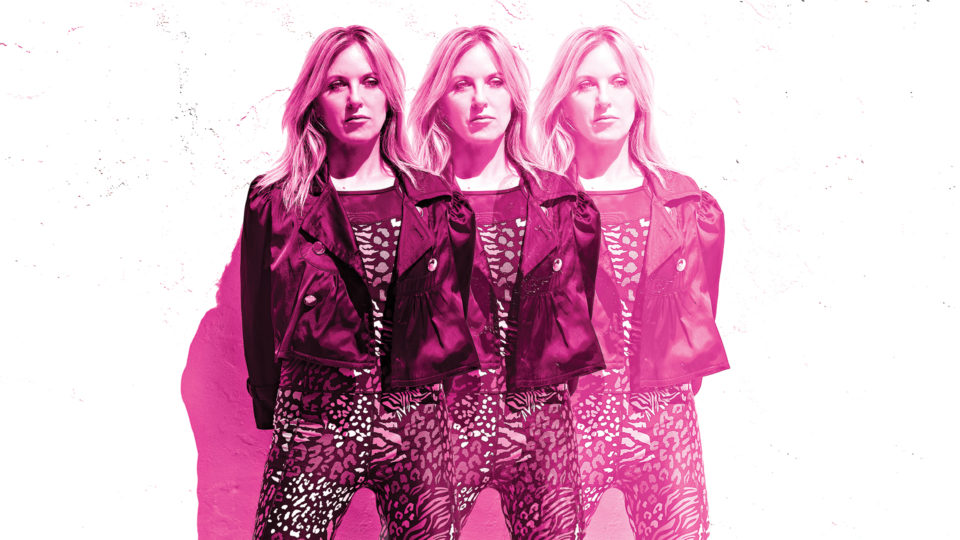

By Geoff Edgers

Washington Post, May 27, 2021

It’s convenient to blame 2003 for Liz Phair’s musical silence.

That’s when she put out her most sugary pop record, an album so slick that it both blasted up the charts and infuriated the indie rock kids who had once worshiped her. The bedroom pop queen had become the wicked witch of the Top 40, “an embarrassing form of career suicide,” as the New York Times put it.

In this convenient narrative, an emotionally battered Phair withdraws to her Malibu mansion with the complete “My So-Called Life” on VHS and abandons pop music.

“But that’s not what happened to me,” Phair says in a recent Zoom interview from her home in Los Angeles. “Did 2003 make me want to break? Yes. But so did 1998 and so did 1997 and so did 1995. They all made me want to take a break because the music business is so screwed up.”

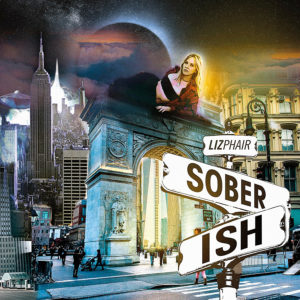

It is almost summer and Phair is doing this interview because “Soberish,” her first album of original songs in more than 10 years, will be out June 4 on Chrysalis Records. The album marks a reunion with producer Brad Wood, her musical partner on her acclaimed debut, 1993’s “Exile in Guyville,” and its follow-up, 1994’s “Whip-Smart.” “Exile” charted the emotional terrain of a supremely 20-something universe with an unaffected, intimate charm. “Soberish” is both a throwback and a reinvention. The songs are stripped of the gloss of her Capitol Record debut but it isn’t jangly, lo-fi pop. “Soberish” is also sung by an adult. It’s a relationship record where the awkward spaces are framed by experience and perspective, not post-dorm fumbling.

“Everyone’s got a maze inside their heart,” she sings on the title track. “The best we can do is pick a place to start.”

“Yes, I look at the bad stuff and I think of the good that came out of it, and only a 53-year-old would do that because you wouldn’t have had the hindsight to do it at a younger age,” says Phair, who turned 54 in April. “It’s not magical. It’s because you decide not to be defeated. You decide to take what you’ve got and turn it into something. ‘Soberish,’ to me, is a lot about the beginnings of things, the endings of things, the state between two states. . . . I’m interested in transitional, undefined territory, and I think that is an older person’s game.”

In conversation, Phair can take a single moment and examine it from different angles. Her triumphant, indie debut was, in fact, not a particularly joyful moment, but packed with anxiety and trauma “and the closest I ever got to being anorexic.” Her fall in the early 2000s was not all terrible: The pressure of touring a major-label record pushed her to get better — “it probably saved me as a performer,” she says — and introduced her to a different audience. She still performs some of those songs.

And as “Soberish” arrives, Phair is still dealing with her place in the #MeToo movement. In her 2018 memoir, “Horror Stories,” she detailed her experiences with bad men, from the married college internship supervisor who flashed a pair of earrings that could be hers if she slept with him to the record-label president offering $5,000 to make her his live-in mistress. These days, she braces for every interview to include a question about Ryan Adams, the alt-country train wreck whose 2019 scandal derailed a project they were working on. She also brings up her continued disdain for Andy Slater, a former Capitol Records chief executive whom she already took musician revenge on in 2010 with the song “And He Slayed Her.”

For all she disliked at Capitol, the experience did inspire her to start a still-unpublished novel about the music business, which is tentatively titled “Side Man.”

“Now I’m going to be working as an author,” she says. “I could not have had that if he didn’t push me to such an extent that I said to myself, ‘What can I do that no one has control over?’ ”

Phair never planned on making it to the cover of Rolling Stone.

She graduated from Oberlin College in 1990 with a degree in art history and studio art. The following summer, she made a series of homemade recordings, known as the “Girly-Sound” tapes, and ended up with a deal with Matador Records. The indie label had already released influential albums by Teenage Fanclub and Pavement. But 1993’s “Exile in Guyville,” a response to the Rolling Stones’ “Exile on Main Street,” would eclipse everything. It featured Phair’s stylishly flat delivery, soul-bearing lyrics and a blurry, nipple-bearing photo of the artist on the cover. “Exile in Guyville” landed atop most critics-best lists and made her a star. It also created unexpected pressure.

Men who had heard her sing boldly about sex didn’t hesitate to proposition her. She headed out on tour even though she found it terrifying. Phair’s next two albums were solid, if not as successful, and her six-year marriage to film editor Jim Staskauskas fell apart. But she remained a valuable commodity. In 1999, when Matador dissolved a partnership with Capitol, the major label demanded her contract as collateral.

It wasn’t until 2003, five years after her last record, that Phair emerged with the self-titled album that included collaborations with the Matrix, fresh off their smash production work with Avril Lavigne. The album went gold and featured the hit “Why Can’t I?” It also earned Phair the worst reviews of her career.

But Phair says that what led to her music exile was more the tiring cycle of recording, promoting and touring, and also raising her son, Nick, who was still in elementary school. So she began scoring television shows, including writing the theme songs for CW’s reboot of “90210” and NBC’s “The Weber Show.” It was only when Nick headed to college that Phair began to think about reviving her career.

In 2016, she did her first big tour for the first time in years, opening for the Smashing Pumpkins.

And then, in January 2017, Ryan Adams tweeted photos of Phair and bassist Don Was in the studio and announced “Today we begin the new @PhizLair double album!!!”

In “Horror Stories,” Phair writes of her frustration with that tweet — “milking my name for all it was worth.” Because after the tweet, work on the album sputtered. The idea had been to do a song-by-song response to the Beatles’ “White Album.” Then, in 2019, the New York Times reported on allegations against Adams, including harassment of aspiring musicians and sending sexually explicit messages to an underage girl. (Phair, in her memoir, said that he propositioned her at one point, but that she brushed him off.)

And somewhere around that point, Phair thought of Brad Wood.

They were a perfect music couple in the early ’90s. Wood co-produced and played drums and bass. (Casey Rice played lead guitar on several tracks.) Phair’s shoe box, four-track sound bloomed. But in 1994, Phair canceled a band tour for “Whip-Smart” that was supposed to include Wood, and started working with other producers for 1998’s “Whitechocolatespaceegg.” Wood and Phair reconnected socially a few years later, after they had moved to Los Angeles, setting up playdates with their children.

The idea of working together again didn’t emerge until she embarked on 2018’s “Girly-Sound to Guyville: The 25th Anniversary Box Set.”

“I was encouraging her to give that a go,” says Chris Lombardi, Matador’s co-owner, who had kept in touch with Phair over the years. “He was able to pull out some of the best aspects of Liz and it was sort of a nurturing environment where she could be herself and not feel pressured to spend a bajillion dollars.”

Wood, whose post-Phair career included producing albums for Ben Lee, the Bangles and Veruca Salt, was not sure it would work.

“I attribute a lot of luck to our success in 1991 and 1992,” he says. “Circumstances were right and we were of a specific age range where you could dedicate resources of time and energy into making a record that none of us had in 2019. How I play drums, I thought, is different and how I record is really different and she’s not the same person. A lot of it is I couldn’t predict how she would approach writing and what she would write about.”

One of the first songs they worked on was “Hey Lou,” an imagination of the relationship between the late Lou Reed and Laurie Anderson. Phair referenced his drug use and time with Andy Warhol and plugged Anderson’s biggest hit. (“Oh Superman, I’ve done as much as I can/You’re not the life of the party.”)

(Anderson, through a spokesperson, said she wasn’t aware of the song and declined to comment on it.)

But most of “Soberish” would cover more personal territory. “Horror Stories” offered an unvarnished, unforgiving view of relationships, infidelities and false expectations. “Soberish” would return to that area.

In “Spanish Doors,” the album’s opener and one of the few songs with the jangly guitar reminiscent of “Guyville,” she sings, “I don’t want to see anybody I know/I don’t want to be anywhere that you and I used to go.”

On “In There,” a ballad with a trip-hop beat and hand claps, “I can think of a thousand things that are wrong/I can think of a thousand reasons why you and I can’t get along.”

And on the title track, she tells of a meetup at New York’s St. Regis Hotel, a relationship she terms “a fresh kill,” in an interview.

“I fictionalized it,” she says. “I disguised it. But the person I write it about will know. Everyone who’s written about on this album should know it’s about them.”

There is clearly a sense, for Phair, that she wants to give her fans what they want: pop songs she didn’t dash off, that sound like her while not merely cribbing from “Guyville.” On the title song, they started with her distinctively strummed guitar. But one day, as Wood was trying to isolate the bass on the recording, Phair overheard a stripped-down version of the song. It worked. They sped up “Soberish” and ended up peeling back her guitar on several other songs.

Does she regret that it took so long to get to her seventh album? Does she wish more Liz Phair records were in the world? A couple of years ago, she met Snail Mail’s Lindsey Jordan, a longtime admirer.

Jordan told Phair she felt worn out. Snail Mail’s “Lush” had come out in 2018 when she was not yet 19, and she’d been working ever since.

“The biggest takeaway from our conversations was about not slowing down,” Jordan says. “She warned me that you have to kind of stay on your feet, work really hard and how breaks are kind of rough on your career.”

Phair listens to that quote and laughs at the idea that it contains a larger lesson about her own path. That advice was for Jordan. It was not for Liz Phair, she says.

As for her own legacy, she says she has one more album in her. And then, who knows?

Featured Image: Photo by Eszter+David