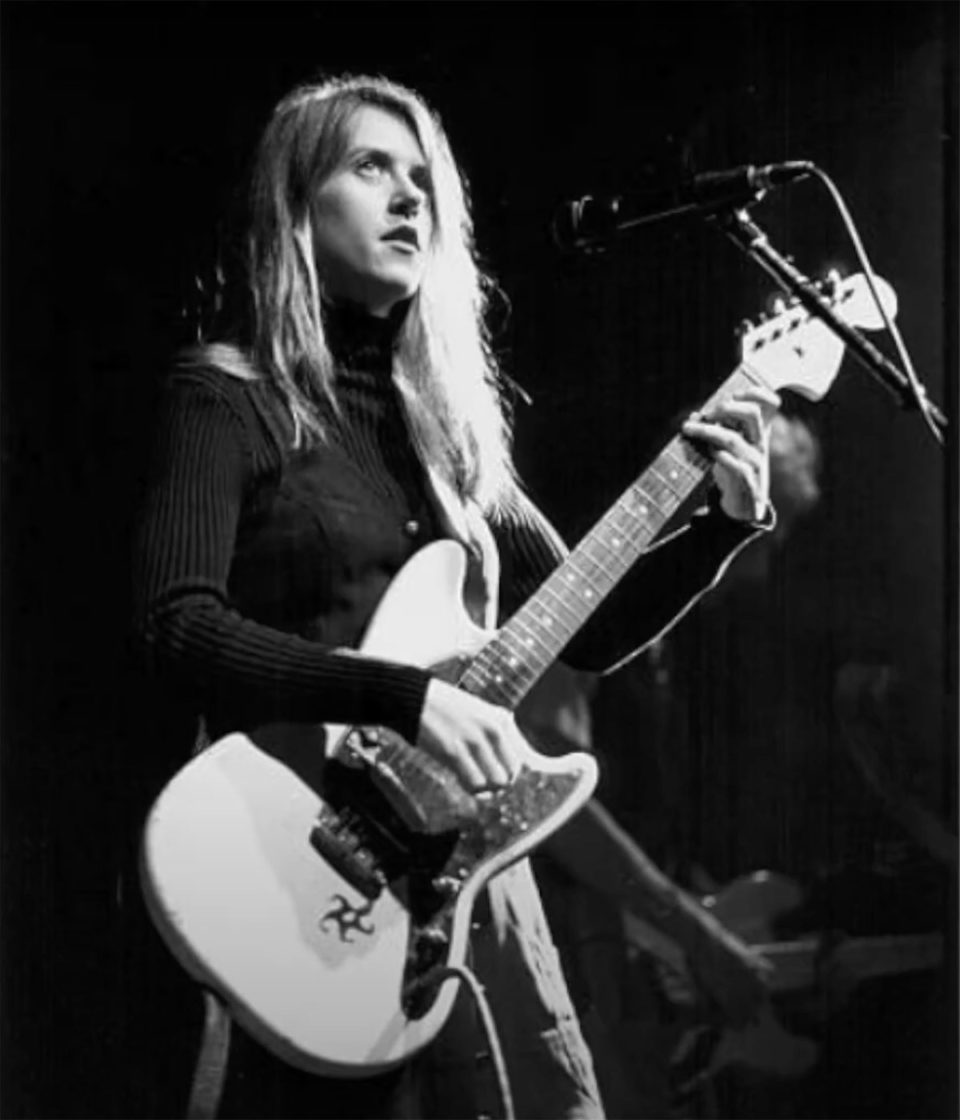

The Pumpkins didn’t speak to me, but even in a year of amazing records, from Dre’s “The Chronic” to Nirvana’s “In Utero,” I had to be honest, even if it seemed like I was boosting hometown bands: “Guyville” and “Saturation” were the records I’d listened to, and enjoyed, the most. They were patently the two loamiest, more enjoyable, most rockin’ records of the year.

Beyond that, I’d noticed something else. I’d been watching how artists become successful. You can be a hack, surely, but all three of these, while they certainly wanted to be successful, weren’t doing it by way of imitation, or by something philosophically or aesthetically awkward or forced. To the contrary, they’d all just led with their unique vision; in each case, it was driven by an inchoate sense, something along the lines of, “I’m going to do this and”—here came a statement of ineffable optimism—”people are going to hear it and like it.”

It is a personal aesthetic vision of belief, not supplication; a shout of confidence, not fear.

Back then, in the wake of “Nevermind,” “alternative music” was all the rage, and it was often used by labels to promote utterly conventional bar bands. I tried to be careful with my language and to explain to readers what the terms I was using meant. (This is the time, remember, when a lot of critics were into casually tossing off vague terms like “electronica” or—my favorite—”postrock.”) In the piece, I was careful to define the terms as I saw them.

Underground music was deliberately non-pop. Alternative? “Relatively personal music that doesn’t necessarily exclude pop.” I thought that was something that could include both Soundgarden and, say, Morrissey, Dinosaur Jr. or the Breeders. Philip Montoro thought this was “tortured,” but that’s okay. Art is complicated sometimes.

Being a rock star or a wannabe rock star looks great from afar, but in real life it’s hard. I exist on the far marginal edges of what you’d call the creative world, and let me tell you, when it’s just you and a blank, glowing, implacable computer screen, it gets lonely. How musical artists do it—creating words, melodies, verses, choruses, having first the nerve to play it for bandmates, playing it over and over just to get it to the point where it doesn’t totally suck—is beyond me. For the visionary ones, it gets worse, as they push things to the brink of absurdity, just to come to some feeble approximation of what they heard in their head, when what they’re hearing had never been heard before. How do you convey that?

Then you get to engage in the highly enjoyable process of managing your band. Here is one of Johnny Rotten’s most profound observations: “[You] must eat shit in the rehearsal room. The histrionics of the lead guitar, the excesses of the drummer, and the stupidity of the bass player have to meet on equal footing.”

And on top of all that there was this keening bank of criticism from the cheap seats, about selling out, being “careerist” (another frequent Albini slur) and the like. But here’s the thing: All those cool indie bands from the 1980s? They’d all gone to major labels: Sonic Youth, Hüsker Dü, the Replacements, Camper Van Beethoven, the Pixies and more, like R.E.M. before them, were all signed to major labels. Nirvana of course was as well. Cobain didn’t like hearing from fans that they couldn’t get his records.

Albini is known for an article that, in withering detail, explained how major-label contracts could end up screwing bands over. The implication of his attacks on me was that I was setting the bands up to be put into the major-label woodchipper.

My readers at the time were aware of this, but since time has passed and the audience has changed let me say that, if there was a pop writer in America in the 1990s who wrote more about major-label sleaziness in general, rising album- and concert-ticket prices, and ancillary consumer issues like scalping than me, I wasn’t aware of him or her. (Joe Kvidera, the manager of Tower on Clark, would let me know whenever some price increases hit.) I wrote so much about crowd safety that Eddie Vedder called to yell at me. These didn’t get mentioned in Albini’s broadside.

Some bands got screwed over by labels, true; they’d signed bad deals and Albini’s article was exactly the sort of corrective the young and naïve needed to be aware of. That said, being on a major could work out if you had some leverage (say, if they were in the midst of an alternative-rock signing spree and competing with each other for bands) and a good lawyer; and if you were careful, and didn’t run up too much in expenses against your advance. You could learn how to make records in a professional studio; you could make connections in the industry that over time could help you go off into a productive and even remunerative career if that rock ‘n’ roll stardom thing didn’t work out. (This is a whole other story, but it’s also true that there is a lot of dubious behavior by indie labels as well.)

Albini’s relationship to the underground always struck me as a bit paternal. He was like a scoutmaster with his wide-eyed charges, out on their first overnight campout. Sitting around the fire, he’d deliver a time-tested ghost story. “And then, out in the middle of the woods, I turned around and saw that… [hushed voice] I was being followed by a major label! They had Billy Corgan… and he was down on the ground and Bill Wyman was helping them. They were forcing him to… sell out! ”

Another thing: “Exile” and “Saturation” (and “Siamese Dream,” for that matter), are spectacularly and adventuresomely produced, each in its own way—highly emotional and evocative for Phair, overseen by Brad Wood; adamantine brilliance by the Butcher Brothers, for Urge; and sometimes dense soundscapes by Butch Vig, for the Pumpkins. (The hit “Disarm”—as different from the reigning Mötley Crüe and Guns N’ Roses stuff as you could imagine—sounded great on the radio in a new and different way.) Each in its own way demonstrated production extremes at the time that were understandably deliberately not given credence by a didact like Albini.

At the time, when the country still had powerful stations like the Loop freezing out the new sounds, these were not considered highly radio- or commercial-friendly. If these three artists didn’t have their own sound in their heads, they would have all behaved much differently and recorded much different albums. Urge wasn’t pretending to be grunge; Phair wasn’t pretending to be Madonna; Corgan wasn’t pretending to be the Cure. What I said in the essay was incontrovertible: Here were three artists who had some semblance of artistic integrity, who were trying to make their way in a complex world and displayed the neuroses to prove it.

In any case, that’s the story behind the column. Let’s see what Albini had to say.

The cleverest thing in his letter is a mischievous bit of rhetorical legerdemain. Albini has it that I was an indiscriminate promoter of all three: the Pumpkins, Phair and Urge. But of course I had had nothing to say about the Pumpkins from a critical standpoint and mentioned them only when, say, “Siamese Dream” went platinum. They were by far the most commercially successful band of the three; a casual reader would have thought I’d been salivating about the band all year.

Actually, in the essay I went out of my way to point out that Billy Corgan didn’t get much critical love in Chicago:

Corgan, whose teen-friendly guitar-rock seems a likely foundation for a Depeche Mode- or Cure-sized career, had the best ’93, finding the critical respect denied him in his hometown from the likes of the L.A. Times’s Robert Hilburn and the New York Times’s Jon Pareles (who named Siamese Dream their number-two and number-three albums of the year, respectively).

(My memory could be wrong, but I’m pretty sure neither DeRo at the Sun-Times nor Greg Kot at the Trib had the Pumpkins on their year-end lists.)

Then he went after the bands:

They are by, of and for the mainstream. Liz Phair is Rickie Lee Jones (more talked about than heard, a persona completely unrooted in substance, and a fucking chore to listen to), Smashing Pumpkins are REO Speedwagon (stylistically appropriate for the current college party scene, but ultimately insignificant) and Urge Overkill are Oingo Boingo (Weiners in suits playing frat party rock, trying to tap a goofy trend that doesn’t even exist).

Rickie Lee Jones was a star from 1979. She was a friend of Tom Waits, who’d been a respected recording artist for nearly a decade; her debut record was produced and overseen by Russ Titelman and Lenny Waronker, two of the most powerful producers in the record business at the time. (Waronker was president of Warner Bros. Records.) Her sound, though flecked with jazz, fit in well with the singer-songwriter work of the decade, and indeed was a bit retro, since by that time New Wave and disco were flourishing. Her record became an immediate sensation and she had a long and respected career.

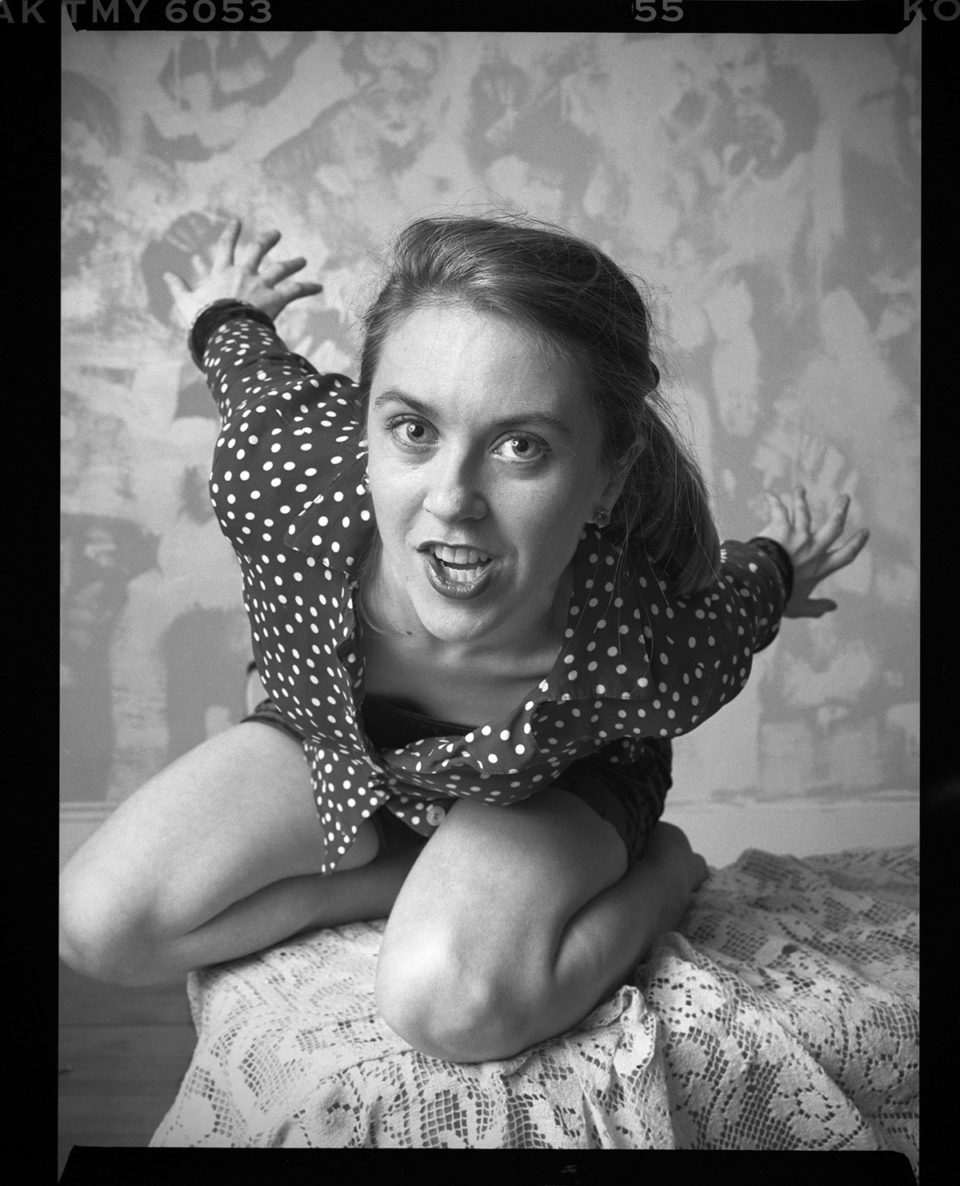

Phair, by contrast, had crafted a lo-fi girldungsroman that, pace Steve, had no commercial precursor I was aware of. Her big industry friend was a guy in a band called Come (I’m not making this up), which no one had ever heard of. She had a one-album deal with a label that, while très hep in indie circles, didn’t move as many records in a year as Warner Brothers did to the cutout bins in a given month, and was produced by a guy best known as a drummer for another band no one had ever heard of.

Besides being women, I can’t think of a way in which Phair and Jones are alike. Other than that, though, it was a very trenchant observation.

As for Urge, I hate to undermine such a great line, but for the record Oingo Boingo was a dreadful faux ska outfit with a dedicated following in L.A. and a few other places; how Urge, who were slowly evolving out of an unhappy sludge-like sound, had staked their career on a confusing double-reverse ironic palette of image-making, and generally came across as malevolent, is related to this I don’t know.

I know a secret about Steve Albini.

He’s a nice guy. He was very friendly to me when I came to Chicago (this is long before “Hitsville”) and I remember a terrific conversation about music over flan at that Mexican restaurant a few doors up from (then) Cabaret Metro. We drifted apart; he probably thought I was an idiot, and I had nothing to say about the records he worked on. A friend who’d known him at Northwestern—he’d been a journalism major—recalled a drawing Albini had done: A human head with a buzzsaw or something going through it, accompanied by the caption, “How it feels sometimes.” The ferocious and admirable guitar sounds of his Big Black albums aside, a reductive “Oh the horrors of life” shtick comes through most of his work: The title song of “Budd” was about the Pennsylvania politician who blew his head off on live TV; there was also the cover of the “Headache” album, which had a gruesome photo of an autopsy-room shot of someone who’d lost half his head in a car accident or something. (Note recurrent theme.) His second group was called Rapeman. (Kurt Cobain’s first band was called Fecal Matter but, in an early example of his being a commercial sellout, he changed it to Nirvana.) Albini is a good writer, though, and to this day remains reflexively unobsequious. (There’s a great scene in Dave Grohl’s “Sonic Highways” episode on Chicago where Albini is showing him around his Electrical Audio complex. “There’s another studio next door you guys don’t get to see, because fuck you guys.”) All that said, I know from personal experience he’s open and friendly to strangers.

Over time I got into a sort of range war with him, too. He’d rag on me on Chugchanga, the early Internet listserv he contributed to, and occasionally I’d do something to piss him off, like publicize or review the “secret show” in which he debuted a new band, dubbed Shellac, or needle him in passing on “Sound Opinions.” (“What Steve Albini doesn’t understand is that he’s a much better writer than he is a producer.”)

Albini the producer gets talked about a lot, but few take the time to examine the actual quality of it all. His studio work can be appropriate and even ageless, like that first Pixies album. But I think in other contexts his work gets old fast, and most of the high-profile clients from his salad days didn’t come back. The second PJ Harvey album, which was called “Rid of Me” and was produced—I’m sorry, “recorded”—by Albini, is the worst of her formative period; it’s unsubtle and almost cartoony. The producer Flood elicited better songs from her, and worked to create a more realistic setting for them on the followup, “To Bring You My Love,” one of the most sensational albums of the era.

Albini’s work with Nirvana is erratic, too. Too many of the songs on “In Utero,” the follow-up to “Nevermind,” are unvaried—and inferior—noise.

If you will recall, there was a contretemps at the time; Nirvana didn’t like the sound of certain tracks. Albini ran around saying Geffen had forced the band to lighten the sound on the album, and the band eventually took out an ad in Billboard defending itself. This was a first-class dickish move on Albini’s part, and a perfect example of the attacks from the left that came out of Albini’s overly romanticized underground from time to time. I came to Chicago from Berkeley, so I knew a bit about internecine leftist warfare, and it can be pretty sad.

Here, I think, is a revealing take on Steve Albini’s work, from the “In Utero” sessions, in a Chicago magazine profile from 1994:

Kurt would say, ‘I want to do a guitar overdub,’ and Steve would explain to him for a half-hour why it wasn’t a good idea, using all these weird technical terms. And Kurt would say, ‘Well, that may be so, but I still want to do a guitar overdub.’ And Steve would explain to him again why he shouldn’t do it. The last line of any of these lectures is always, ‘But you’re paying me, so I’ll do what you want. I have to put in my two cents because you’re paying me.’ But his two cents turns out to be, you know, five hundred dollars.

And that’s from one of his friends, second engineer on the recording and Shellac bandmate Bob Weston.

The band insisted on remixing a few of the songs, which all ended up sounding great. On the other hand, Albini’s original recording of the song “Dumb” remains, and that’s a song—and a production—that sounded great then and does so today.

I’d like to get to the heart of Albini’s note, which goes like this:

We harbor a notion of music as a thing of value, and methodology as an equal, if not supreme component of an artist’s aesthetic. You don’t “get” it because you’re supported by an industry that gains nothing when artists exist happily outside it, or when people buy records they like rather than the ones they’re told to.

My primary issue with this passage is the quotation marks around the word “get.” In poker terms, this is a tell.

But let’s move beyond that.

Two points: The idea that methodology is “an equal, if not supreme component” of what artists do is portentously wrongheaded, sophomorically reductive and slightly deranged, as I’m sure Cobain thought it was when Albini tried to lecture him about guitar solos.

I don’t care if Maroon 5 worked in orphanages, and I don’t care if Radiohead clubbed baby seals during the making of “OK Computer.” Rock ‘n’ roll doesn’t like walls, limits or humorless fundamentalists. The whole idea of rock ‘n’ roll is to break those sorts of bonds. The notion that operating in the clotted political bubble that is Steve Albini’s studio by itself is an aesthetic criterion at all, much less a supreme one, is difficult for me to engage with.

This lumpen romanticism has been paraded ever since by Albini’s amen corner, and I always wonder if those who quote it have ever taken the time to consider its implications, particularly when it comes to criticism.

I respect the approach, sure—I’d listen to a record recorded under that philosophy and give it the same attention I would an album not recorded by a fanatic. But I wouldn’t give it a few extra methodological happy faces in a review without saying so.

Because I’m a shill for major labels? No; because readers don’t want writers to be giving boneheads brownie points for posturing.

In the recent Reader piece, Philip Montoro’s version of this line of thinking went like this: “To my ears, Wyman fails to grasp that some musicians exist outside the industry by choice. He sees the division between ‘alternative’ and ‘underground’ as primarily aesthetic and social, and doesn’t acknowledge the economic and structural reasons for the latter to exist.”

Montoro is using a lot of words that don’t have much relevance here. You can be a sociologist and chronicle the behaviors of an underground group. Or you can be a feature writer and write a nice article letting other folks know about it. But both of those roles are different from those of a critic. It reminds me of how, a few years ago, everyone was talking about Paul McCartney’s new CD being sold in Starbucks. If you’re talking about extramusical stuff like that, it’s a good bet the record sucks.

Since I wrote about people who lived outside their various industries by choice, and since I myself worked on the margins of my own industry by choice, it was a phenomenon of which I had a tangential appreciation. What Montoro fails to grasp is that a reluctance to give an artist pats on the head for something isn’t the same as a lack of apprehension that that something exists.