By Rob Sheffield

Rolling Stone, June 22, 2023

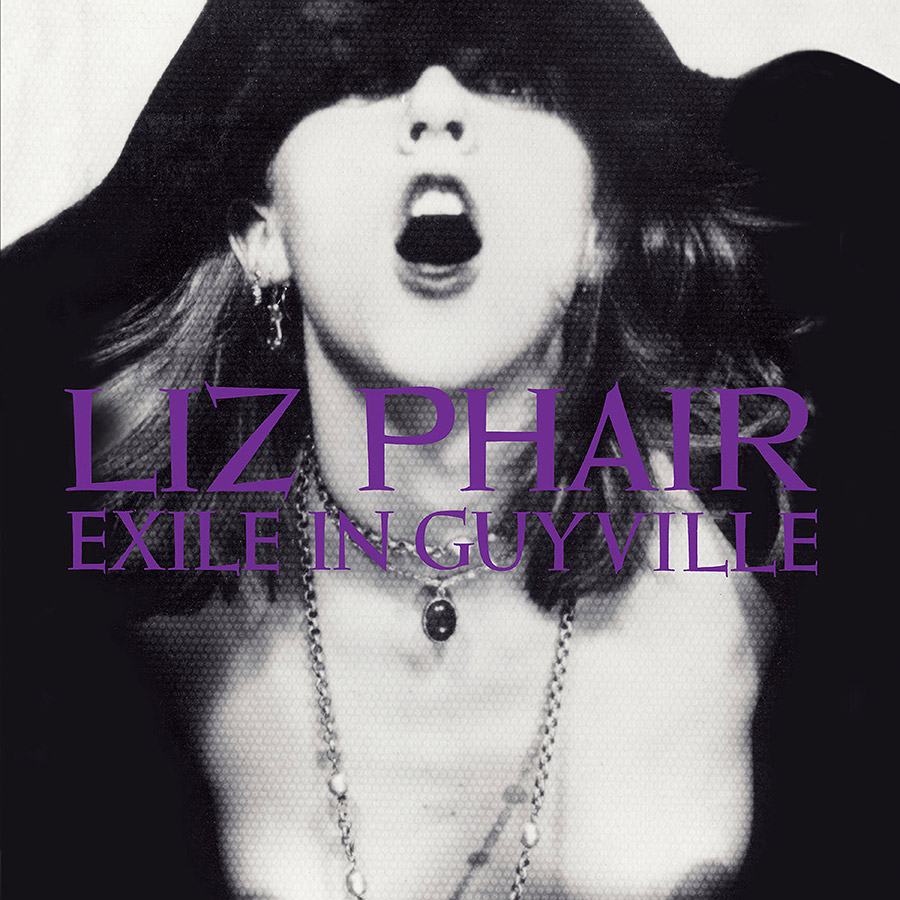

Thirty years ago, Liz Phair released her indie-rock masterpiece Exile in Guyville, on June 22, 1993. It’s a massive moment in the history of the Weird Girl canon. Liz was just an ordinary twenty-something geek in the Chicago indie scene of Wicker Park, going out every night to see hipster bands, hanging out in dive bars, and getting her heart broken. It was a Guyville, where she was just another girl. But she had a secret that nobody knew: she was writing songs about the whole experience. And she was singing them into her four-track in her bedroom, just Liz and her guitar.

She started putting out her songs on homemade cassettes, hiding behind the name “Girly-Sound.” But a funny thing happened: those tapes got passed around, because virtually everyone who heard this music taped it for their friends. I first heard Liz Phair in early 1992, when a friend put “Flower” on a mix tape. It was so weird to hear this flat, nasal, every-girl voice sneering through a cloud of tape hiss, her voice on fire with sarcasm and lust, plucking her guitar, singing her abrasively witty one-liners like “I’ll fuck you and your girlfriend too.” Nobody had any idea who this “Girly-Sound” was. But we all wanted to hear more.

She turned these songs into Exile in Guyville, one of the best rock albums ever made. “I had never recorded before,” Phair told Rolling Stone last year.

“I had never performed onstage before,” she added. “All I had done is play songs in my bedroom.” But 30 years later, Exile resonates more than ever, with classics like “Fuck and Run,” “Mesmerizing,” and “Divorce Song.” She gets real about heartbreak, sex, anger and independence, in her extremely non-rock-star Midwestern mumble. Long before the word “fuckboy” existed, Phair was ripping the whole species to shreds.

She’s celebrating the anniversary with a previously unreleased version of “Miss Lucy,” recorded during the Exile sessions but left off the album to make room for “Flower.” It’s a Girly-Sound gem based on the classic jump-rope rhyme, unearthed and remixed by Phair and Brad Wood. She’s also doing a 30th Anniversary tour this fall, hitting the road with her band to play the whole album and other hits. She also appears on the upcoming Nick Drake tribute The Endless Coloured Ways, which drops on July 7, singing the seductive Pink Moon classic, “Free Ride.”

Nobody had heard anything like Exile before. Phair was a self-invented rock star, a fan who crossed the line just by picking up a guitar and writing her own songs, flaunting her raw emotion, wiseass humor, fearless honesty and merciless eye for detail. It was part of a Nineties feminist explosion in rock culture— 1993 also had brilliant records by PJ Harvey, The Breeders, Bratmobile, Helium, Bikini Kill, L7, and so many others. She designed Exile as her song-by-song answer to the Rolling Stones’ 1972 classic Exile on Main Street. Yet she sounds like her own unfiltered self, stumbling and raging through her twenties. “It’s that classic age of disillusionment and fury,” Phair told me. “And I think Guyville has a lot of that. If you aren’t pissed in your twenties, you’re not paying attention.”

But Guyville is more influential than ever these days, especially over the past decade. Like so many of the girl characters in these songs, Exile has had a wild and intense ride in its twenties. Back in 2008, when Phair released a 15th Anniversary edition, nobody noticed. She made a documentary on the album, Guyville Redux, but nobody watched. The culture was not really checking for rebellious women with guitars in 2008. (Those were different times.)

But the album has taken on a new life, reaching a new generation of fans. Her label Matador released the 2019 box Girly-Sound to Guyville, finally collecting the legendary 1991 Girly-Sound tapes. Millenial and Gen Z fans get Phair on a deeper level than anyone else ever has. For young songwriters, Exile represents the standard of emotional realness they want to reach.

Phair figured nobody would ever hear these songs — but that’s why she felt so free to get personal. “I’m singing entirely from the place of the privacy of a bedroom,” Phair says. “I think that’s one of the tricks of Guyville — in my mind, there was no question that I would ever get up onstage. ‘I would never do something like that. I have no desire to do that. What a terrible idea.’ So most bands would picture performing their songs live for people. But this album was written entirely from the point of view of the person that’s never going to tell this to anybody.”

It was a shock for Liz — and the Guyville scenesters she was singing about — when her little DIY project blew up. “I knew that a certain amount of people were going to listen to this record,” Phair says. “I thought maybe, in a crazy fantastical scenario, 1,500 people would hear it, you know? I felt safe knowing that my family and friends were not ever gonna hear this record. I thought I was just speaking to like-minded people, rather than, ‘Check out what’s wrong with this chick in the Midwest! You won’t believe it!’ Which is what some of my cousins were basically saying. They were like, ‘Jesus, Elizabeth has gone off the rails!’ There was this sense of my life blowing up because of a record. And that, I did not intend to take on.”

In her 2008 doc about the album, the funniest line comes from Urge Overkill’s Nash Kato, the biggest rock star in this Wicker Park scene and a muse for the album. (He took the flirty photo-booth cover shot.) He admits he had barely any idea who this Liz was. “She writes songs? She has a last name?”

Exile sold 200,000 copies at the time, on an indie label, which just didn’t happen at the time. Radio and MTV ignored it, although “Never Said” got a few spins on 120 Minutes. But it became a surprise worldwide smash, just because it hit a nerve with so many people. For many of us, it felt like this was an album we’d been waiting to hear our whole lives. But as Phair says, “I felt like I’d been waiting to SAY these things my whole life.”

She revels in her role-playing, relishing her Mick Jagger cosplay, from romantic yearning to cold-blooded lust. In “Girls! Girls! Girls!,” she’s a sexual conquistador, leering, “I take full advantage of every man I meet.” But she places that song right after “Fuck and Run,” where she confesses, “I want all that stupid old shit like letters and sodas.” “I wanted to show contradiction,” Phair says. “I wanted to carve out space for the complex woman, consciously. Which is weird, but I took that very seriously back then.”

One of the people who flipped for the original Girly-Sound tapes was Brad Wood, a local producer who played drums in the legendary Chicago band Shrimp Boat. He helped Phair create an album that any other producer would have screwed up. When they cut Exile in his studio, they kept it minimal. There was no back-up band — almost every sound came from Phair, Wood, and guitarist/engineer Casey Rice. The swirly, sparse sound of Exile is a sound that nobody else has ever figured out how to duplicate. “I feel like Brad gets a lot of credit for that,” she says. “He taught me a lot about minimalism.”

The music always centers on her wispy voice and off-kilter, free-form guitar. On “Fuck and Run” or “Mesmerizing,” there isn’t even a bass, to avoid crowding her out. Wood’s sonic template was the Young Marble Giants’ stripped-down 1980 UK postpunk cult classic Colossal Youth, as well as Spiritualized’s Laser Guided Melodies. Phair gets so much attention as a storyteller, people still underrate her as a guitar hero. “I think she’s getting more credit now,” Brad Wood told me. “It took a while, but I have always advocated for her genius on guitar. There is no one else that I’ve ever recorded in 30-plus years of doing this that approaches the guitar like she does. Her chord shapes have more to do with like, Glenn Branca than Joni Mitchell.”

Another crucial innovation of the sound: her flat Midwestern voice. “My poor mother, she just recently gave me singing lessons,” Phair admits. “I have such a nasal mumbly twang and there’s nothing to do about it now. It’s what everybody likes. But I hate hearing it.”

“I have a such a nasal mumbly twang and there’s nothing to about it now. It’s what everybody likes. But I hate hearing it.”

As soon as Exile dropped in the summer of 1993, it was instantly controversial. But as it grew into a cultural phenomenon, the backlash got nastier and more misogynistic. “I had not been assigned a chaperone,” Phair says. “I had not been assigned a manager. I had not been assigned a Svengali. I was unbound by male ownership, which was strange.” Guyville did not appreciate her input. “I was standing up against a lifetime’s worth of expectations, shouting into the wind on the edge of a cliff. In a way, that’s what I thought I was doing onstage, even though there were people there. ‘I’m here to shout into the wind. I’m going to try to ignore you, while I shout into the wind.’”

There’s a famous photo of Phair playing live, in her early days, taken by Marty Perez. She stands onstage in a Chicago rock club. The whole audience is a sea of frowning male faces. As soon as I mentioned this photo to Phair, she had a lot to say about it. “That was the wind I was shouting into. Those are the faces I saw every day. And every time I wanted to say something in the recording studio. Those are the faces I’m seeing every time I want to do something different with my career. Those are the faces I’m seeing every time I want to do anything or say anything. Those are the faces I see. It didn’t stop with Guyville. It wasn’t over. Once that record was finished, it was really just beginning. I’ve lived a whole career in those faces.”

But in 2023, Exile in Guyville is more acclaimed and beloved than ever. To Phair’s surprise, the album inspired a whole new generation of fans to start writing their own songs, from Soccer Mommy’s Sophie Allison to Speedy Ortiz’s Sadie Dupuis. For Snail Mail’s Lindsey Jordan, Phair was her first hero — in high school, she started a tribute band called “Lizard Phair.”

“I envy their confidence,” Phair admits. “I envy their sense of self. I always have, when I look at millennials and I look at Gen Z and I see the young female artists like me. They’re so complete. They have a real sense of autonomy that I didn’t have.”

“I remember when I first discovered that record,” Mannequin Pussy’s Marisa Dabice told me last year. “It just spoke so much to exactly where I was. It was one of those moments where you felt like someone had found your inner narrator and had put those emotions into songs. There’s certain things on this record I just had never heard a woman express before, outside the confines of my own head.”

Phair always hoped Exile would inspire other women to tell their stories. “This is the call to young girls who have the ability to compete,” she said in her first Rolling Stone feature in 1993. “Get out there and slug it out. There’s not enough female voices in popular culture. It’s a fucking crime.” She’s finally getting her wish.

Phair could have milked the Guyville formula forever, but she kept moving, making music that reflects every stage of her life. Whip-Smart is up there with Exile, with forever-underrated gems like “May Queen,” “Crater Lake,” and the title tune. Her 1998 Whitechocolatespacegg tends to speak to people coping with new parenthood, while her 2003 self-titled album speaks to people getting divorced. She wrote the memoir Horror Stories. She also reteamed with Wood to make her excellent 2021 Soberish, with the unrepentant theme song “Bad Kitty.” But Exile remains the center of her legend. It set a new standard for emotional courage and honesty that has stood ever since. That’s why Exile is an album that’s been making people feel less alone for 30 years.

Featured Image: Liz Phair performing at McCabe’s Guitar Store in Santa Monica, 1993. (Photo: Jeff Kravitz/FilmMagic, Inc.)