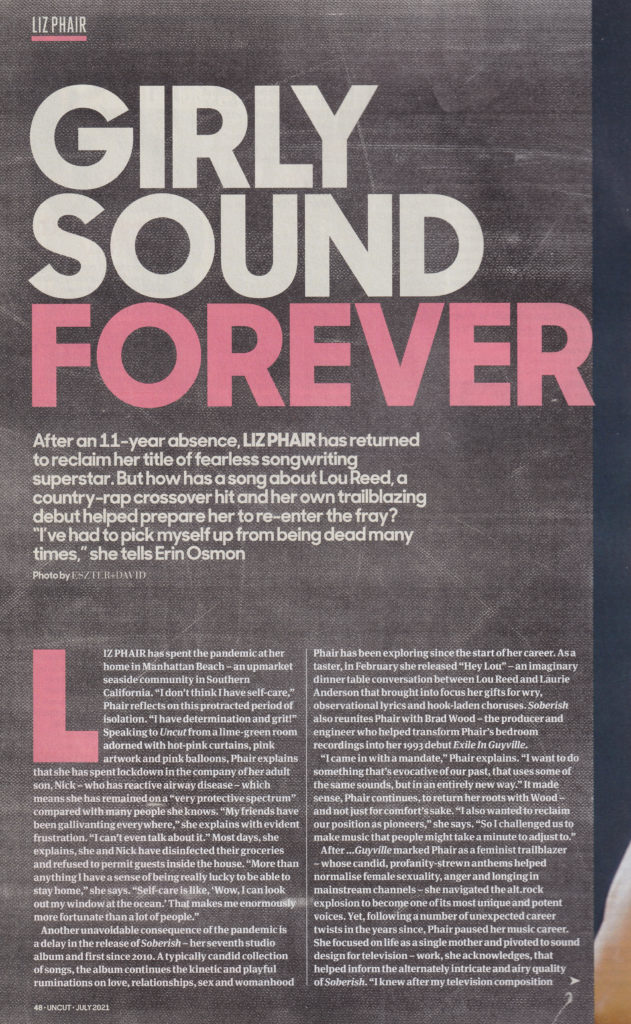

By Erin Osmon

Uncut, July 2021

Liz Phair has spent the pandemic at her home in Manhattan Beach—an upmarket seaside community in Southern California. “I don’t think I have self-care,” Phair reflects on this protracted period of isolation. “I have determination and grit!”

Speaking to Uncut from a lime-green room adorned with hot-pink curtains, pink artwork and pink balloons, Phair explains that she spent lockdown in the company of her adult son, Nick—who has reactive airway disease—which means she has remained on a “very protective spectrum” compared with many people she knows. “My friends have been gallivanting everywhere,” she explains with evident frustration. “I can’t even talk about it.” Most days, she explains, she and Nick have disinfected their groceries and refused to permit guests inside the house. “More than anything I have a sense of being really lucky to be able to stay home,” she says. “Self-care is like, ‘Wow, I can look out my window at the ocean.’ That makes me enormously more fortunate than a lot of people.”

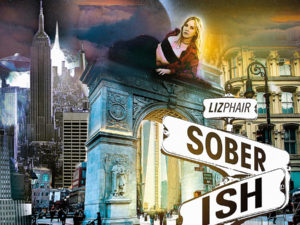

Another unavoidable consequence of the pandemic is a delay in the release of Soberish—her seventh studio album and first since 2010. A typically candid collection of songs, the album continues the kinetic and playful ruminations on love, relationships, sex and womanhood Phair has been exploring since the start of her career. As a taster, in February she released “Hey Lou”—an imaginary dinner table conversation between Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson that brought into focus her gifts for wry, observational lyrics and hook-laden choruses. Soberish also reunites Phair with Brad Wood—the producer and engineer who helped transform Phair’s bedroom recordings into her 1993 debut Exile in Guyville.

“I came in with a mandate,” Phair explains. “I want to do something that’s evocative of our past, that uses some of the same sounds, but in an entirely new way.” It made sense, Phair continues, to return her roots with Wood—and not just for comfort’s sake. “I also wanted to reclaim our position as pioneers,” she says. “So I challenged us to make music that people might take a minute to adjust to.”

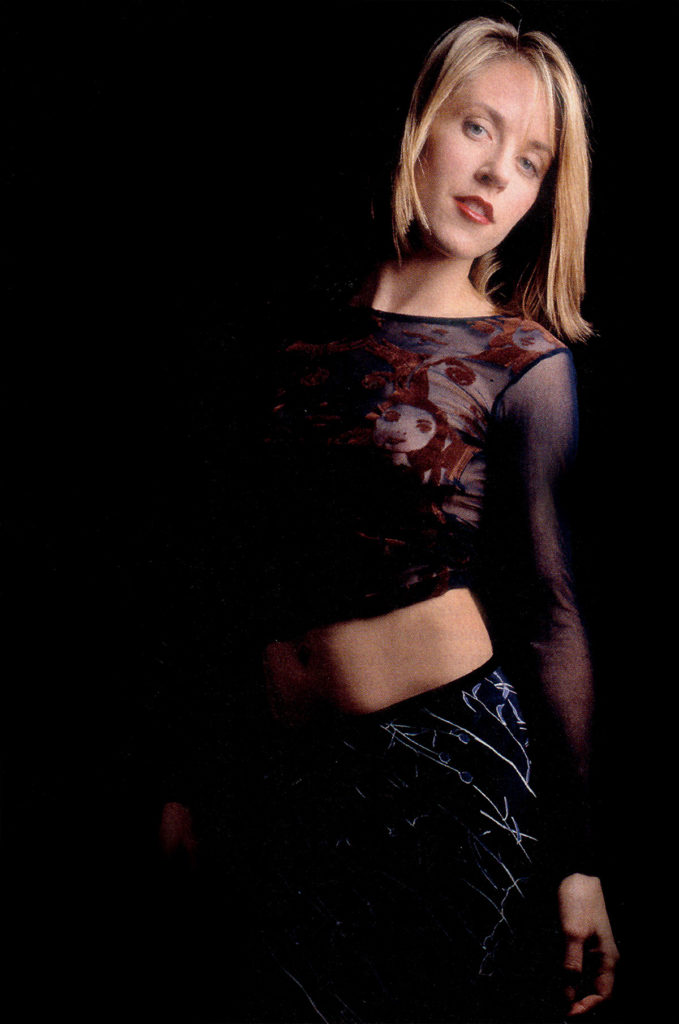

After …Guyville marked Phair as a feminist trailblazer—whose candid, profanity-strewn anthems helped normalise female sexuality, anger and longing in mainstream channels—she navigated the alt.rock explosion to become one of its most unique and potent voices. Yet, following a number of unexpected career twists in the years since, Phair paused her music career. She focused on life as a single mother and pivoted to sound design for television—work, she acknowledges, that helped inform the alternately intricate and airy quality of Soberish. “I knew after my television composition work that I was more interested in complexity, but I also wanted it to be evocative of Guyville, to have the air and spaces somehow,” she says.

In some respects, it seems natural that Phair should continue to refer to her debut album, nearly 30 years since its release. Guyville is a useful barometer against which Phair can continue to judge not just the continuing relevance of its torch-bearing provocations, but also how much she has developed as an artist. Soberish, for instance, features a song called “Bad Kitty,” which traces a complete circle from Guyville to present day. “I don’t live in a world that appreciates me,” she sings. “You could say that I’m ahead of my time.” “I’m grappling with being one of the fallen bodies on the road to progress,” Phair explains. “How many times I’ve had to pick myself up from being dead, like getting knocked down and then getting back up.”

Phair’s musical journey began with a series of lo-fi songs, recorded in her family home in the Chicago suburbs and released under the name Girly-Sound beginning in 1990. The moniker drew a proverbial line in the sand between Phair and the city’s male-dominated underground scene. “I wanted to prove something,” she says. “i was tired of dating guys in bands who told me my taste in music wasn’t very good; that because I liked radio singles, I had no taste; that they were the arbiters of what was cool and what was not.”

Her mission is understandable. For decades, women have navigated music scenes or partnerships where they are wrongfully cast as dilettantes, tenderfoots lucky to learn at the feet of the self-admiring male maestro. Fortunately, Phair’s earliest recordings found support in progressive circles in Chicago and beyond.

“To me they were just incredibly brilliant,” says Tae Won Yu, a visual artist and co-founder of the punk band Kicking Giant, which had ties to DIY punk scenes in Olympia, Washington and Washington, DC. He befriended Phair in New York during the late ’80s, when he was a student at the Cooper Union school and she was an intern for the artist Nancy Spero. A couple of years later, one of Phair’s Girly-Sound cassettes arrived in the post and Won Yu became its de facto PR engine, dubbing and distributing as widely as possible. “For many months I was on a mission, trying to get everybody to hear this thing, just sort of connecting these people.” Won Yu also penned a glowing review of Phair’s Girly-Sound project in the influential fanzine Chemical Imbalance. “Send her some cash for a tape, she’ll probably be up to tape #11 by the time you head this,” he wrote.

In 1991, Phair met Brad Wood—then a neophyte engineer and producer—at Chicago’s Lounge Ax. After listening to a tape of Phair’s home recordings, Wood knew he’d found something special. “It was like a lightning bolt,” he says. “I was just buzzing on my walk home thinking, ‘Oh my God, this is great. What can I do to not screw this up?'” Phair and Wood began tinkering in his Wicker Park recording studio in late ’91, while local labels including Feel Good All Over and Minty Fresh began to express interest in Phair’s music.

“There were a lot of people circling at that time,” Phair says. “We felt cool because we were the artists… We kind of had this attitude like, ‘If you want to buy us dinner, fuck it, we’ll take it.'” Amid the groundswell, Phair rang one of America’s most celebrated independent record labels. “Minty Fresh wanted to sign me, they had taken me out to dinner or something,” she says. “So I was like, ‘I’ll give you a single, but I’m going to sign with Matador.'”

It transpires that Gerard Cosloy, co-owner of Matador, had already read Won Yu’s review in Chemical Imbalance. Intrigued, he encouraged Phair to send along some of the demos she’d been working on with Wood. “We thought the songs were fantastic, really personal, very direct, elemental but really well written,” he recalls. “So without ever having seen Liz perform, or ever having met her, we almost immediately said, ‘Hey, let’s do this.'” According to Phair, Matador’s interest helped spur a feeding frenzy among her local scene. “There was this whole movement of Chicago becoming the new Seattle,” she says. “All the major labels wanted to come to Chicago and buy up all the bands like, ‘The crop has ripened, we must go pick it.'”

Released in June 1993, Exile in Guyville went on to sell more than half a million copies. Its fiery, earnest and messy accounts of the female experience proved empowering to many women and girls. But it wasn’t without its detractors. “Liz Phair is Rickie Lee Jones (more talked about than heard, a persona completely unrooted in substance, and a fucking chore to listen to),” wrote Steve Albini in a letter to the editor of the Chicago Reader. His words were reflective of a broader, often implicit resentment coursing through the scene—”Guyville.” Today, however, Phair has a sanguine response to this male-driven backlash. “Inter-family squabbling among music people kind of makes me feel at home,” she says. Exile in Guyville was more important and enduring than those opinions, anyway. “I feel so grateful that I have this strong piece of art that has basically given me a whole lifetime of a career,” she adds.

Phair has built her career on defying expectations. She followed Guyville with Whip-Smart (1994) and Whitechocolatespaceegg (1998)—both recorded and co-produced with Wood. But tiring of the parochial, patriarchal confines of indie-rock, she pursued crossover collaborations, singing low harmony on Sheryl Crow’s 2002 megahit “Soak Up the Sun” and co-writing her biggest single, 2003’s “Why Can’t I,” with early-2000’s pop juggernaut The Matrix. The latter track appeared on her self-titled pop album—an evident departure from her first three records, it horrified indie-rock’s gatekeepers and famously earned a 0.0 rating on Pitchfork. “The writer later apologised to me, on Twitter I think,” Phair says. “It was sweet but unnecessary, because I thought it was kind of funny. Coming up in the ’90s, it was pretty rough and tumble. Fanzines could be vicious by design. It was almost a constant roast.”

Then, in 2018, Phair oversaw a deluxe reissue of Exile in Guyville, which includes three of her legendary Girly-Sound tapes. For Phair, revisiting the material proved revelatory. “It was so fun to put out the boxset, because Girly-Sound is very pop,” she says. “There’s a lot of pop in there and the overtly ridiculous stuff I was doing before Guyville. That was its own zone, just like Guyville was its own zone. Then the pop record [Liz Phair] was in its own zone. Each album to me is separate and has its own world-building element.”

After aborted sessions with Ryan Adams, Phair surfaced again in 2019—once again revisiting her past in Horror Stories, a memoir depicting her life in a series of fearless, frank essays. “I was certainly an asshole in the ’90s,” she admits. “My memoir was sort of my mea culpa, going through the things I carried with me as shame from my behaviour.”

At the same time, these acts of reflection—combined with a wide-open contemporary climate, where rockist attitudes are passé—has proved fertile soil for the making of Soberish. Today, more than a decade since her last full-length album, she’s thrilled to re-emerge amid what feels like a positive cultural sea change. She talks about the current proliferation of self-assured female singer-songwriters—artists like Lana Del Rey, Weyes Blood, Phoebe Bridgers, Aldous Harding and others. “I walked into my manager’s office and said, ‘This wave is happening, and I want to be part of it,” she explains. “This is what I was longing for when I was exiled in Guyville. This is what wasn’t there.”

While Soberish finds Phair revising many of her favourite themes with characteristically bracing honesty, the album is very much its own entity. Its complex emotional states are the product of Phair’s accumulated life experience. “I was thinking, jealousy, about my younger self,” she explains. “How it was easier when I was younger to point the finger and say, like ‘You’re wrong, you fucked it up!’ I don’t have that in me, authentically, as much any more. I have it for politics. But I don’t have that sense any more that human interactions are as cut and dry.”

The album depicts events in Phair’s personal life as well as more speculative ruminations on love and relationships. These matters of the heart stretch from Los Angeles to Chicago, to New York and Paris and beyond—many of which are represented on the album’s cover, a montage of city landmarks designed by Phair’s son Nick. “We work together very well,” she adds. “He’s worked as an engineer on some of my music. He did the art for the album. He’s been integral in allowing me to work from home.” To set the scene—both emotionally and geographically—the catchy opener, “Spanish Doors,” details the unraveling of a relationship. “I’m slowly disappearing behind out Spanish doors / The ghost I see in the mirror doesn’t smile any more,” Phair sings. During the chorus, the narrator’s internal voices overlap—one anxious and the other resigned—creating a fascinating internal dialogue that exposes the many anxieties of a break-up.

The title track itself relays the messy anticipation of an on-again off-again love affair. It exemplifies Phair and Wood’s working practices—an unself-conscious willingness to experiment, to add or subtract in unexpected ways. “The song was really not working until we pulled out my guitars,” Phair reveals. “That awkward anticipation of meeting someone you know you’re going to sleep with but you’re really nervous because you haven’t slept with them many times… That suddenly just came alive. That song hang you in that space of anticipation and awkwardness and vulnerability in a way that we just had to take out all the crunchy guitars.” Elsewhere, Phair explains, she gave specific instructions to Wood about how the songs were going to be constructed. “I said, ‘None of the songs are gonna be traditional arrangements. I’ve got some bridges as the second verse on at least five of them. But I don’t want the listener to focus on that. I want it to flow right past you.”

In the years since she and Wood tracked Exile in Guyville, Whip-Smart, and Whitechocolatespaceegg, Phair says they’ve both grown as artists and technicians. She’s toured the world and worked in some of the biggest major-label studios, while Wood has recorded, mixed or produced hundreds of records, including hit albums by Pete Yorn, Ben Lee, Placebo and others. Their interest in quirky, complex arrangements that burrow into one’s consciousness is evident throughout their latest collaboration, and they are both quick to point to one song in particular as inspiration. “She spent an inordinate amount of time talking about Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road’,” Wood says. Phair was impressed by its rule-breaking, that something so unconventional and unexpected could become such a cultural phenomenon. “It was like permission to blur genres and arrange unexpectedly,” she says. “I want more room for weirder songs to rise to the top.”

Wood was struck by its layers, particularly the song’s clever use of a melancholic Nine Inch Nails sample. “As a result, we didn’t shy away from using loops,” Wood says. “We used found sound, stuff we sourced from the internet, maybe something she played, to start as the inspiration point. I’d manipulate it and find a tempo, then we might replace it or turn it off eventually.” Audience clapping, for example, shaped the framework for “Hey Lou.” It’s typical of how the pair have worked previously, seeking out unlikely elements to bring additional textures to their collaborations. In the early ’90s, for instance, they created analogue tape loops by sampling the television in Wood’s studio, an ancient thing with rabbit ears that only picked up public television and a Korean cable access station. “There are a lot of Korean voices on Guyville and a few on Whip-Smart,” Wood says. “The song ‘Whip-Smart’ is based on a drum loop I played and Liz overdubbed to.” For Soberish, the pair worked in fits and starts over the course of a year, taking their time to examine and deconstruct the songs. “Brad and I are very compatible in the studio,” Phair says. “We’re painting with sound.” When Phair learned that the album’s release would be delayed owing to the pandemic, she even wrote some new material to ensure its spirit was fresh and representative of Phair in 2021. “I tried to anticipate where my mind was going to be,” she says. “That was a fun game!”

Reflecting on the winding path of her career, Phair is well aware of the challenges posed by releasing a new record 30 years in. “There’s a scary thing that happens toward the end of your career where it’s like, ‘How many more chances am I going to get to be relevant and current?'” she explains. “As opposed to, ‘How am I going to get in the door?’, now it’s, ‘How am I going to avoid getting pushed out the door?'” The entertainment industry’s ill regard for women over 40 is well documented, but Phair says strong female friendships and alliances have helped her along the way. This is particularly true of some of her peers. Last June, Phair was set to join Alanis Morissette on a North American tour celebrating the 25th anniversary of Morissette’s Jagged Little Pill album. “She came in with that offer at a moment that felt very much like a woman supporting a woman, kind of a beautiful generosity of spirit,” Phair says. “I really needed something to give me some wind beneath my wings.” Unfortunately, that lift was postponed amid the pandemic. “I had been dreaming about my ultimate tour and then I had it,” she adds. “Losing that was heartbreaking.”

“I was certainly an asshole in the ’90s.”

Liz Phair

Fortunately, Phair rejoins Morissette this summer and autumn, opening along with Garbage. Phair says playing premium theatres and outdoor pavilions with two women she admires feels right for her station in life. “I need to be at a level where touring is comfortable for a woman my age because there’s a certain amount of roughness and toughness and hardness about it, and I’d like to get just above that cloud cover,” she says. “And I feel like after 30 years in the career, I should be able to get above that cloud cover, and tour more comfortably and just feel safe.”

The hook-filled soul-baring of Soberish also provides plenty to celebrate. The album signals a career high point from a mature artist clearly operating at a creative peak, a reclamation of Phair’s throne that also pushes past the boundaries of expectation. “All I could do was be true to myself and show my mastery at this sort of older level, while trying to also be reflective of what’s happening now,” she says. By distilling complex inner worlds into perspicacious and slightly askew three-minute morsels, Phair has brought her ’90s-era style sharply into the present. “The thing I’m most proud of with Soberish is that we set a directive—it was hard to find at first—but then we clicked in and could really go,” she says. “We’re willing to throw something in you wouldn’t think would work and pull something out you think should’ve been there. And I think we’re pretty good at it.”

Phair Play: A Liz Phair’s buyer’s guide

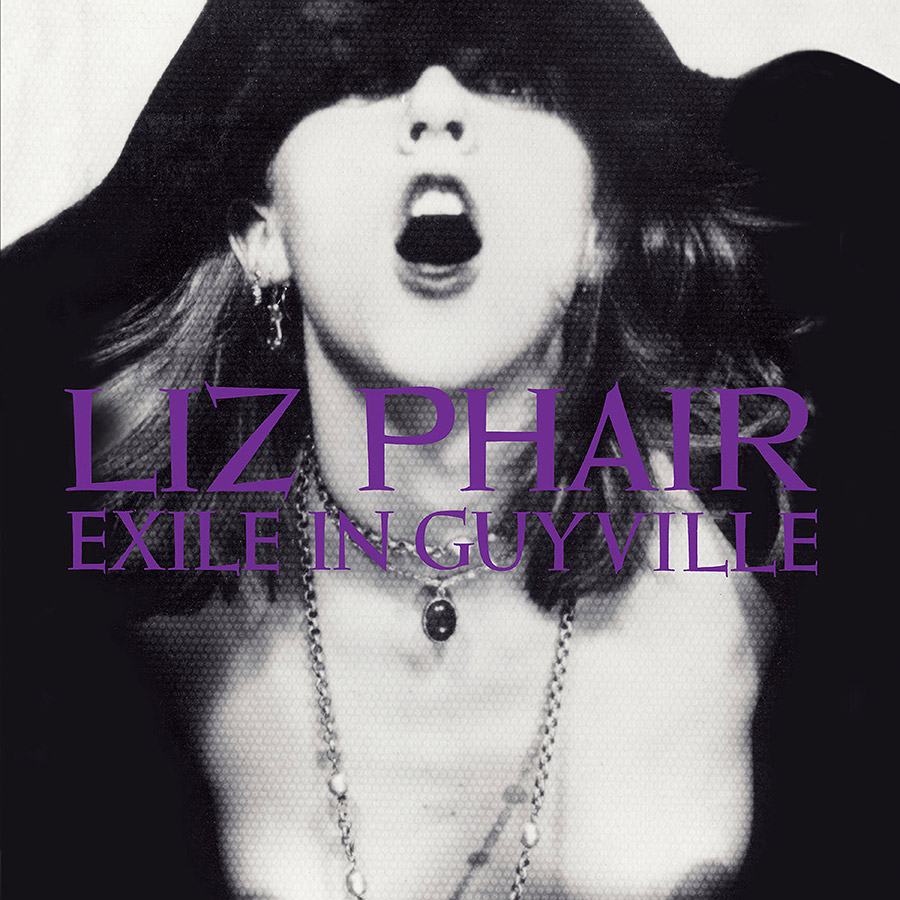

Exile in Guyville

Matador, 1993

Her audacious debut—double album, no less—introduced Phair’s unrestrained confessionalism to the wider world. But she was no overnight success. Phair had been defining and refining her music for years through her lo-fi Girly-Sound cassettes—released for the first time with the 2018 Guyville reissue.

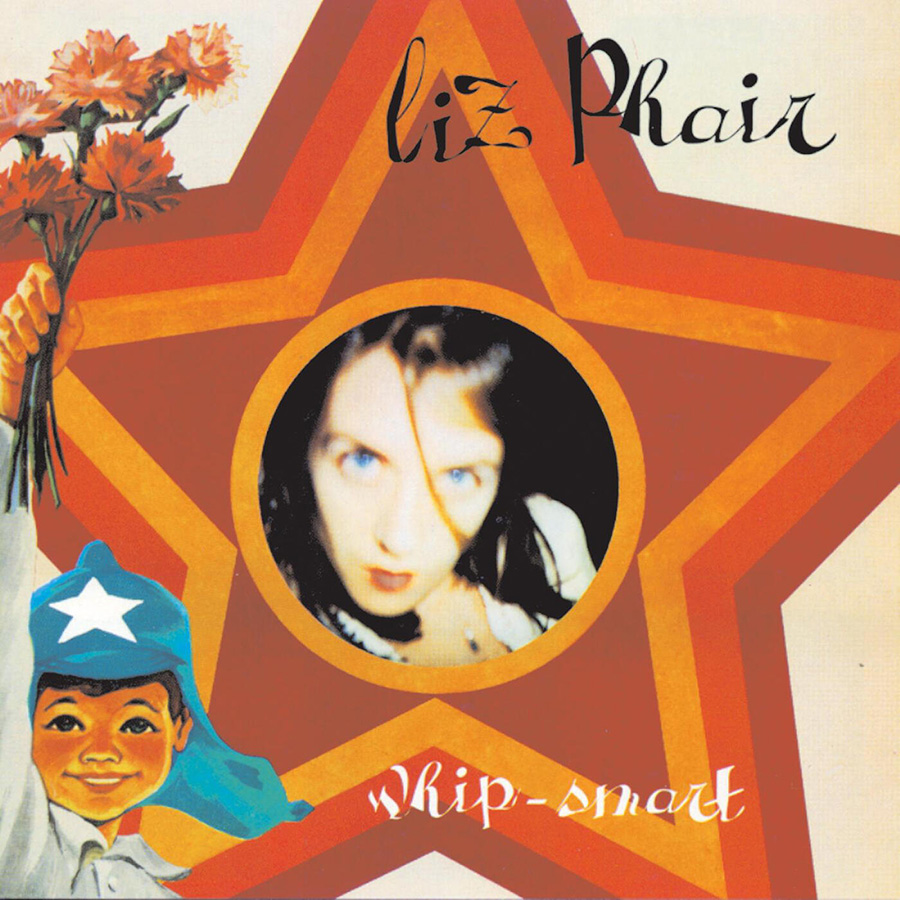

Whip-Smart

Matador, 1994

Guyville’s well-received 1994 follow-up, Whip-Smart is a little slicker and a little more complex, reflective of the deluge of experience that comes with navigating a hit record. It includes the hit “Supernova” as well as the charming and infectious title track.

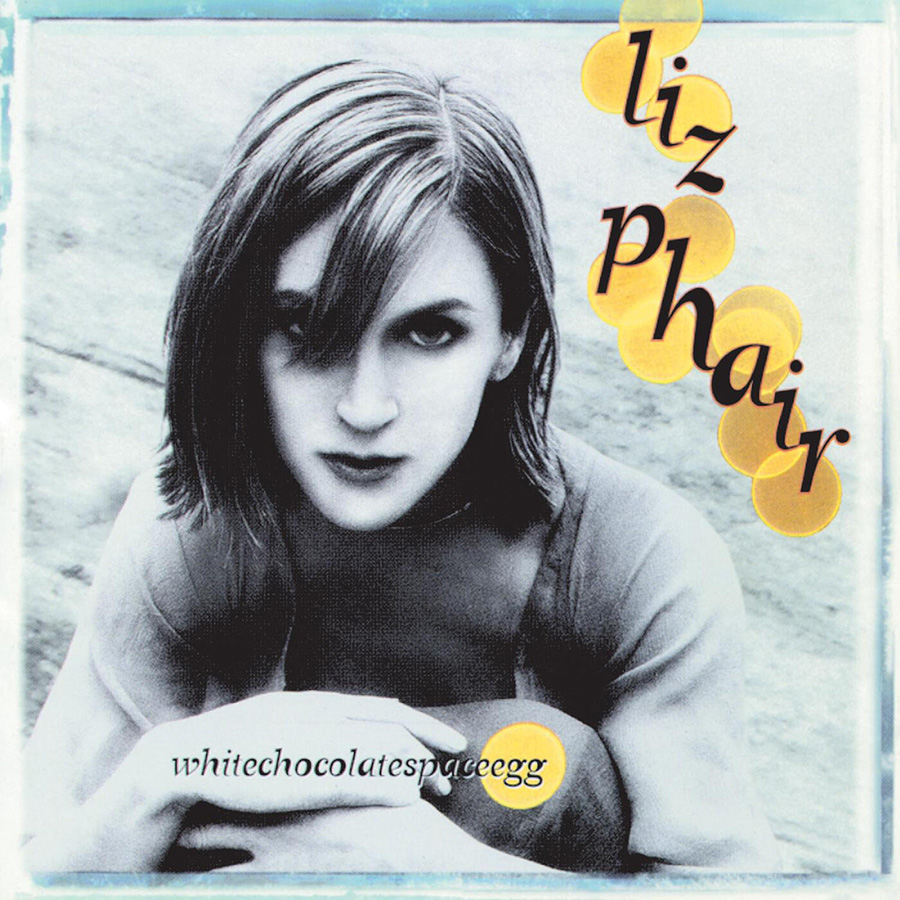

whitechocolatespaceegg

Matador, 1998

Her third is strong, but began to divide fans for its multi-pronged approach—by turns stripped down and intimate, blown out and full throated or thoroughly poppy. Highlights include “Baby Got Going.”

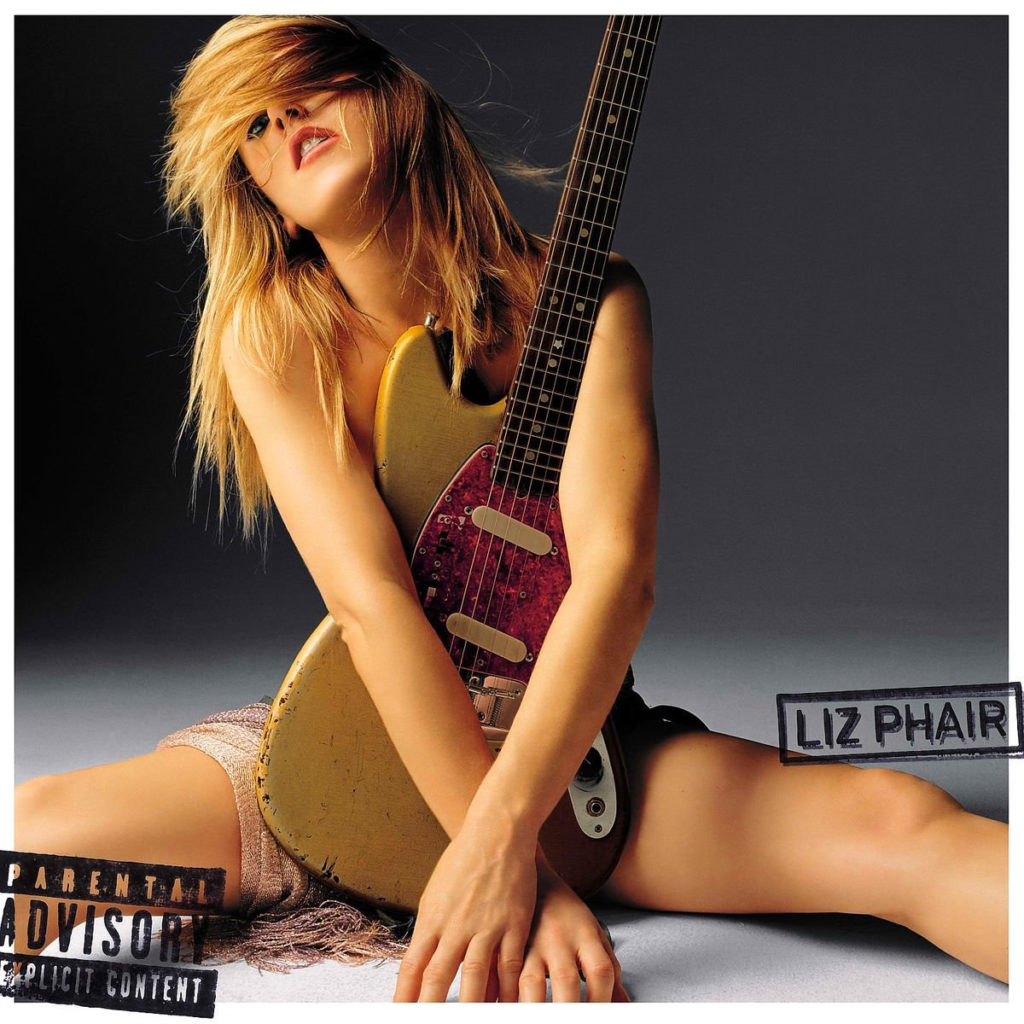

Liz Phair

Capitol, 2003

This 2003 pop-crossover either sunk or catapulted Phair, depending on who you ask. Old fans and indie gatekeepers hated it. Fans coming late to Phair, meanwhile, loved it. Or rather, they loved “Why Can’t I?”—a single co-written with mega-pop producers The Matrix.

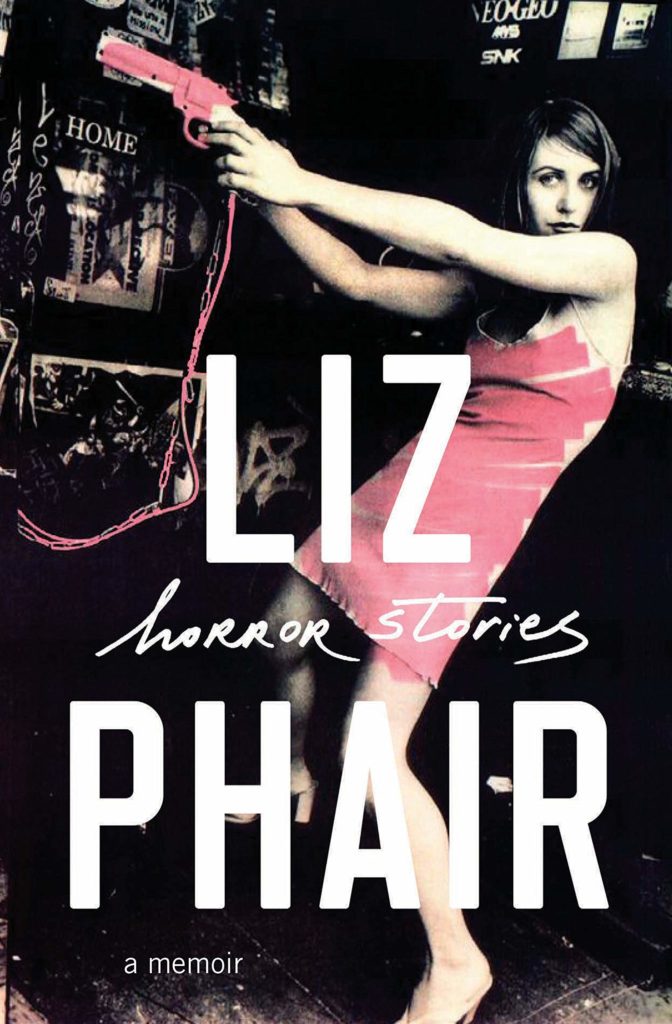

Horror Stories

Random House, 2019

Phair’s engrossing memoir litigates her past without exempting herself from the scrutiny. Like many of her songs, it revisits some of Phair’s most shocking, vulnerable and unbelievable moments, from hilarious and heartbreaking romantic encounters, to sexist music-industry experiences.

A Phair selection of female artists

“I’m so inspired by how fully formed all these female artists are,” Phair says of the current wave. “They’re not just fronting a band. They’re not just showing up in the studio as the person who wrote the songs. Sometimes they’re recording the whole album, they’re designing the visual, they’re presenting themselves on stage in a theatrical manner playing multiple instruments.” So who are her favourites? “All you have to do is look at my Twitter,” she says, “Because I pick up like a new female artist almost every day. Just like, click, click, click.” She isn’t lying. Phair follows many contemporary female musicians from Neko Case to Aldous Harding and Best Coast frontwoman Bethany Cosentino.

“I first heard Liz in high school and was immediately drawn to how unique her style was,” says Cosentino. “Both her voice and her songwriting. I’ve always loved really raw, personal songwriting that feels like storytelling, and you definitely get that out of a Liz Phair song. Writing really personal, somewhat grungy pop songs is something I’ve done for over a decade in Best Coast, and I definitely would say Liz has been a big role model for me in doing so. There’s something really special about her songwriting; it doesn’t feel untouchable or hard to understand, it’s digestible and catchy and it’s inspiring to see how much she’s evolved over time and how she’s taken risks and stepped outside of the box as an artist.”

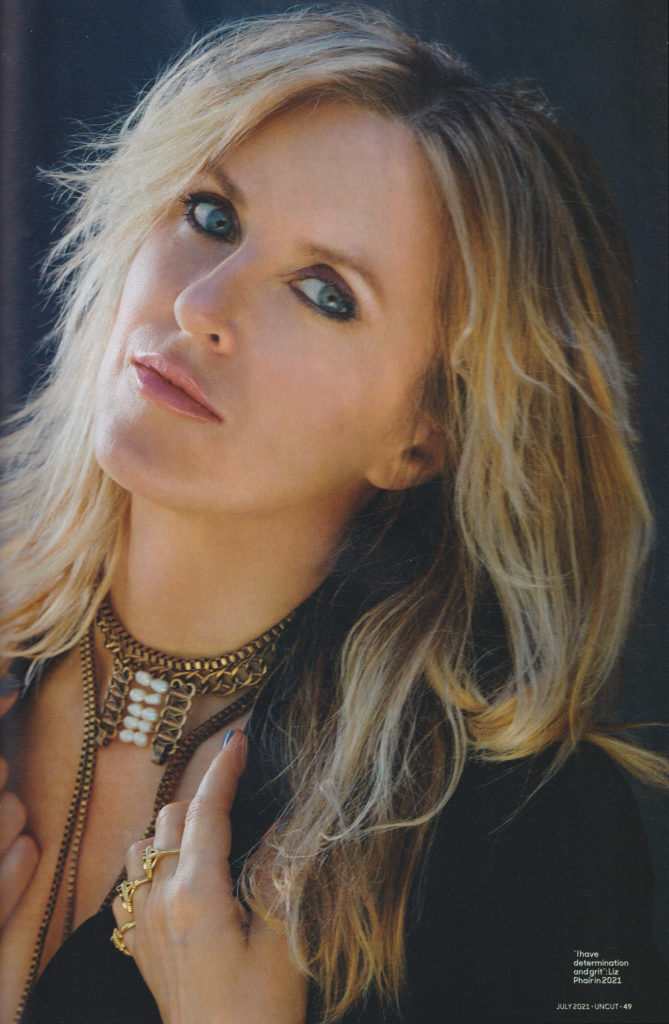

Featured Image: Photo by Eszter+David