Montoro doesn’t see that his far-fetched appreciation of this nonexistent dichotomy is at odds with Albini’s own peculiar wrongheadedness. Montoro’s saying I view the division between alternative and underground as primarily aesthetic, when I don’t see that at all, didn’t work under that assumption and never said I did. Being “deliberately nonpop” is a species of political decision. (And for the record, the “economic and structural reasons” the underground exists aren’t that much different from myriad other deliberately insular artistic enclaves, albeit with more slumming by guys from Northwestern.) I was simply asserting, based on reporting and my own observations that went way beyond the anecdotal, that some of the people who existed in that underground were harshing on people who weren’t in it, which is impolite and stupid. Albini, by contrast, was arguing that the aesthetics are inherent in the underground, which is adorable but isn’t true.

Since Albini’s attempts at argumentation are sometimes let down by his alternately acerbic and soapboxy verbiage, let me draw out what I think he and Montoro were really getting at, which has to do with commerciality.

They were saying that these three “pandering sluts” were deliberately creating music that was commercially minded—that they were trying to sell records—and that I was the stooge beating the drums to help major labels unload them.

Commerciality was a difficult philosophical issue for the bands at the time. A few years ago, in Salon, I wrote a long piece on the alternative years. I don’t want to repeat myself so let me just quote part of it here:

Which brings us to the poignant conundrum at the heart of the indie-rock way of life: How could they demonstrate this outsiderness, this authenticity, in a commercial environment? It was never quite articulated in quite so crude a fashion, but it was a given in that world at the time that there was a special group of true fans of any given band, surrounded by a much larger group of people who weren’t quite so worthy.

Indie rock was in effect a series of concentric circles, with each successively larger circle representing an inevitable dilution of the select. Whichever one you stood in, you scowled at the bigger ones. Were you a true indie rock fan, really? At the time, you could hear scenesters disparage Matador, the coolest and contrariest label of the era, as being hopelessly compromised.

What most bands did was draw imaginary lines in their minds: We’ll put handbills up, but not posters. We’ll do interviews, but never say anything serious. We’ll show up for the concert, but go on late to make clear we’re not eager beavers. We’ll do some college-radio interviews—and act bored to be there—but not mainstream ones, and if we do do mainstream radio, we’ll act even more bored! And we’ll talk to major-label people, if they insist, but get drunk and act like the fuck-ups we are when we meet, the better to have tales with which to regale our fans from the stage that night. And sometimes, to reward our really cool fans, we’ll have secret shows, so the uncool people can’t get in.

All this line-drawing affected real artists. Cobain wondered another thing as well. When pressed about it, he wasn’t exactly sure why it wasn’t cool to be played on the radio in the first place. Didn’t all the bands he liked growing up get played on the radio? When bands like Nirvana played live, they weren’t trying to endorse a lifestyle of social asceticism. They were presiding over a public event of joy and validation.

Why was that bad? Why was it worse if it got bigger?

You can say they were greedy, call them sellouts, think they were misguided. But the thing that drove Kurt Cobain, and the other indie bands, was a dream about pop. Money entered into the equation, of course, and why not? But something else was going on as well. As the 1980s went on, you could feel an interest building in something. It wasn’t interest in a new type of music, exactly. But there was an odd sense of a thirst for something… different. If you were one of these musicians, you could smell that need, and suddenly visualize yourself in a different world, one where kids everywhere jammed to your music, their hearts feeling that they would burst.

The most honest of these musicians admitted that they felt that way as a kid, and that it was a feeling that had driven them to the point they were at. The artists who went to the major labels could feel something hungry, almost animalistic, out in the wilderness, something alive that wanted their music.

You could look at things that way—or look at them Albini’s way. Let’s look at the next sentence again: “You don’t ‘get’ it because you’re supported by an industry that gains nothing when artists exist happily outside it, or when people buy records they like rather than the ones they’re told to.”

What he’s getting at is echoed by Montoro in the Reader from February 2: “Like many music writers, Wyman clearly considered the size of his potential audience when deciding which artists to cover.”

That was me: supported by the industry… sucking on the corporate teat… shilling for the major labels… and covering only popular artists. As I explained earlier, I didn’t “cover” things in the first place. I was blandly interested in what the majors put out in exactly the same way I was blandly interested in what Touch and Go put out. The majors had put out Ramones, the Clash, X, Prince, Talking Heads… Who wouldn’t be interested in them? Did I have to ignore things I wanted to write about just because they were released on a major label?

In Albini’s worldview, I was telling people to buy certain records because the industry told me to.

I wasn’t, but let’s say I was. What was I supposed to do then—stop telling people to buy those records and start telling them to buy his records?

I thought about this once back then and followed two trains of thought. The first was that, as I understood it, the idea was that I was supposed to take the fact that a band wasn’t trying to be popular and tell people to buy it based on what in Albini’s view was this “supreme” aesthetic consideration.

But if all critics did that, those bands then might become popular.

In theory you could end up with a remarkable commercial movement of artists—led by Steve Albini, their talents trumpeted by an enthusiastic and complaisant media—that disliked the mass audience and whose preference would have been to be disliked in turn by it… being paradoxically forced to accept its money and acclaim.

A fine kettle of fish that would have been!

The second train of thought was that, in the past, the utopian visions heralded by certain folks enforcing the idea of a supreme methodological aesthetic turned out to be not so good in the long run for artists on both sides of that particular cultural debate.

Besides all the reporting-based stuff I did on music-industry scumbagginess, I did something else, too, that bears upon some of the things Albini was writing about. There’s a dirty little secret in rock journalism, and that is that negative reviews barely exist. (Take a look at the music ratings on Metacritic sometime; they are almost always all green.) When Jon Pareles dismissed Coldplay in the Times a few years back, the reverberations went on for months.

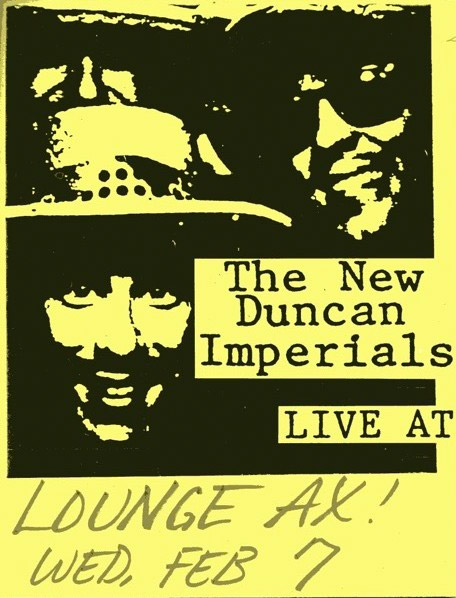

With the caveat, again, that I’m explaining something now that I think my readers at the time already knew, let me note that, in the Reader alone, I wrote highly negative reviews of Pearl Jam, Neil Young, Lou Reed, the Rolling Stones, Springsteen, Elvis Costello, Guns N’ Roses, Ice Cube, Dylan, the Eagles, Stone Temple Pilots, Lenny Kravitz, Eazy-E, the band Chicago, Pink Floyd, Michelle Shocked, Madonna, Pavement and 2 Live Crew, with the (pre-DeRogatis) rock critic at the Sun-Times and Strunk & White thrown in for good measure, some of these more than once and often at a length of three-, four- and five-thousand words—and those are merely the highly negative ones that come to mind immediately. Beyond that, there was not a quote-unquote powerful music figure in town, starting at Jam Productions and the guy who ran Soldier Field to radio-station program directors and running to club owners and bookers, including Metro and Lounge Ax, who did not at one time or another, and in some cases more regularly, call to express their supreme displeasure at something I’d written. (No email back then!)

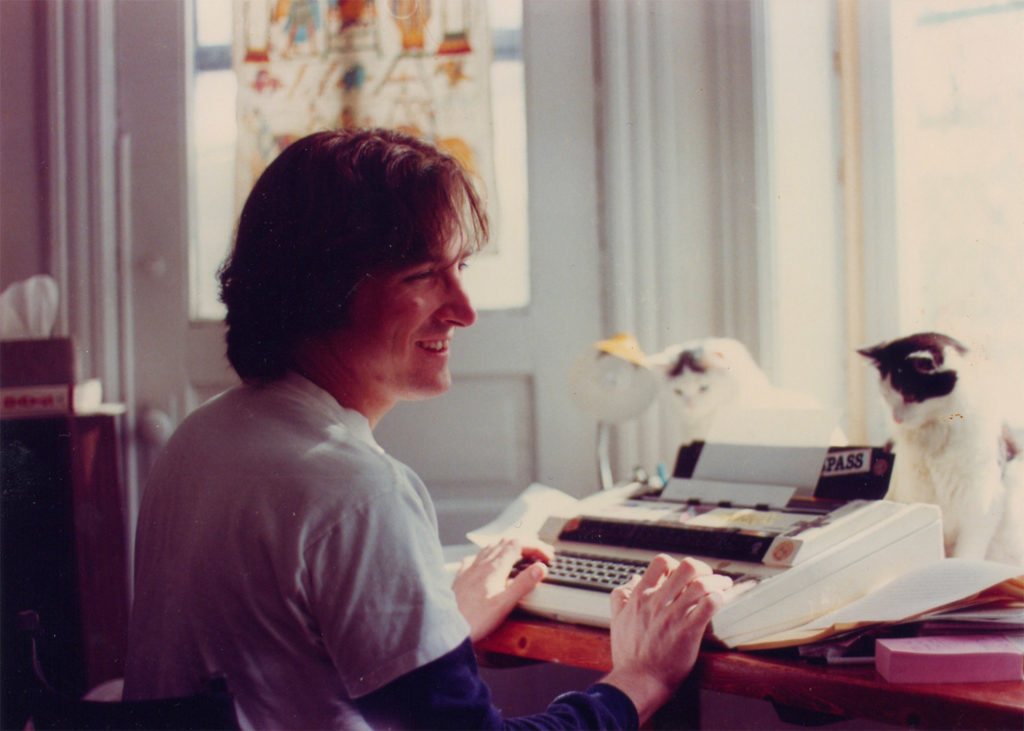

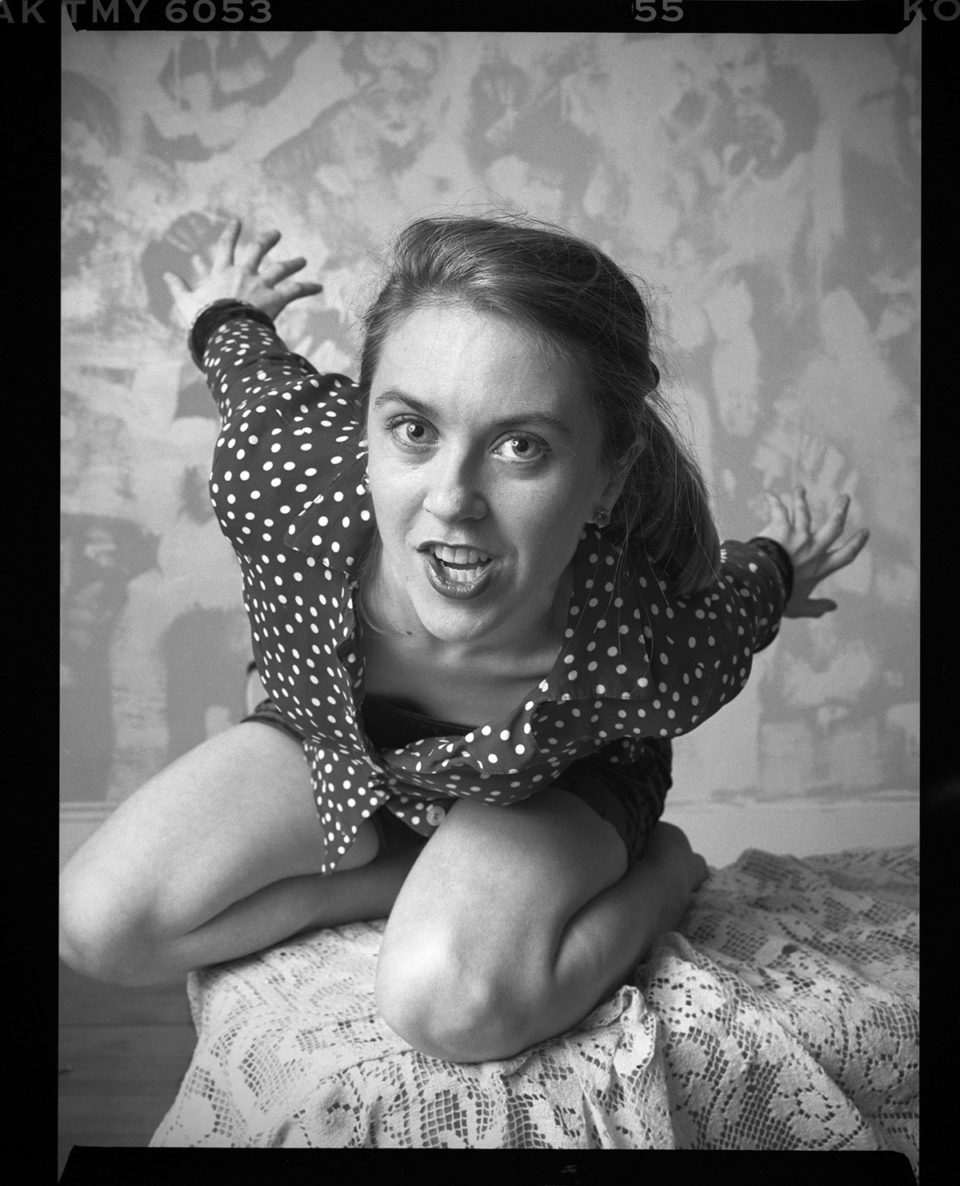

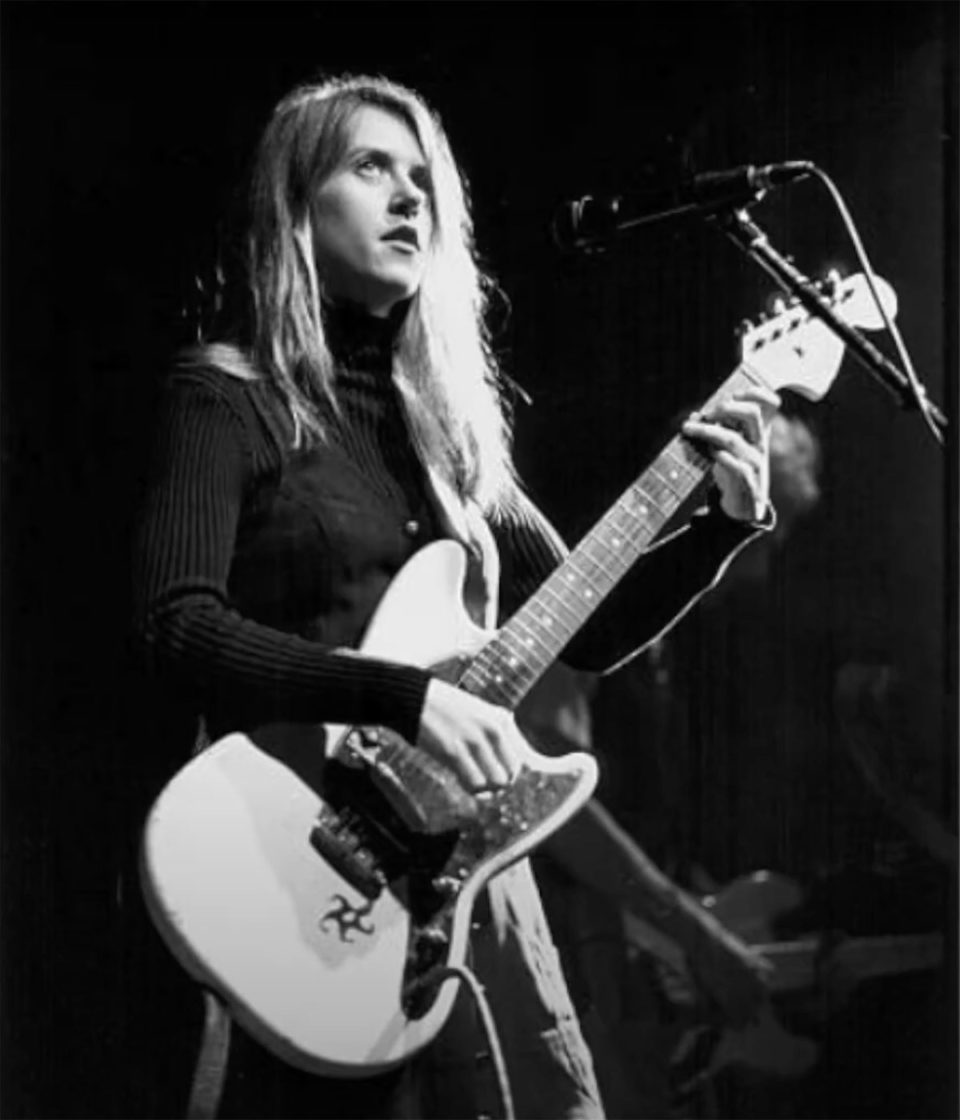

Before Phair, the local artist I’d written the most about was Paul Caporino, who had a band called M.O.T.O., put out his songs on cassette, and was so low-fi he recorded his drums through a pair of headphones. I wrote two back-to-back columns on a singer-songwriter named Jo Carol Pierce, who was in her fifties and working the overnight shift at a suicide hotline and didn’t sell a tenth as many records as the few the Jesus Lizard did. When I first wrote about Urge they were nobodies, and when I wrote about Liz Phair she was just a weird woman in a bar.

The dismal fact is, all of these things I’ve been describing combined together to ensure that the support Albini said I was getting from the industry was thin gruel indeed.

I felt okay not responding to Steve’s missive then, and still don’t feel I have to now, but if someone asked I would say, in the end—aside from the fact that it was exactly the sort of thing that catalyzed the subject of my essay in the first place, that it was directed at a straw man, that it was entirely wrong on the facts, that it was done mostly for the benefit of his campfire kids and that, finally, it stunk of a gassy intellectual dishonesty borrowed and perpetuated, in turn, over two decades, by a loyal troupe of nitwit myrmidons—aside from all that, well, it was a pretty entertaining letter.

In the years since, Urge hasn’t produced a lot of stellar work, though there are powerful songs indeed on “Saturation”’s follow-up, “Enter the Dragon.” (“The Break,” “Tin Foil,” “The Mistake.”) Memories of the band remain strong in the minds of some—witness their opening gig for the Foo Fighters at Wrigley last summer. As for Phair, her ineffable talent only intermittently displayed itself in the other albums from her classic period. (I’m thinking of “Perfect World,” from her third album, “Whitechocolatespaceegg.”) She too was caught up in the indie-cred thing. Everyone had advice for Phair, as I said. Me, I think she should have been a little more commercially pliant at the time—letting someone else direct her videos, rather than insisting on doing them herself, and investing more time in touring, for example. She might have learned something, might have had a more consistent career. She never quite got control of her image, despite even blatantly trying to sell out for a few pop albums in the last decade or so. Her personal web page—in which she stands, mincing, in skimpy underwear—remains an embarrassing testament to this. She became, in a sense, an unreliable narrator, not because she was lying, but because her efforts to maintain or deflect an image sometimes consumed her. A documentary she made on herself—thesis: here are some cool people who think I’m cool, including Ira Glass and John Cusack—is a good example. Her fan base has waned so much that the doc, entitled “Exile Redux,” in contrast to just about every other piece of film made in the last fifty years, can’t be found online.

As for Billy Pumpkin, he was a genuine star for a long enough time to have decisively foiled all his naysayers. I’m sure he’s seen and done things the rest of us can’t even conceive of, and, aside from a few bouts of weirdness, he seems to have handled himself well.

To some, ressentiment remains. In the “Exile Redux” film, for example, Phair lets Albini go off on me one last time: “There was this guy Bill Wyman! He was a gatekeeper! He was, uh, keeping the gates…”

Or something like that.

This debate—underground versus commerciality, integrity versus being a dick, have faded somewhat now. All the groups that want to associate can find their own level on the Internet, and good luck trying to keep something secret. This whole discussion, indeed, will seem jejune, passé, to some.

As for rock—it could be dead. But if it isn’t, those with perspective will note that, every twenty years or so, something comes along. These artists will hear something in their head we haven’t heard before, and undoubtedly feel very lonely and very isolated as they work to make the sounds a reality, but will draw strength from a dream that someone out there wants to hear their music.

Along the way they’ll get called careerists. Or they’ll have some acquaintances, who, vicariously seeing their future through a new hope, will say, “You know what you should do? You should… ”

…and be disgruntled when they are left behind.

By which I mean to say this, an echo of something I once wrote in another article, long ago and right around the time Kurt Cobain decided he wanted to be a rock star: That outside in the dark there are some new rough beasts slouching around, and not even Steve Albini is going to stop them from coming.

After leaving Chicago, Bill Wyman was arts editor of Salon.com and later assistant managing editor at National Public Radio in Washington. He is currently a cultural contributor at Al Jazeera America and has written for the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, New York magazine and the New Yorker.