By Kay Hanley

Los Angeles Magazine, June 28, 2023

Ahhh… Cambridge, Massachusetts in the 1990s. Some people went there to attend very important institutions of higher learning. Or so I’ve heard. As for me? I migrated over the bridge from Boston to that mythical Gen X mecca several nights a week to pursue my education in the school of rock and roll, baby.

In the summer of 1993, I was waiting tables and tending bar at a restaurant in Cambridge called Michaela’s. I was so bad at this work that people would tell me to my face but the owner kept me around because I was friendly, cute, and had freakishly beautiful penmanship (thanks, Catholic school!), a skill which, once discovered, became coveted for addressing envelopes for invitations to Michaela’s many events. That’s a whole ‘nother story, obviously.

If the job was merely a placeholder, my whole reason for existing was to play and write songs with my band Letters To Cleo, and my obsessive hobbies were: seeing bands, discovering new bands, and seeking out a group of friends that facilitated nearly constant discussion of all of the above. In a town with college radio stations and local fanzines whose popularity and influence easily competed with that of Rolling Stone and our monster commercial radio stations WBCN and WFNX, the depth of my indie rock snob bullpen was subterranean. And then there was the all-knowing, benevolent Queen Snob, my starting pitcher of this analogy, Jules V.

Jules always had the early, arcane tapes, collected albums from all the obscure record labels in North Carolina or Idaho, befriended Dave Grohl at a Fugazi show in DC before Nirvana blew up (she was a “Bleach” fan), had an ongoing correspondence with late author David Foster Wallace, and, and, and … you get the picture. She was a human encyclopedia of cool shit and an enthusiastic sharer of underground music and arts knowledge. A lot of what Jules was into flew right over my head, to be honest. But her taste was unquestionable, and when she got giddy about something, it was tacitly understood that everyone in our social orbit was gonna check it out.

This is the backdrop for my introduction to Liz Phair’s astonishing debut album, Exile In Guyville 30 years ago this summer in Jules V’s 2nd floor apartment on Magazine Street in Central Square, Cambridge. And yes, this is an I-remember-exactly-where-I-was-when-that-happened story. Thus was the nature of the event, after all. Earth-shifting, page-turning, perspective-smashing, Exile In Guyville was a work of art that completely blew my mind at a time when I was free and open to having my mind blown.

A few of us had arrived sometime in the afternoon, each cradling a six-pack of beer in a paper bag crumpled by sweat from the half-mile walk to the Central Square T stop. Jules had just moved into the Magazine Street apartment and I remember it had a dormer in the living room with three enormous windows overlooking mature leafy trees that lined the street below. She had little more than a couch and a gleaming stereo system with a receiver, CD player, and a turntable (né record player). The latter not having made its nostalgic comeback yet, one didn’t see them around much in those days. We all took our places sitting mostly on the hardwood floor, drinking beers and talking over each other with the increasing volume of buzzed 24 year-olds who urgently need you to know what they know. Jules emerged from her bedroom and strode coolly down the hallway with a CD case in hand.

“Jon Bernhardt gave me this as a housewarming present.”

Jon was a DJ on WMBR, MIT’s very influential radio station whose broadcast signal had about the same wattage as a couple of lightbulbs. He was terrifying to me—his indie cred bonafides positively Albini-esque. As far as I knew, the only person who ever talked to him was Jules and I was sure that my being in a twee local alt-pop band made me unworthy of his notice. Jon had recently begun spinning tracks from Liz Phair’s new record and Jules was smitten.

We all nodded solemnly and prepared to listen.

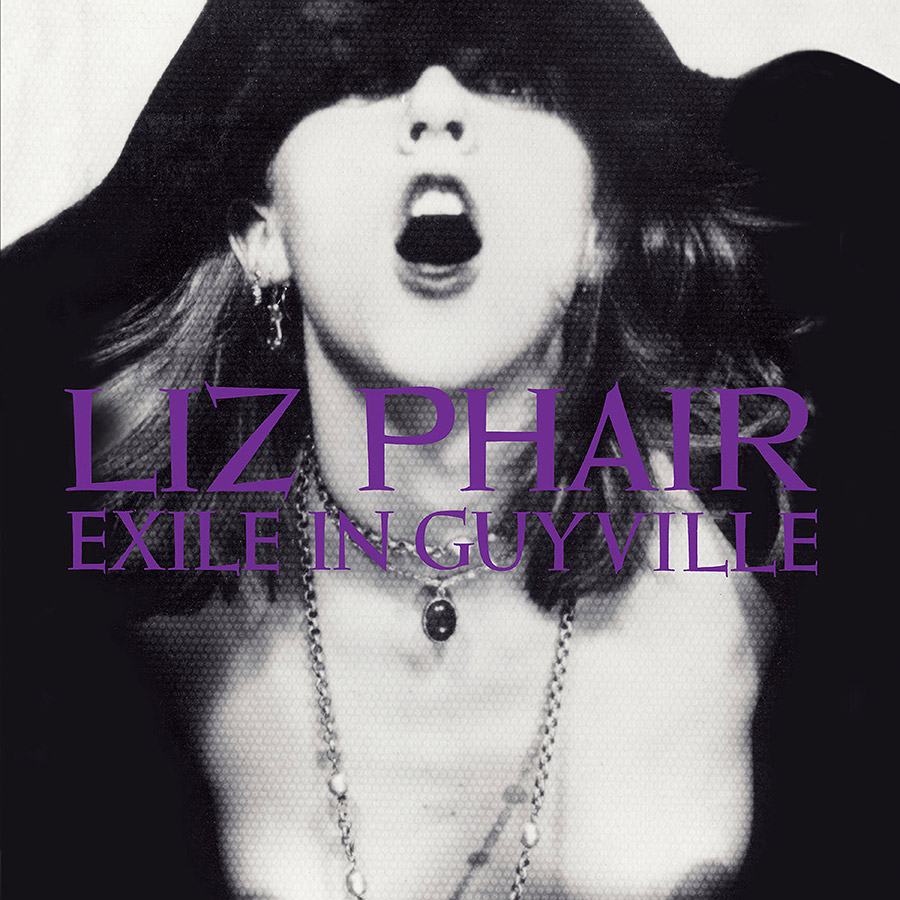

I swiped the empty jewel case from atop the stereo while Jules slid the CD into the player tray. I stared at the cover of Liz Phair’s Exile In Guyville featuring an inscrutable image of a hooded, open-mouthed girl. Was she screaming at someone? Giving a blowjob? Wait, is that her nipple? Do I like this or hate it? Both? The music oozed out of the speakers like spiked maple syrup. The voice was a woman’s but sung in a range that seemed very low, to the point where I wondered if she was uncomfortable singing that way.

“She was recording songs alone in her dorm room on a four-track and then Matador Records heard the tapes and signed her,” Jules said.

We were all very impressed by this.

The guitars and drums and vocals were all recorded in that warm, scratchy lo-fi way that was beloved by indie rock purists, but also sonically fresh and original. It was the sound of unedited contents from a person’s brain splattering out onto a reel of tape: horrifying true revelations about sex (both wanted and unwanted); jealousy; murder; loneliness.

The songs themselves were unconventional structures delivered with a disaffected phrasing that was meant to throw you off the fact that the melodies were pure confectioner’s sugar. The lyrics unspooled like storytelling, complete with characters and scenarios that seemed equal parts fabrication and way too personal. And it was obvious that Liz Phair, for reasons that I still don’t understand, possessed the brutal honesty to sing about stuff in a way that was absolutely off limits for men AND women in 1993 and she did not give a single flying fuck what you thought about that.

“I only ask because I’m a real cunt in spring / You can rent me by the hour”

“Fuck and run / Even when I was 17 / Fuck and run / Even when I was 12”

“And it’s true that I stole your lighter / And It’s also true that I lost the map / But when you said I wasn’t worth talking to I had to take your word on that”

The arrival of Liz Phair felt intoxicating. This was my initial opinion about Exile On Guyville, formed 30 years ago over the course of a few hours sitting on Jules’ living room floor on Magazine Street.

We all ran to Newbury Comics or Strawberries or Tower Records that week to buy the record and add Liz Phair’s name to the chatter. Within a few months, she was a famous rock star. It was one of the few instances when I was in genuine agreement with the grubby modern rock radio masses that a recording artist deserved respect and mainstream success. Exile In Guyville remains one of my favorite records and Liz one of the most fearless songwriters of my generation.

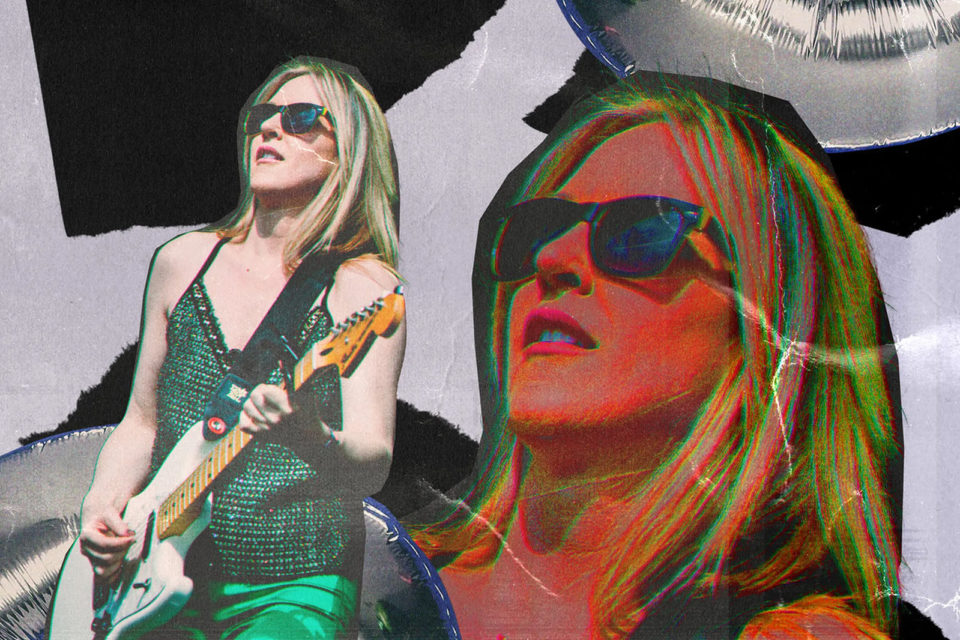

Liz and I played together at a Hot Stove Cool Music charity concert with the Cubs organization at Chicago’s legendary rock club, The Metro, in 2016. When I realized we’d be hanging out backstage, I agonized over what I’d say to her and how many fangirl details I should reveal. I needn’t have worried. When she appeared backstage, she walked right over and hugged me like we were old buddies. I thought maybe in the intervening 25 years since she first became a hero to me, I had also joined some kind of ’90s girl rocker sisterhood. At least, she made me feel like I knew the secret handshake. I sang “Never Said” with Liz on stage that night, chit-chatted with her and Eddie Vedder about baseball, and we exchanged numbers. I didn’t have a chance that night to tell her how much she and Exile In Guyville meant to me.

I still haven’t told her.

Kay Hanley is an Emmy- and Peabody Award-winning songwriter for TV animation, a music copyright advocate/activist with Songwriters of North America (SONA), and the singer of Boston-based rock band Letters To Cleo.

Featured Image: Liz Phair in 1998. (Photo: Paul Natkin / Getty Images)